How ‘Used Clothing’ Became ‘Vintage Fashion’

A vintage store on Haight Street in San Francisco. (Photo: ashton/Flickr)

Jeff Gallo, a 51-year-old real estate agent from Brooklyn, was walking through the Staten Island Ferry terminal wearing a vintage trenchcoat, hat, and tie when a group of young police officers started singing the Inspector Gadget theme to him.

It was a slight change from the usual reactions. Sometimes Gallo gets Frank Sinatra songs crooned in his direction. Other times it’s, “What’s with the outfit?” or, “Are you in a movie or something?” It doesn’t faze him, though. Comments from strangers are part of the routine for Gallo, who wears head-to-toe clothing from the 1930s and ’40s on a daily basis.

When someone dresses anachronistically, people usually want to know what statement they’re trying to make. But the meaning of vintage fashion has been changing for the last 50 years—ever since “dressing vintage” became something different than just wearing someone else’s old clothes.

Before the mid-1960s, the idea of wearing an outfit sourced from the wardrobe of a person possibly long dead was unappealing in the extreme. Having endured the rations and restrictions of World War II, Americans had entered an age of gleeful consumerism and were focused on all things shiny and new. Old clothes—referred to as “used,” “worn,” and “secondhand,” were only for those unfortunate souls who couldn’t afford the freshly made stuff.

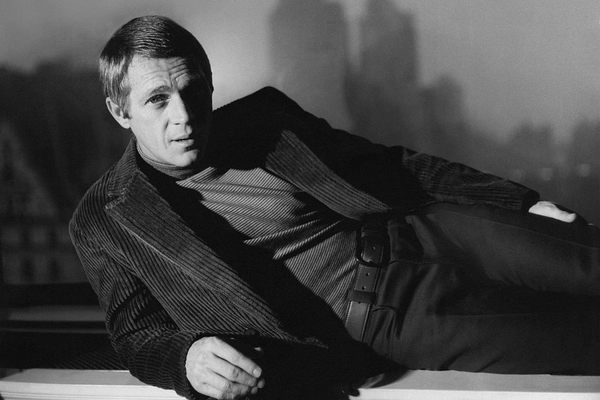

(Photo: Alan Light)

Then came the mods and the hippies, who shook the dust from these cast-off clothes, combined them into novel outfits, and turned the whole thing into “vintage fashion.”

This sartorial revolution began circa 1965, a time when, in the words of a New York Times fashion editorial from 1967, “England’s young began swooping down Portobello Road to buy antique military jackets and delicately handmade Edwardian dresses and, what’s more, wearing them in public.”

The “fancy-dress craze,” as it was dubbed in another 1967 Times article, soon took off Stateside. In New York in 1965, Harriet Love opened Vintage Chic, a boutique that sold what were then known as “antique” garments despite the fact that they were just a few decades old. When she first started selling this clothing, Love later wrote, “you had to be a little weird or theatrical to buy it, let alone wear it on days other than Halloween.”

Meanwhile, in San Francisco, the young hippies of Haight-Ashbury had developed a penchant for the long dresses, lace, and velvet of the Victorian era. By rummaging through closets and thrift stores, they could find flowy, romantic clothing that managed to spurn consumerism, assert individuality, and stand out from the aesthetics of their parents.

As more of these fashion-forward young folk wore secondhand clothing in the later ‘60s and early ‘70s, the prevailing disdain for used clothes began to shift. “Up until a few years ago, wearing some stranger’s old clothes was something only the poorest people did when forced to,” read Cheap Chic, a guide to money-conscious style published in 1975. The book declared that it was “not only sensible but damned exciting to track down beautiful secondhand clothes.”

The New York Times agreed. “Clever women have discovered that antique clothes have a magnificent cut and hand-done details not often found in clothes these days,” the paper opined that same year.

A secondhand clothing store in New Zealand. (Photo: Gwydion M Williams)

In New York, subcultures were coming together at places like the Mudd Club, a TriBeCa nightspot where punk kids crossed paths with rockabilly, reggae, and ska crowds. The music influenced the fashion, which influenced the art, which fed back into the cultural ouroboros, setting off new trends and reintroducing styles from decades past.

One witness to all this was Roddy Caravella, a long-time vintage clothing enthusiast, classic car collector, and teacher of old-school dance styles like lindy-hop, Charleston, and collegiate shag. Lured by rockabilly music, Caravella was hitting up the Mudd Club in the early ’80s, when Madonna, Basquiat, David Byrne, and the Go-Gos were among a crowd that, in Caravella’s words, were “hipsters before hipsters were hipsters.”

To look the rockabilly part, Caravella began by raiding his uncle’s closet. After exhausting that supply, he turned to the downtown thrift stores—Cheap Jack’s; Andy’s Chee-Pees; Starstruck. Such stores, along with army-navy surplus shops, were also on the list of Jeff Gallo, the Brooklyn real estate professional who inspires young policemen to sing Inspector Gadget. In the early ‘80s, Gallo was experimenting with vintage fashion as a proud member of the punk and New Wave movement.

At the time, dressing in vintage styles “was just your way of expressing yourself, by wearing clothes that most people didn’t wear,” he says. This could be a pastiche of eras—Gallo recalls a “really bad ‘40s look” he put together in high school: ’70s trench coat, dodgy fedora, mullet.

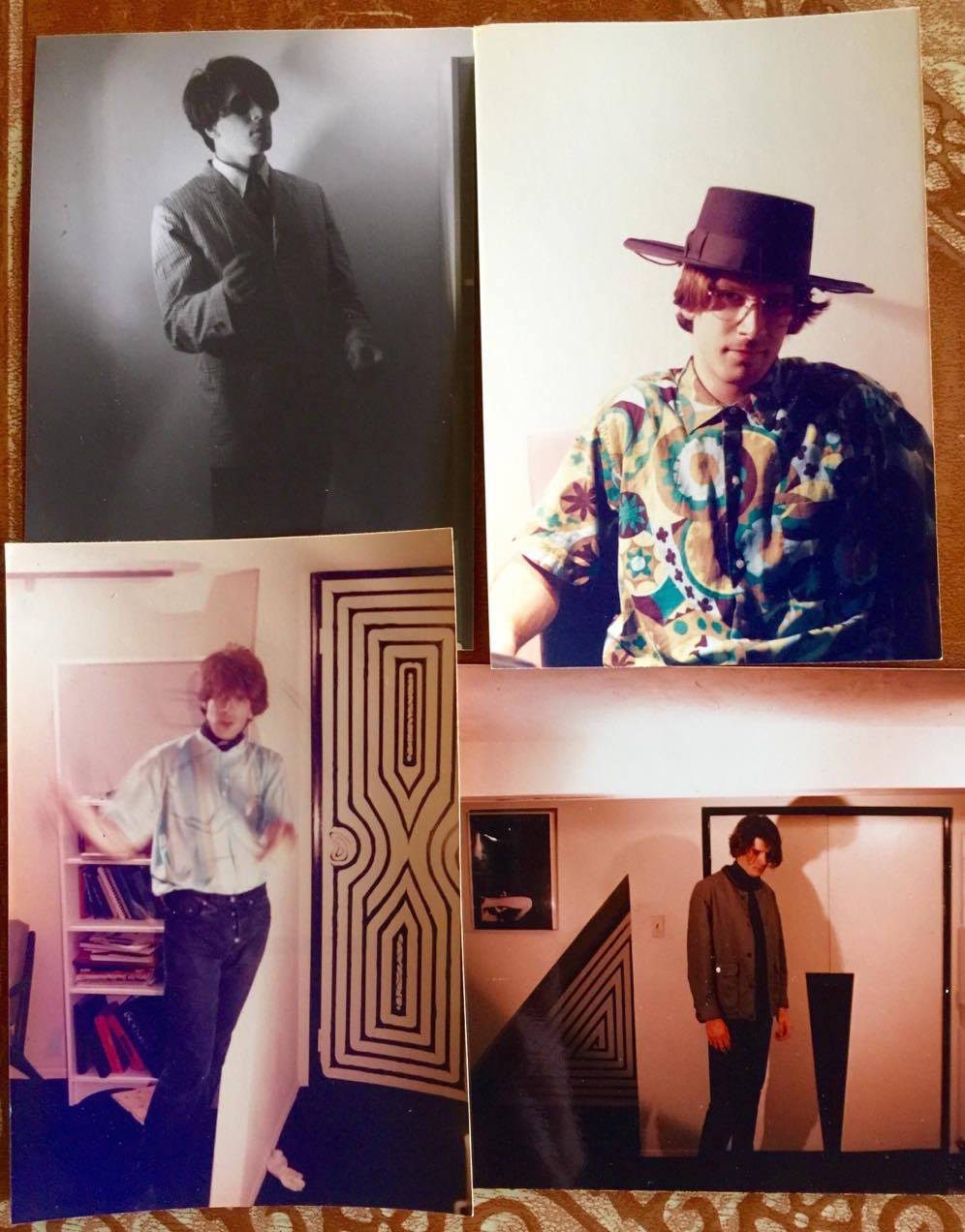

Jeff Gallo “trying way too hard to be cool and mysterious” in vintage clothes, circa 1985. (Photos courtesy of Jeff Gallo)

Though the terms “used,” “secondhand,” and “antique” were still common at this time, the phrase “vintage clothing” had entered the fray in what Retromania author Simon Reynolds calls a “rebranding coup.” Like a fine wine, vintage clothing was coming to be regarded as something of high quality that became even more valuable with age. This perception, and the popularity of vintage clothing in general, resulted in a new problem: scarcity.

”Old clothes with a fashion orientation have become harder to find,” Harriet Love told the New York Times in 1987. Her solution was to add new clothes, made in retro styles, to her Vintage Chic boutique. This vintage-influenced clothing is what’s now known—dismissively, in vintage purist circles—as “repro.”

These days, if you want to wear beautiful clothing from the ’20s, ’30s, or ’40s, you have two options: pricey, often fragile originals, or repro. This state of affairs, along with the ubiquity of information on what styles were worn during each era, has resulted in what Caravella calls the “more vintage than thou” attitude. Whereas in the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s it was perfectly fine to throw together garments from different eras into one pastiche of an outfit, a perfect vintage look now means making sure every component is complementary and period-correct.

Roddy Caravella’s wife, Gretchen Fenston, is a milliner, registrar at Conde Nast, and a fellow vintage style enthusiast. Growing up in San Francisco, home of those pioneering Haight hippies, she says she was nonetheless regarded as “a real freak in college” in her throwback outfits. Fenston and Caravella met through vintage and dance events in New York, and now live in a Brooklyn home filled with Art Deco decor. Three vintage cars—two from the ‘20s, one from the ‘30s—sit in garages out back.

Gretchen Fenston and Roddy Caravella. (Photo: Voon Chew)

Like Caravella, Fenston has little tolerance for vintage snobbery. When it comes to high-quality, pre-1950s clothes, there is “a finite amount of stuff, so people start to get prickly about it,” she says. “It’s like, ‘You’re not as good as us because your underwear isn’t correct.’” Competition for the best clothing is fierce, and purists, says Caravella, “don’t want you to have it if you’re not wearing it 100 percent right.”

Getting an entire vintage outfit exactly authentic is a very difficult task—both in terms of the money required and the time it takes to track everything down. And for most people, precise accuracy isn’t the goal—nor is it in the spirit of the improvisational, pastiche-style origins of vintage fashion. “I think you have to let people enjoy vintage to whatever degree they like to enjoy it,” says Caravella. That could mean wearing a mix of vintage and repro, wearing an outfit sourced entirely from 1936, or just throwing on a ’60s-style dress every now and then.

A big shift in vintage fashion over the last few decades has been the rise of online retailers and auction sites. In the ‘80s, says Caravella, you had to keep your ear to the ground to find the good stuff. A friend would call him up and say “Joe at Starstruck on Bleecker Street just got a shipment in of new-old stock shoes … Get over there quick!” Now it’s all about using the right search terms on eBay and Etsy, where with a few clicks you can buy vintage items from all over the world.

“Everyone’s on eBay, everyone’s sniping,” says Caravella. “And I’m as guilty as the next guy. I’ve been buying stuff from this guy in Montana.”

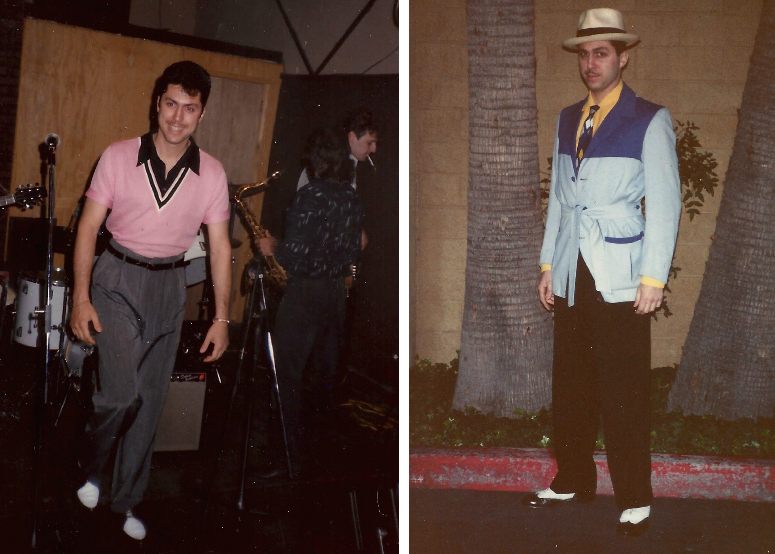

Roddy Caravella rocking vintage looks in 1980 (left) and 1990. (Photos courtesy of Roddy Caravella)

Online stores, says Fenston, have “changed the way we buy and sell, because when you buy something online you can’t try it on.” When people take the items that don’t fit and sell them to other vintage enthusiasts online, they contribute to “this open pool of buying and selling rather than a whole bunch of people going into one place to buy.”

The internet has also made it far easier to pore over vintage looks, learn how to style hair and apply era-specific makeup. Reference images and video tutorials are but a Google search away.“Years ago you had to buy books or a certain movie to be able to see it again,” says Gallo. Now, “people have such a hyper awareness of what the true look was, because they can research it.”

As for what eras of clothing and style tend to appeal most, trends in pop culture influence the popularity of certain decades. In the 1990s, swing dancing and ska revivals brought ‘40s suits and circle skirts back into the spotlight, while the ad agency drama Mad Men, set in the ’60s and ’70s, upped the demand for skinny ties and wiggle dresses. Popular online stores like ModCloth and Unique Vintage offer brand-new versions of retro styles, allowing those who dig the aesthetic to look vintage without having to hunt for old clothes.

Ironically, the inexpensive, improvised, anti-consumerist vintage fashion that the mods and hippies invented has given way to a form of vintage fashion that is consumerist, often expensive, and more restrictive in terms of what the “correct” way to wear it might be. But for those with a genuine love for the workmanship and details of old clothing, wearing vintage is still a joy. The hunt for the perfect piece on eBay is still thrilling. And the self-proclaimed “oddballs” and “freaks” like Caravella, Fenston, and Gallo, who have been dressing this way for decades, get their photos snapped at events, and regularly end up in the Style section of the New York Times.

Day-to-day however, people still stare and ask questions. In the decades since his youthful, punk-influenced dalliances with vintage, Gallo’s style has settled into a more refined ‘30s and ‘40s look—a style that also characterizes the decor of the home he shares with his wife, fellow style maven Martha Gallo, and their two children. When he walks out the door and heads to his work as a real estate agent, “people just don’t know what to make of me sometimes,” says Gallo. “One woman said to me, ‘Boy, when I first saw you I thought you must be a real jerk. You know, [because of] your whole ‘look.’”

Jeff and Martha Gallo in 2013. (Photo courtesy of Jeff Gallo)

Gallo is not, by any means, a jerk, but he does use clothing as a kind of buffer against the world. “I never felt comfortable in my own skin,” he says. For him, vintage clothing feels right—“almost like a comfortable blanket,” a way of “keeping the 21st century at bay.”

The retreat into styles of yore is a centuries-old phenomenon—Fenston points out that in the middle of the 19th century “people were afraid of the industrial revolution, so people went back to a lot of crafting and wearing things that looked like they were from an earlier period.” Clothing can provide comfort in more ways than one.

Fenston herself has one word that sums up why she wears vintage daily: “confidence.” Likewise, Caravella dresses to suit himself. “It’s for me. This is who I am,” he says. “This is what makes me happy.”

This story appeared as part of Atlas Obscura’s Time Week, a week devoted to the perplexing particulars of keeping time throughout history. See more Time Week stories here.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook