The Forgotten Baking Technique That Turns Bacteria Into Delicious, Cheesy Bread

Making salt-rising bread is a culinary science experiment dating back to the 1800s.

Update: Six years after I last wrote about salt-rising bread, I finally made it myself. With the recent explosion in home baking, it’s the perfect time to capture some wild microbes and release them onto our plates. If you’d like to make salt-rising bread on your own, read on to the end, where I’ve added a recipe and tips from a recent conversation with Susan and Jenny.

Its flavor is often described as “cheese-like,” its crumb dense, and its odor memorable. Salt-rising bread is special to those who remember it as a home-cooked comfort by a grandmother or parent. It’s also one of the only breads that uses a mix of bacteria, rather than yeast, to rise—a mix that includes a form of Clostridium perfringens, the culprit commonly known to cause the discomforts of food poisoning and the purulent wounds of gangrene.

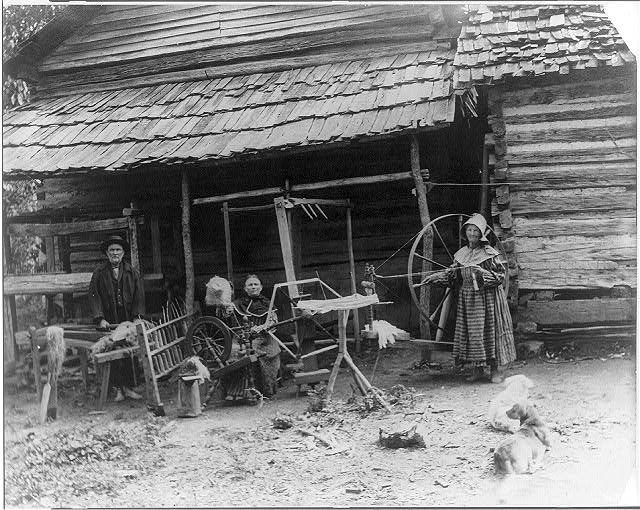

No one exactly knows where salt-rising bread originated, but the prevailing idea is that pioneer women developed the recipe as they traveled along the Appalachian mountain range, where the bread is most often found today. Before the 1860s, commercial yeast didn’t exist; most breads were leavened through sourdough starters, or by skimming the yeast and bacterial byproducts from the beer-making process, neither of which were available in pioneer life. Salt-rising bread doesn’t need yeast to rise, and contrary to its name, the bread doesn’t really need salt. (Some say it may have earned its name from the rock salt pioneers used to regulate the temperature of the starter dough.)

Salt-rising bread’s pungent, sharp smell is either loved or hated, and sometimes compared to dirty socks, with a unique cheesy taste that aficionados love. After its invention the bread became incredibly popular, with recipes for it appearing in many cookbooks into the 1920s; it even played a central role in the Kansas governor’s race in 1910. Even in 2012, Country magazine called salt-rising bread its “all-time most requested recipe.”

Glenda Riley writes in The Annals of Iowa journal that the meals of one pioneer “regularly featured … salt-rising bread, which she worked at in between her other chores,” starting the bread as they made afternoon camp, letting it rise until midnight by the fire, and having the dough rise again until it was ready to bake at breakfast time, ever with a watchful eye making sure the dough was rising properly.

If you think this sounds time-consuming and difficult, you would be correct. In Beard on Bread, James Beard notes that salt-rising bread is “unpredictable,” adding that, “You may try the same recipe three or four times and find that it works the fifth time…you may be disappointed.” If you Google salt-rising bread, one of the first results is an allrecipes.com entry that warns in the shouting tone of all caps: “THIS IS NOT AN EASY BREAD TO MAKE!”

In the early 20th century, this lengthy, yeast-less process also became an interest of microbiologists. In 1914, Richard N. Hart noted in his book Leavening Agents that salt-rising bread “seems to fail in a well-sterilized room,” and alludes to the experiments of Henry A. Kohman, who discovered that salt-rising dough lacked yeast completely “but literally swarmed with bacteria.”

In 1910, Kohman was funded by the aforementioned bread-obsessed Kansas Governor, Walter R. Stubbs, to learn how bakers could reliably make it, and concluded that a variety of anaerobic bacteria allowed the bread to rise. In 1923, microbiologist Stuart A. Koser began to suspect the mix might include bacteria found in human intestines and wounds.

To explore his hypothesis, Koser started with a few experiments that exposed guinea pigs to the bacteria, and confirmed that innocuous Bacillus welchii (now called C. perfringens) spores were present in the bread, but his experiments quickly dove into the macabre. He decided to take it a step further and bake a loaf of his own using the toxic bacteria from a soldier’s gangrenous wound.

Koser made a salt-rising bread starter in his lab, and successfully created the grossest, and possibly the most dangerous bread in history. The wound bacteria–made bread that did not go over so well with the guinea pigs this time around.

It seems that practically anything can capture the right bacteria to make salt-rising bread. A man named Reinald Neilsen conducted dozens of baking experiments using different salt-rising bread starters. In 2002, he published an article in Petits Propos Culinaires on how he successfully made salt-rising bread starters out of oats, cheese, and even tree bark, which apparently works well, but needs to be picked out of the bread as it’s eaten.

The diverse range of salt-rising bread starters is possible because of the bacteria they attract. Salt-rising bread bakers create a fruitful environment for bacteria using a process called alkaline fermentation. Boiling water or milk is poured over a base like cornmeal or potatoes. It is left to sit for hours between 90 and 110 degrees Fahrenheit before flour is added and it sits again. This captures a medley of wild bacteria including Bacillus, C. perfringens, and Lactobacillus, which feed from each other in a symbiotic relationship visible in the bubbling, foaming mixture that forms, called the sponge. After nine to 12 hours of bacterial growth, it’s ready to bake.

Typically, this sounds like the opposite of what one wants to do with food. The dangerous strains of the C. perfringens bacteria are what keep us from eating old meat and the nightmare that keeps restaurants in a constant state of concern about food temperatures. So how have generations of Appalachian cooks been eating this bread, which hasn’t produced a single case of food poisoning?

The truth is, the strain of bacteria in salt-rising bread is completely safe—though the reasons why are slightly mysterious. Jenny Bardwell and Susan Brown, professional bakers who have researched how salt-rising bread works for more than 20 years, collaborated with microbiologists to test it. The resulting paper, “The Microbiology of Salt Rising Bread,” published in the West Virginia Medical Journal, notes that the bread does contain this bacteria, but testing indicates the strain is “unable to cause C. perfringens type A food poisoning.”

The reason this strain exists may lie in bacteria’s ability to change. In certain environments, bacteria may find a mini-evolutionary advantage to gaining or losing genetic traits–including traits that involve giving off toxins. The environment of a wound, in contrast to that of bread dough, might attract and cultivate very different strains of the same bacteria. Even if toxic strains of C. perfringens make it into the bread, study coauthor Gregory Juckett notes that baking temperatures are far above tolerance levels for the bacteria.

Since salt-rising bread has so far been known as a niche food item, there has been little funding to study it, but there have been studies with other breads using bacterial fermentation. In Greece, a similar bread uses chickpeas; in Sudan, another calls for lentils. Preparations of both items indicate that the result is like that of salt-rising bread. Kenkey, a dumpling-like bread from Ghana made of a corn-based fermented dough, may also use a related process.

Not everyone has the drive to experiment, however, and the time needed to make salt-rising bread is what eventually caused it to recede into obscurity. By 1920, the Manual of Homemaking had labeled salt-rising bread, “An old-fashioned bread, the making of which is almost a lost art to-day.”

Bardwell and Brown explain in The Handbook of Indigenous Alkaline Fermentation that by the mid-1900s, salt-rising bread was available in bakeries, with fewer people baking it at home. When production of commercial salt-rising bread starters ceased in the 1960s, most people stopped making it. Today salt-rising bread is usually sought because of nostalgia, the memory of lost family members and home-cooked meals; Bardwell and Brown’s own personal ties to the bread go back generations, and are part of what inspired their research in the first place.

“There are memories that tastes provoke and smells provoke–and salt-rising bread has a very strong smell,” says Brown. “People will come into the bakery, take a loaf, put it up to their face and take a really long, deep breath.” At Rising Creek Bakery in Mt. Morris, Pennsylvania, Bardwell and Brown spent years baking salt-rising bread. They show anyone who will listen how to make it and encourage scientists to study it, believing that salt-rising bread may even further teach microbiologists how probiotics keep us healthy.

“Susan and I have many responses from people saying that salt-rising bread calms their stomachs and is soothing to them when they can’t eat anything else,” says Bardwell. “Salt-rising bread may even be some kind of cure that helps people.” This might make sense: C. perfringens and Lactobacillus are, after all, both present in the human digestive system. Amid studies about intestinal flora and a constant stream of probiotics on grocery shelves, studying and eating this unlikely food may hold more benefits than its pioneer inventors knew.

How to Make Salt-Rising Bread

Traditional salt-rising bread (SRB) recipes are usually simple, a call-back to their roots as a bread born of scarce ingredients. I used Susan’s grandmother’s recipe, which makes a bread with a dense, somewhat dry crumb, perfect when toasted with salted butter. But there are many more recipes to choose from, including those on Susan’s website.

Although they’ve both retired from the bakery, Susan and Jenny guided me through the home baking process and gave their best tips on how to make a good loaf.

Their specific advice is in the recipe below, but overall, they emphasize that the trick to making salt-rising bread is embracing its unpredictability. Since the recipe uses wild microbes, which are not predictable like store-bought yeast, it’s a lesson in mindfulness and patience. You have to learn the language of the starter, and recognize the development of bacteria as they grow.

Susan describes this mindset as “SR-Being.” “You sort of have to get in this trance of salt-rising bread. I feel I have to get one with the ingredients and the process, and connect with it, and I do better with it somehow,” she says. Jenny adds, “You’re kind of giving it its own rhythm. You’re allowing its rhythm to evolve so you recognize when it’s ready.” (More on that later.)

According to Susan and Jenny, one key way to achieve SR-Being is to try not to stress. This also pertains to worrying about the scary-sounding nature of C. perfringens: Jenny and Susan assure me that not only are the bacteria strains safe when baked (they’re killed off at just below 200° Fahrenheit), bakers have even consumed the starter or raw dough without problems—though for taste alone, it isn’t recommended. “There is not one case of someone getting sick,” Jenny says.

And with that, fellow baker-adventurers, it’s time to make your own delicious loaf of salt-rising bread.

Katheryn Rippetoe Erwin’s Salt Rising Bread

(Adapted from Salt Rising Bread by Susan Brown and Genevieve Bardwell)

Yield: 3 loaves

Ingredients

For the starter:

1 medium potato (Susan’s grandmother specifies Irish potatoes, but any raw potato should work; I used a Russet)

1 tablespoon cornmeal

¼ tablespoon baking soda

¼ tablespoon salt

2 cups boiling water

For the sponge:

2 cups very warm water

½ cup shortening

1 teaspoon salt

4 teaspoons sugar

5 cups flour

For the bread:

6 additional cups flour

Make Your Starter

This is the first and most crucial step of making salt-rising bread; it’s when the cultivation of bacteria occurs, which gives the bread both its flavor and rise. Due to the unpredictability of wild microbes, Susan and Jenny recommend making more than one starter. Sometimes one starter doesn’t work, but another—even right next to it in the same room—does. So it’s good to double your chances.

I chose this recipe for its potato starter, because those tend to be more reliable and are traditional to salt-rising bread. You can also use cornmeal for your starter (see Susan’s recipe on her website), but Susan and Jenny say that tends to be more challenging than the potato version, though the exact reasons why are unknown. A very reliable alternative, which Jenny borrowed from a traditional Greek bread that also uses a C. perfringens starter, uses chickpea flour.

Slice the potato and place it in a jar, then add the rest of the starter ingredients. Make sure it’s a glass jar (plastic tends to result in more failures) or, failing that, a glass bowl. Cover it with a cloth or paper towel to let it breathe (don’t seal with a lid) and let it rise in a warm place until morning. Temperature is key here: If your starter is too cool or warm, C. perfringens spores won’t flourish and grow. A temperature range of 90–110° Fahrenheit (32–43° Celsius) is usually perfect for a salt-rising bread starter. Jenny recommends using a Crock-Pot on the “yogurt” setting (with a few inches of water at the bottom), if available.

If you have a food thermometer to read the temperature (or are just willing to experiment), you could use any warm area around your home: A sunny window, a radiator, and inside or nearby a very low-temperature oven are all good options. According to Susan and Jenny’s research, women traveling with their families across Appalachia often left their own starters to rise in the back of their covered wagons during the heat of the day, so they would be ready to cook on the campfire at night.

While I tried multiple locations, my most reliable experience was leaving my starter on top of my gas stove (all the burners were off) with the oven set to 150° Fahrenheit, which seemed to keep a steady temperature in the jar—though for safety, this might require sticking around the oven. I achieved one successful starter (in a glass bowl covered with a paper towel) by leaving it inside my lidless Crock-Pot on top of a silicone steamer mat with two inches of water at the bottom, too. Anywhere you place it shouldn’t be too hot to the touch.

Watch and Wait (and Smell)

Do not hurry your starter. Pay attention to it. Anywhere from 8 to 16 hours later, a very specific smell with a “cheesy,” “earthy,” or “rotten” quality will emerge. This is exactly what you want. Stronger-smelling starters will often create a tastier bread. “Cheese water!” is what my partner shouted as the smell crept through every room of our New York City apartment for the second day in a row. But to me, the smell is not really quite cheesy at the starter stage; it has its own distinct C. perfringens–imbued smell that some think of as rotten cheese, and which was slightly different from one successful starter of mine to the next. One starter was almost-nutty with a belly-button tinge—I could describe it, politely, as “earthy.”

The starter definitely doesn’t smell good in high doses, and historically this has even caused domestic drama. “That’s part of the lore,” Susan explains. Because of the smell, “husbands are said to have run away and left the house!” But, Jenny adds, “that never kept any of them from eating it.”

One takeaway from my experiments: Starters can surprise you. I thought my first potato starter was a goner. I’m pretty sure I let it go too long, with most of the bacteria dead by morning in my too-hot, radiator-heated apartment. In a last-ditch effort to save it, I opted to turn my oven to 150° Fahrenheit, and kept that jar of starter on top of the warm stove all day, which I hoped would give me a radiating heat of about 110°.

I meanwhile attempted two cornmeal-based starters, one in the same location as the failing potato starter and one in a Crock-Pot. While the cornmeal starters transformed into unusable goo, I found that my original starter had risen to a perfect example of salt-rising goodness, hours longer than the typical timeframe for foam.

Make Your Sponge

Once the mixture has that distinct aroma and has reached a foamy consistency, pour off the liquid and throw away the potatoes. You should see at least 2–4 inches of foam, but not much more, else the bacteria might bloom too quickly and die off in the sponge phase. Once ready, it’s time to pour the water and foam into a bowl to use. Don’t delay this step. You want to use it when it’s at its peak.

Mix the very warm water with the shortening, then add the salt, sugar, and flour. Combine with the starter to make a stiff batter.

Leave the sponge to rise and double in size. This could take up to two hours, but it can happen as quickly as 10 minutes, though that is less common. Once the sponge is ready, it’s time to make the bread. Take care to use the sponge as soon as possible after you see it double in bulk: If you see the sponge start to deflate too much, the bread won’t rise.

Make Your Bread

Work in the flour to make a soft dough and divide in three portions. Let the dough rise in three bowls for 10 minutes. Knead for three minutes, then place it in three greased 8-inch bread pans. Let it rest until the dough reaches the top of the pan. Bake the dough at 450° F (230° C) for 15 minutes, then at 400° F (200° C) for 25 minutes.

While salt-rising bread is not the easiest or foolproof bread to bake, it doesn’t take too long to get the hang of it, as long as you can learn to embrace the chaos of wild bacteria and go with the flow. Even my wonky starter, which had risen twice and had been treated terribly poorly by me, made salt-rising bread at last.

At the end of my project, I’d made two successful starters amid three failures. I’d love to say that I had an exact understanding of my success, but really I think the biggest factor was to let the bacteria do its thing, and check back periodically. It took over a full day to succeed, but the potato starter won out for me in the end, making a dense, fragrant bread that had a nutty, asiago quality that was delicious toasted with butter. In keeping with SRB tradition, the bread was eaten almost as soon as it was baked. I’m already planning to make my next loaf.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

This story originally ran in 2015; it has been updated for 2022.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook