The Chef Cooking a Cicada Recipe for Every Palate

From ceviche to caramel popcorn, Joseph Yoon is showing how Brood X can be a delicious part of your diet.

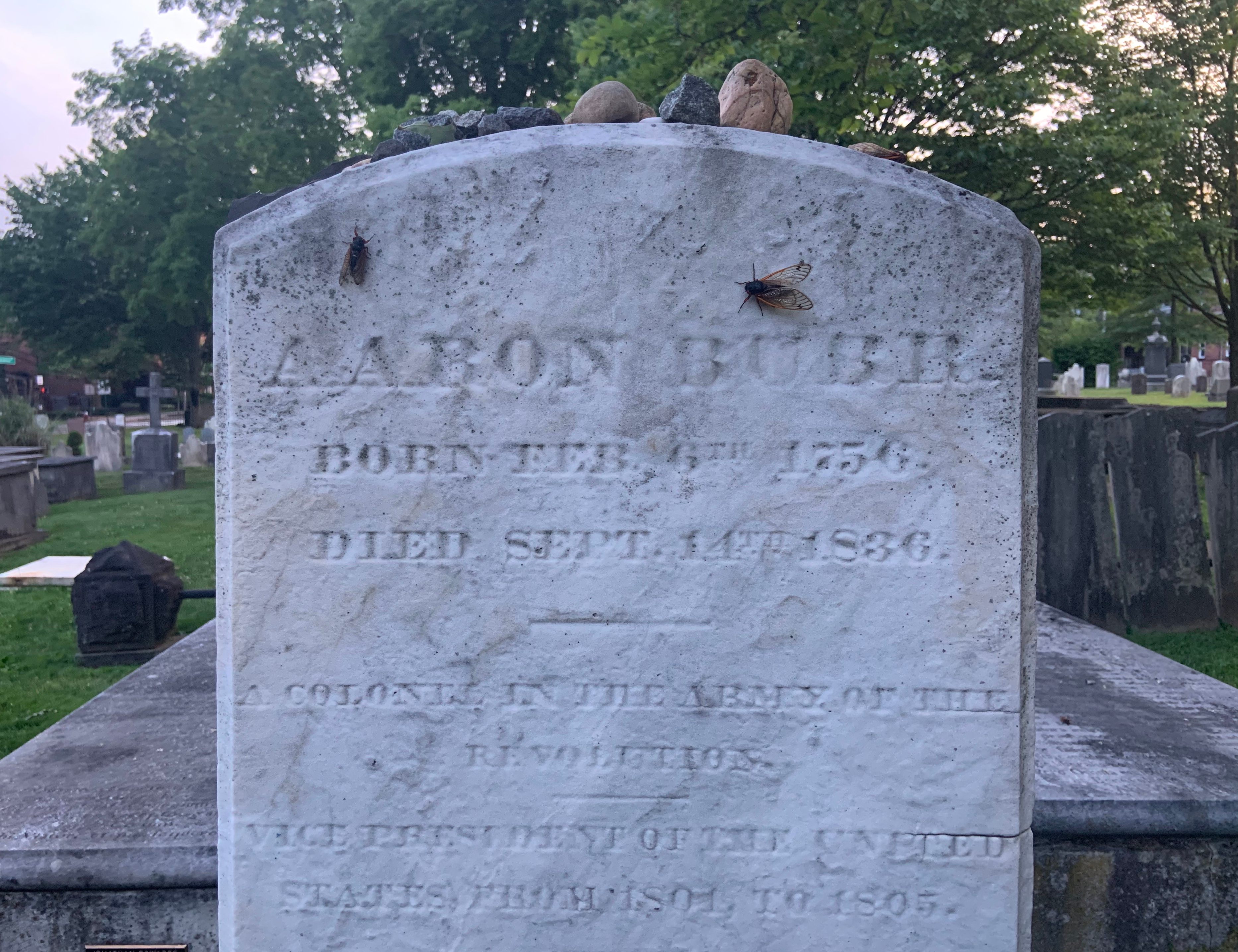

The sun is setting in Princeton, New Jersey, and Joseph Yoon is plucking cicadas off the grave of Aaron Burr. Princeton Cemetery is the final resting place of the infamous politician who killed Alexander Hamilton. This May and June, it’s also been home to a group of Brood X cicadas. On this night, cicada nymphs crawl across 18th-century stone engravings, adults flutter from grave to grave, and empty, molted shells crunch underfoot. The cemetery is an apt location for the group: After living for 17 years underground as nymphs, Brood X cicadas emerge for a mere few weeks to mature, mate, lay eggs, and die.

During this brief window, Yoon is on a mission to collect cicadas across their life stages. The insects’ destination? His kitchen. A professional chef, Yoon is a passionate advocate for incorporating insects into one’s diet. His company, Brooklyn Bugs, has provided insect feasts for museums, universities, and private events, with everything from tarantulas to grasshoppers to tobacco hornworms on the menu. He views Brood X, which appears in massively high numbers estimated at up to 1.4 million per acre in hotspots, as an exciting opportunity to show the breadth of insect-based cuisine.

Over the past few weeks, Yoon’s Brooklyn apartment has been transformed into something of an edible-insect lab. (His freezer is so packed with cicadas that he secured a separate storage freezer for the rest.) When he’s not shuttling back and forth from Princeton to collect samples, he is experimenting with different preparations, ranging from fermenting to baking to coating in chocolate and gold leaf.

“It’s all about seeing the flavor profiles and trying to unlock the functionality of the cicadas,” he says. “I want to open the doors as much as possible.”

Yoon is focusing on Princeton because it’s the closest cicada hotspot to his home in New York, but the three species within Brood X appear across the Eastern United States in their stunningly coordinated 17-year cycle. These cicadas go through four major life phases: eggs, nymphs, tenerals (a brief stage that follows molting), and adults. Each phase offers a different texture and flavor, and Yoon’s various preparations play upon these distinct characteristics.

Since the eggs of this generation of Brood X hatched 17 years ago, Yoon started his quest with the nymph phase, harvesting large batches in early and mid May. (Some Princeton University students might notice Yoon in the background of their graduation photos, crouched in the dirt with a trowel and a takeout container of writhing insects.) Halved, the nymphs reveal a surprisingly meaty, white interior. After eating one that was simply blanched, I thought it resembled what a tofu-filled M&M might taste like, with its crisp shell giving way to a spongy, earthy interior.

“The meatiness of the nymphs has been such a revelation to me,” Yoon says. “There’s so much bite and chew to these insects.”

Yoon has experimented with a variety of nymph recipes across the flavor spectrum. On the sweet side, he’s prepared a chocolate-caramel peanut popcorn, in which the nymphs’ M&M-like texture blends perfectly with the crunchiness of the popcorn and nuts. On the sour end, he’s prepared several batches of nymph kimchi—a favorite dish for Yoon, who is of Korean descent. “If you think about traditional kimchi, you have brined shrimp or some element that has that sense of umami flavor you look for in kimchi, that brininess,” he says. “The cicada nymphs look like little baby shrimp when they’re covered in the kimchi paste. When I bite into them, they explode full of flavor.”

For Yoon, it isn’t so much about cicada haute cuisine, but about creating dishes that people will actually eat. “When people ask me, ‘What should I do with my cicadas?’ I ask them, ‘What do you like to eat?’ It’s important to work them into dishes you normally enjoy.”

Jessica Ware, an entomologist and curator at the American Museum of Natural History, agrees that simplicity is key. “Some people worry cicadas are going to taste bad and put effort into masking their flavor, but the flavor itself is very good, very nutty and delicious,” she says, referring to adult cicadas. “The same way you’d add mushroom or beef or seitan to a dish, you could add insects.”

Ware notes that American reactions to periodical cicadas like Brood X are as predictably cyclical as the cicadas themselves. “There’s this anthropology surrounding cicadas and people being both frightened that they’re a plague and excited that so many are coming,” she says. “There’s a thread of people getting freaked out and excited every 17 years.”

In his book, Periodical Cicadas: The Brood X Edition, entomologist Gene Kritsky traces this thread of excitement and freak-outs over 300 years. While the earliest recorded sighting of cicadas in the United States comes from the 1630s, the first record of Brood X specifically comes from Philadelphia, in 1715. (Though these are the earliest known written records, Indigenous communities undoubtedly observed cicadas earlier than this.) The Philadelphia reverend observed that “swine and poultry ate them but what was more astonishing, when they first appeared some of the people split them open and eat [sic] them.”

Later, in 1885, a scientist took a more cheeky approach: In an article titled “Fried Locusts for Breakfast” (cicadas were erroneously identified as locusts for many years), entomologist Charles V. Riley offered a visitor “a spoonful of dark brown objects, like very small fried oysters,” telling his guest, “Don’t be afraid of them. They are only the quintessence of vegetable juices, and everything in nature feeds upon them ravenously.” To Riley, the cicadas were a “rare tidbit” that “might rank with frogs’ legs, birds’ nests, shad roes, and whitebait.”

But eaters didn’t always eat cicadas as a fun experiment. Sometimes they did so out of desperation. In 1779, after George Washington destroyed the Onondaga Nation’s crops in what is now New York, they were forced to eat that year’s periodic cicadas (a different group from Brood X). Today, members of the Onondaga Nation still eat cicadas as a tribute to their ancestors’ triumph over hardship.

Yoon’s quest is somewhere in the middle of Riley’s quirky antics and the serious survival mission of the Onondaga people. He makes for a jolly ambassador, spreading the word on the joys of edible insects, with a smile on his face and a kazoo in his pocket—just in case he wants to jam with the chorusing cicadas. But he is completely serious about the importance of changing the way we eat and produce food. Insects like cicadas are packed with protein, providing a sustainable alternative to foods such as red meat. Insect farms require a mere fraction of the resources devoted to cow farms, and cows also produce methane, a greenhouse gas.

Many cultures have been eating insects for millennia, so snacks such as Mexican ant larvae, Namibian mopane worms, or Japanese wasp crackers are commonplace. But the dangers of climate change have led some chefs in white and Eurocentric cultures to start playing culinary catch-up: In Washington DC, Spanish chef José Andrés has made chapulines (grasshopper) tacos. In Denmark, René Redzepi is a vocal advocate for edible insects, frequently serving ants at his Copenhagen restaurant, Noma. And most recently, James Beard winner Bun Lai has added Brood X cicadas to his menu in Connecticut.

“And still, this isn’t enough,” Yoon says. “We need to move the needle more. It’s more than one chef, one product, one recipe.”

Cue Yoon’s quest to make up to 100 cicada recipes. In addition to the nymphs, he’s also working with the tender, just-molted tenerals. This is the most spectacular, and brief, of the cicada phases: After the nymph climbs onto a branch or tree trunk, it slowly breaks through its skin, revealing a new, ghostly white exoskeleton. In the cemetery, several tenerals are slowly unfurling on old headstones. A favorite among many entomologists who eat cicadas, the teneral is both tender and nicely nutty. Since the window for harvesting these is short (they quickly transform into darkened adults, sometimes before you have time to bring them home), Yoon has prepared only one dish with them: a refreshing, spicy ceviche.

As this generation of Brood X wraps up its lifetime and disappears over the next few weeks, Yoon is gathering the samples he can and starting to dig in with his recipe experiments. So far, the winged, black adults have added their meaty, earthy, delicate crunch to stuffed shells (with ricotta and herbs) and a savory Spanish tortilla. One picky eater who’s not quite as excited about Yoon’s quest is his pet tarantula, Natasha. The chef tried to give her a cicada, but Natasha refused, preferring her usual crickets. “Natasha is not an adventurous eater,” Yoon laughs. If you want to be more adventurous than a Brooklyn-dwelling tarantula, here are a few of Yoon’s recipes and tips for harvesting, cleaning, and feasting on cicadas at their various life phases.

A Guide to Collecting and Cooking Cicadas

Here are a few of the recipes Yoon has devised with Brood X so far. You can find others, such as his nymph ramp kimchi, on his Instagram account. The first step to harvesting cicadas is to find out if they’re near you. Use an app such as Cicada Safari, which helpfully maps the Brood’s appearances. Once you find a good cicada spot, make sure to do some quality control as you collect. It’s important to look for any signs of illness, especially a white fungus on their bottoms, and to clean your cicadas before eating (some further instructions on that below). Finally, be as compassionate as you can in your method of euthanizing them: Yoon freezes his cicadas (methods like suffocation take a cruel amount of time).

While Brood X does appear in massively high numbers, Ware also cautions against citizen-scientists over-collecting. She’s noted that the cicadas have appeared in a surprisingly patchy pattern in some areas and, to avoid disrupting their distribution any further, she recommends harvesting those that are healthy but damaged in other ways (such as broken wings or legs).

Note: If you have any kind of seafood or shellfish allergy, please check with your doctor before eating cicadas.

Nymph Caramel-Chocolate Popcorn

Ingredients

1 cup cicada nymphs

½ cup popcorn kernels

2 tablespoons olive oil

1/2 stick unsalted butter, plus extra for drizzling over popcorn

1 1/4 cup brown sugar

1/4 cup light corn syrup

2 teaspoons vanilla extract

1/4 teaspoon baking soda

1 cup peanuts

1 cup bittersweet chocolate chips (I used Valrhona Guanaja chocolate)

Salt, to taste

Instructions

1. If you’ve just harvested your nymphs, be sure to wash them before freezing. After you’ve frozen them overnight, blanch the pre-washed nymphs for 30 seconds, then set aside to dry.

2. Add the popcorn kernels and olive oil to a large saucepan over medium heat, and make sure you cover each kernel with oil. Once the kernels have fully popped, transfer to a bowl and drizzle with the melted butter and some salt.

3. In a separate pot, add the butter, brown sugar, and corn syrup. Cook over medium-low heat, stirring frequently. Turn the heat to high when the mixture is fully incorporated and let it boil to 255 degrees F (or for a few minutes), then add the vanilla and the baking soda. Be careful as it will bubble and expand from the baking soda. Stir everything together, and add the nymphs and peanuts and mix in.

4. Pour the caramel-nymph mixture over the popcorn and stir to coat everything evenly. Spread everything over a parchment-lined baking sheet, then place in a 225- to 250-degree F oven for 60 to 90 mins, or until it dries out.

5. In a double-boiler, melt the chocolate pieces over medium heat.

6. Remove the popcorn from the oven and drizzle with the chocolate. Let it cool completely, and enjoy.

Nymph Edamame

Ingredients

1 package of edamame

1 tablespoon olive oil

3 cloves garlic

½ cup cicada nymphs

1 teaspoon wasabi furikake

Pinch of salt

Pinch of pepper

1 teaspoon Maldon sea salt (or kosher salt)

Instructions

1. If you’ve just harvested your nymphs, be sure to wash them before freezing. After you’ve frozen them overnight, blanch the pre-washed nymphs for 30 seconds, then set aside to dry.

2. Boil or steam the edamame according to the package instructions. Drain and set aside in a bowl.

3. Slice garlic into thin chips. Add 1 tablespoon of oil in a preheated frying pan over medium heat, then add the garlic chips, frying until they start to turn brown at the edges. Flip the garlic over to fry on the other side, and add the nymphs, salt, and pepper. Once the other side has browned, remove everything from the heat and add directly to the bowl of edamame.

4. Liberally top the entire bowl with the furikake and quality sea salt (I used Maldon sea salt but kosher salt works well too).

Teneral Ceviche

Ingredients

½ gochu (Korean pepper), thinly sliced

½ chili pepper, thinly sliced

½ cup enoki mushrooms

2 tablespoons shallots, thinly sliced

1 tablespoon garlic slivers

2 parts lime juice to 1 part lemon juice

2 parts salt, 1 part pepper, 1/2 part cumin

Instructions

1. Gently rinse your tenerals in a bowl of cold water. Do not boil your tenerals. They are too tender and the insides will melt.

2. Combine all the ingredients except the juices in a small bowl. Pour the juices over everything and gently mix. Cover, and set in the fridge for a minimum of two hours, or overnight.

3. Remove from the fridge and enjoy on its own, on tortilla chips, or with lettuce rice cups.

Note: It may be difficult to collect tenerals, so you can also do this recipe with the nymphs and adults.

Spanish Tortilla With Adult Cicadas

Ingredients

4 tablespoons olive oil

1/2 cup adult cicadas, wings removed if you prefer

1 medium potato, chopped into ½-inch-thick wedges

1/2 red pepper, diced

1 small onion, diced

4 large organic eggs

1/3 cup chopped parsley

2 to 3 cloves garlic, minced or sliced

Salt and pepper

Instructions

1. If you’ve just harvested the cicadas, place them in the freezer overnight. When you’re ready to cook them, remove the wings from the adult cicadas, rinse, and set aside.

2. Boil the potato wedges in a small pot until tender, then drain and set aside. (Traditionally you fry the potatoes in a ton of oil for a Spanish tortilla, but I’m trying to eat healthier, so I boil my potatoes instead.)

3. Add two tablespoons of oil in a preheated saucepan over medium high heat, then add onions, peppers, garlic, salt, and pepper. Add the cicadas when the veggies begin to become translucent. Cook until the onions start to slightly brown.

4. Beat the eggs in a large bowl with a pinch each of salt and pepper, then add the potatoes, the sauteed ingredients, and the parsley. Gently stir everything together—it’s okay if the eggs start to cook slightly from the hot potatoes (they’re going in the pan, after all).

5. In a non-stick skillet that’s been preheated over medium to medium-high heat, add two tablespoons of olive oil. Pour everything into the skillet and gently push the edges of the eggs toward the center to let the runny portion come to the edges and cook evenly. Then lower the heat to medium, and cook until the eggs begin to set (5 minutes or so).

6. Shake the pan around to make sure the tortilla isn’t sticking to the pan. Most of it should be cooked through, with the top still a little runny. Put a pan lid that’s larger than the frying pan on top, and flip the tortilla over. Add a little more oil to the frying pan, then slide the tortilla back into it (the uncooked side will be on the bottom now).

7. It should take only a few more minutes for it to cook through. You can use a toothpick to check for doneness. Flip or slide the tortilla onto a plate and let it cool slightly before cutting to serve. You can serve this cut into bite sized squares or as pie wedges. Serve it with a side of aioli, spicy aioli, mayo, or just as is.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook