How the Manhattan Project’s Nuclear Suburb Stayed Secret

Oak Ridge, Tennessee, once home to 75,000, went up fast and under the radar. But it was built to last, too.

Bill Wilcox was proud of his town. He’d been there since the beginning—before farmland gave way to dormitories and houses and lawns, before the ribbons of roads and sidewalks were laid down, before a single ball had rolled down a lane at the bowling alley. Before it even had a name.

When Wilcox arrived in this part of East Tennessee in 1943, soon after graduating from college with a degree in chemistry, he was among the first residents of the place that would eventually be called Oak Ridge. Wilcox lived and worked there for decades, and he later became the town’s historian. “Can’t image a better place to live,” he told an interviewer in 2013.

But Oak Ridge isn’t like most of the country’s other suburbs. The town was conceived and built by the United States government in the early 1940s as base for uranium and plutonium work, as part of the Manhattan Project. As the nuclear effort marched along, the town grew, too. By 1945, a dense suburb had taken shape, home to roughly 75,000 people. At war’s end, Oak Ridge was the fifth-largest city in the state—and all along, it was supposed to be a secret.

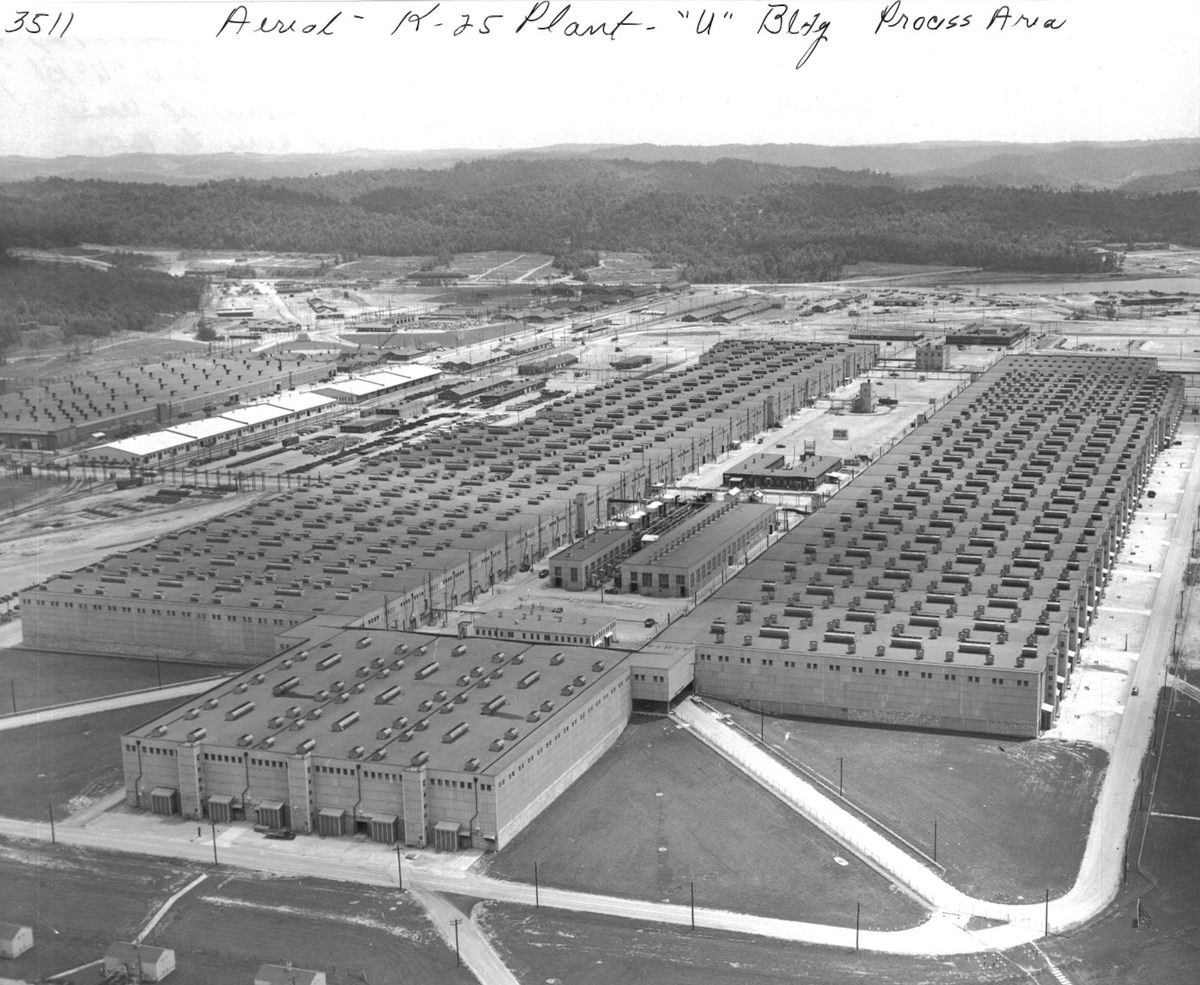

A government in search of a site for a secret enclave could do worse than Oak Ridge. The Clinch River ran nearby, local topography provided a natural buffer, and East Tennessee offered an abundance of electrical power for engineers, since it had just been electrified by the New Deal. The location, roughly 20 miles from Knoxville, was relatively remote, and close to train lines without being right on top of them. Before the federal government acquired 59,000 acres, the existing town, such as it was, consisted mostly of a patchwork of farmland nestled in valleys. By scattering work sites, the engineers reasoned, they could hedge their bets against catastrophe. If something went terribly wrong at one site, perhaps the hills could contain a fire or explosion.

In 1942, under the instructions of Leslie R. Groves, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers officer directing the Manhattan Project, the government approached the families that lived there—some of whom had owned their farmsteads for generations—and “summarily evicted” them, says Martin Moeller Jr., senior curator at the National Building Museum and organizer of the new exhibition Secret Cities: The Architecture and Planning of the Manhattan Project. A few people filed lawsuits, but by and large, Moeller says, the plan worked. Moeller chalks this up to one of the ruses the organizers devised: They described the project as a “demolition range,” so any possible holdouts could be scared off with the threat of near-constant explosions. The lie was “a relatively successful one that people didn’t question,” Moeller says—after all, how could they have even imagined what the government had in mind? “That generally got people the hell out.”

By the time Wilcox arrived, in October 1943, things were humming along. “It was farmland, you could tell that, but there was construction going on everywhere you looked,” he recalled. His first day left a crick in his neck, he remembered, “from shaking my head all day long.” Streams of trucks and people, the clanging and banging of tools, a smattering of signs that looked, to the uninitiated, like cryptograms. The roads weren’t yet paved, and plank boardwalks stood in for sidewalks. For a little while at least.

The town scaled up fast. The laboratories took up most of the space, but rather than constructing basic dormitories for employees, the architects and designers settled on a suburban vision, a cluster of single family homes on a part of the property about one mile wide and six miles long. “It was considered vital that these very sophisticated scientists and engineers should feel very comfortable right way,” Moeller says. Their work—including producing enriched uranium—was difficult, he adds, and it was determined that “they should have all of the comforts of a real town in order to work as effectively as possible.”

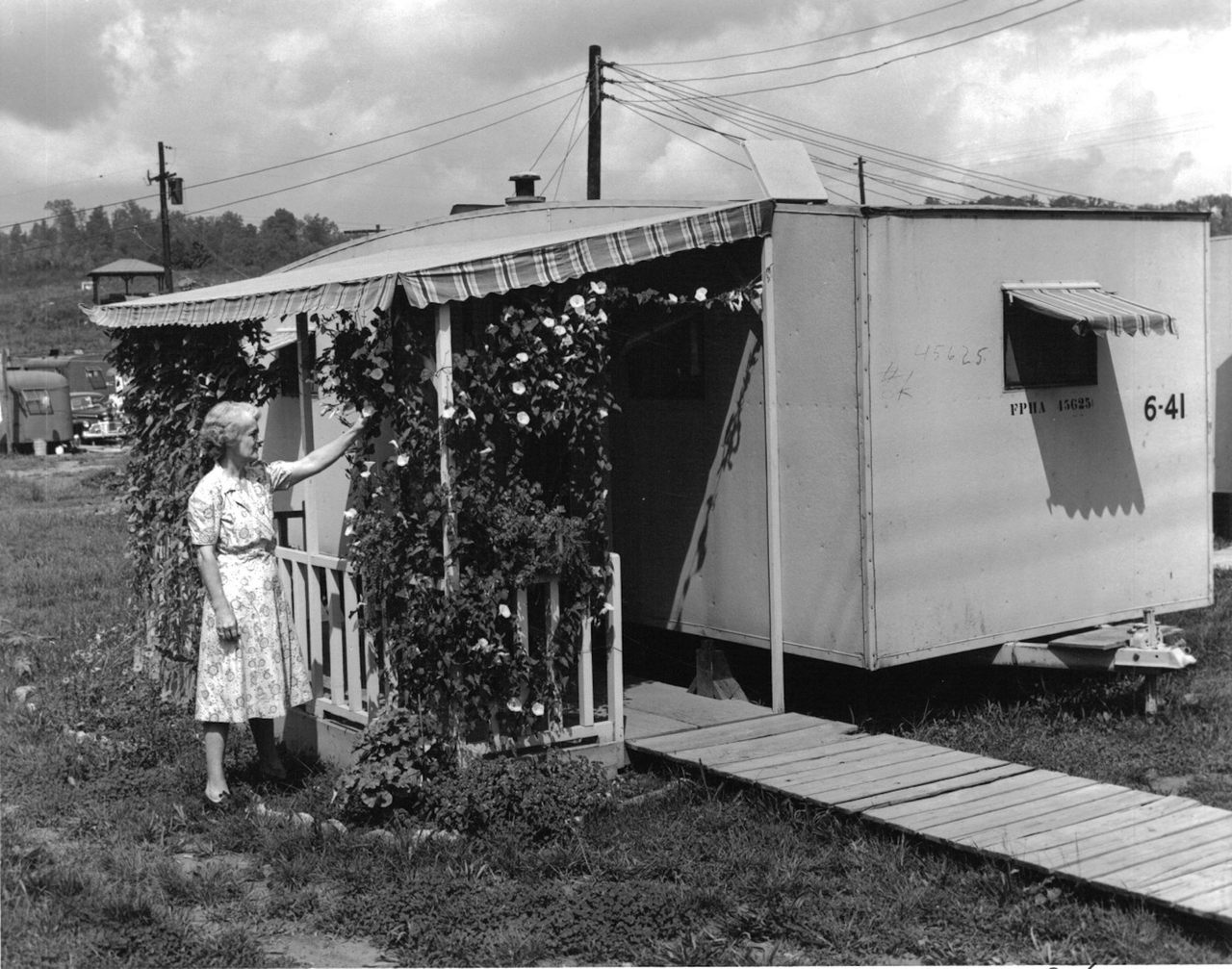

To pull this off quickly and without attracting too much attention, the architects relied on prefabricated and semi-prefabricated housing. In some cases, a house might come in two halves, on the back of a truck, to be assembled on-site. Oak Ridge also included many “cemesto houses,” made from panels of cement and asbestos. These were also called “alphabet houses,” because of the way their various iterations were named. (“A” houses were fairly modest, for instance, while “D” houses included dining rooms.) Housing choice was generally associated with seniority, though allowances were sometimes made for large families. None of these dwellings were exactly luxurious, but—even at the height of anxiety about the demise of Western civilization, Moeller says—architects were prioritizing “nice, basic, comfortable American suburban houses.”

At least for some. While white employees lived in relatively cushy digs, their black counterparts were more likely to be placed in structures known as “hutments,” little more than plywood frames without indoor plumbing. “Segregation was actually designed in from the start,” Moeller says.

The demand for new homes continued to boom, and people were temporarily housed in apartments, dorms, and trailers. At the height of the building frenzy, a contractor turned over the keys to a new home every 30 minutes.

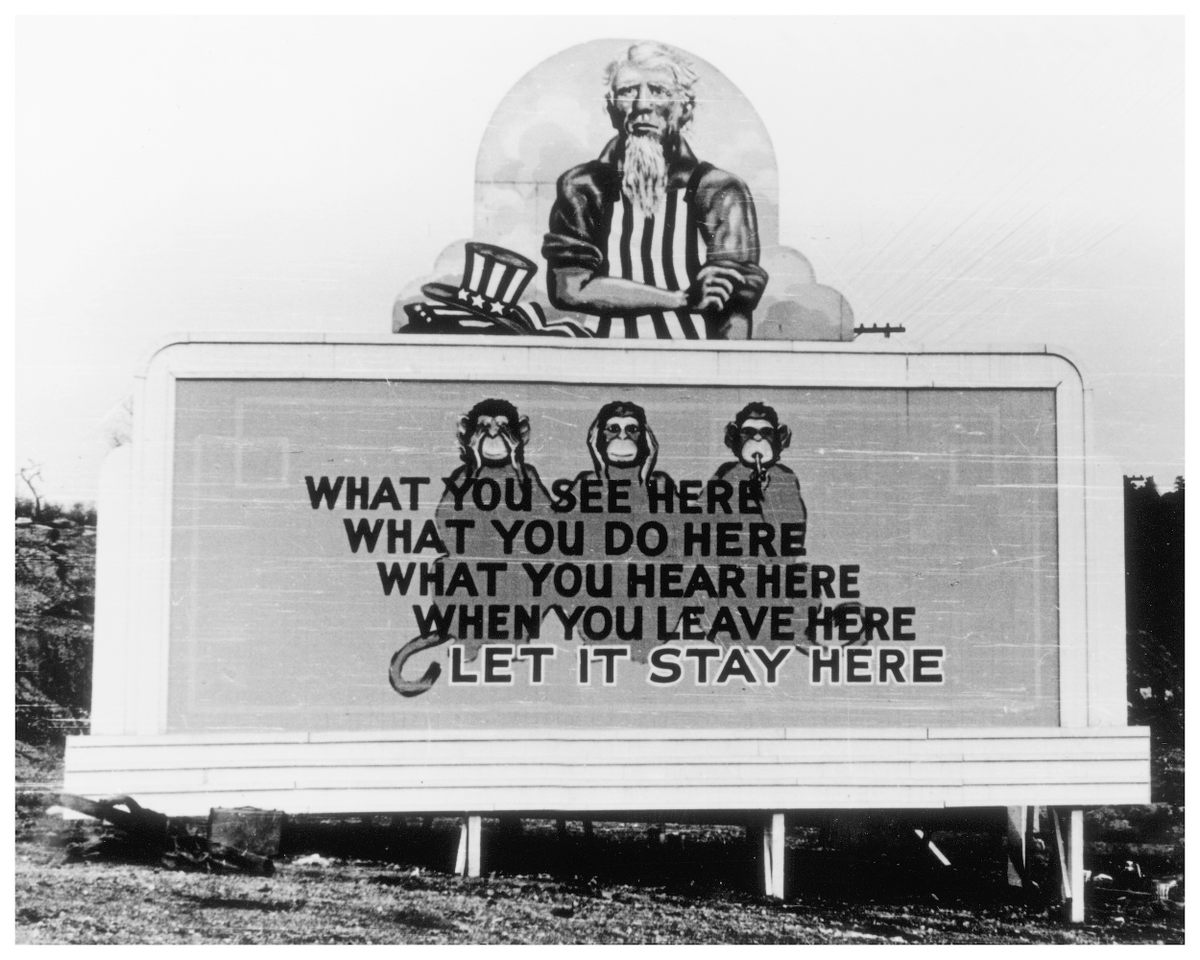

The pace of building there was stunning enough, but doing it all under the radar required a little willful blindness. The town didn’t appear on any official maps, and visitors were screened by guards posted at the entrances. Still, at that scale, it couldn’t be truly clandestine. “People saw stuff, certainly,” Moeller says, but probably chose not to wonder too deeply about what was happening there out of a combination of patriotism and ignorance. Moeller speculates that those who saw workers and supplies streaming into the site may have sensed that asking too many questions would have been un-American. The idea was, “it’s not my business; it’s for the war effort,” he says. “There was a much greater spirit of national unity than we could even fathom now.”

Billboards were installed all over town to remind workers to keep their mouths shut about their work, even though most workers knew very little about the project’s true scope. Even if a loose-lipped employee had divulged minor things, Moeller adds, “it would really take a lot of details to add up to the full picture.” The general public was familiar with the concepts of X-rays and radioactivity, but the bomb and its potential would have been mind-boggling. “No one could imagine that you could make this superbomb using these tiny amounts of material,” Moeller says.

Similar “secret cities” were built in other parts of the country, such as Los Alamos, New Mexico, and Hanford, Washington, home to 125,000. Designers of these towns had additional tactics to obscure specifics. In Los Alamos and Hanford, sometimes everyone was given the same mailing address. At Oak Ridge, street addresses were designed to be confusing to outsiders. Bus routes might be called X-10 or K-25 or Y-12, in reference to the factories they led to, while dorms had simple names such as M1, M2, and M3. If you didn’t already know where you were trying to go, none of it would make sense. “There weren’t any signs on buildings, just numbers, codes names, and numbers,” Wilcox recalled. The town was full of such ciphers, and even employees didn’t know how to decode them all.

Oak Ridge is no secret anymore. Its streets opened to the public in 1949. The Atomic Energy Commission helped get a city council off the ground, and the town incorporated a decade later. Now, it shows up on maps and census records (29,000 people) just like any other American town. But even today, with no secrecy at all, the Department of Energy remains the main employer, and in 2012, a gaggle of peace activists—including an elderly nun—breached and vandalized a facility there that stores some of the most dangerous nuclear material in the world.

For all the speed with which they went up, many of Oak Ridge’s homes turned out to be built to last. Drive around the east end of town today and you’ll see many cemesto houses still standing, says Ray Smith, who became the town historian around three years ago, after Wilcox passed away. When the town was incorporated, he says, many of the homes were sold to the people who had, up to that point, been renting them from the government. They may have been transformed with a little new brickwork or siding, but the old alphabet system is alive and well. “Oak Ridgers can say, ‘Oh, that’s a ‘B’ house. My grandmother lives in a ‘D’ house,’” Moeller says. “They don’t think anything is unusual about that.”

Those intimidating billboards about betraying your country with loose lips are long gone, and the town now proudly broadcasts its past. One of its major summer events is the Secret City Festival—a weekend of parades, concerts, and tours of the federal facilities. “It’s the only time during the year that the public can gain access,” Smith says. Some secrets continue to fascinate, even when they’re out in the open.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook