The Effort to Bring Sail Freight Back to New York’s Hudson River

What’s old is new again.

At any given moment, more than 20 million shipping containers full of raw materials and finished products and everything in between are crisscrossing the ocean, neatly stacked on ships. Other goods travel by rail or plane. Even the hyperlocal produce at your nearest farmers’ market was packed into a truck and driven there. The shipping industry makes our modern global economy tick. But before engines powered trains and trucks and ships, moving goods any considerable distance relied on wind and water. A new project on New York’s Hudson River is looking to bring that spirit back—with carbon-neutral local sail freight.

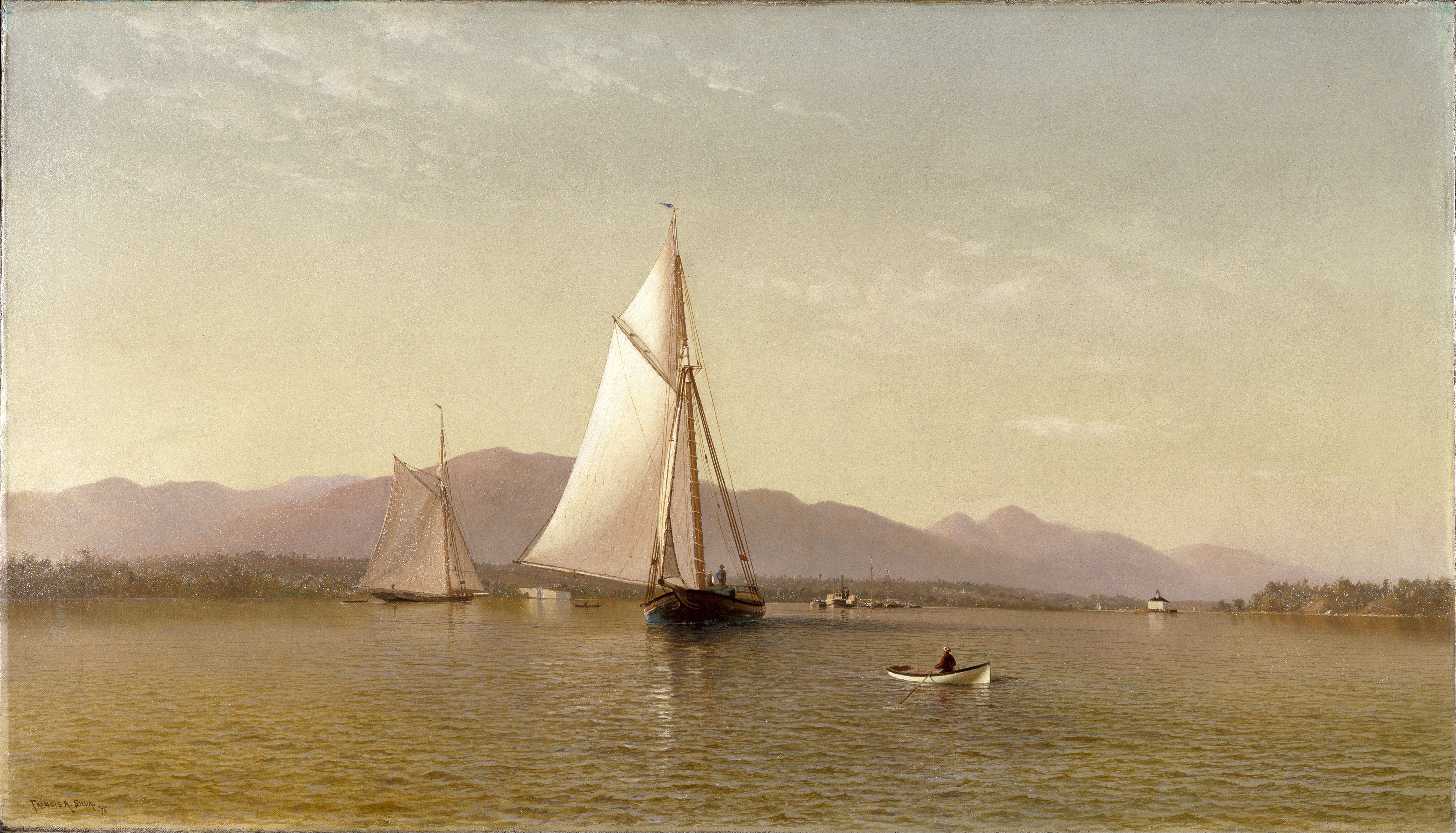

The Hudson River starts up in New York’s Adirondack Mountains, runs through Albany, down between Manhattan and New Jersey, and ends at New York Harbor. South of Troy, it’s considered a tidal estuary, with brackish water rising and falling by as much as six feet every day. The waterway has always been an important route for moving people and things, first by canoe, and then later by sloop. Sloops, single-mast sailboats, were a common Dutch style that first plied the river in the 17th century. A trip from New York City to Albany by sloop took roughly a week, depending on winds and tides, and could only be made in warmer months when the waterway wasn’t iced over. It was all much too slow for moving perishable goods.

Things sped up a bit in 1807, when the first steamer ship made the trip, in about a day. Fruit, milk, and impatient passengers could be moved upriver with relative speed. Later steamers were faster, and dedicated passenger steamers added comfort to the trip, a popular leisure option through the 1920s. The construction of a railroad line in the middle of the 19th century, however, changed the local shipping industry. Perishable goods were sent by rail, while heavier bulk goods, such as construction materials, coal, large blocks of ice, and grain, were still loaded onto steamers.

By the mid-20th century, industrial river traffic consisted mostly of barges, and communities turned away from the water. Hudson, for example, “was built as a city that was interacting with the river, but then there certainly was a period of time when that was forgotten,” says Sam Merrett. Merrett is captain of the schooner Apollonia, the new sail freight project. “There used to be a bay south of town where all the big sailboats would dock, and that bay literally got cut off when they put in the train track. It’s now completely sedimented and silted in. You wouldn’t even recognize it as part of the river, it just looks like a kind of wetland-y marsh zone.”

Many Hudson River towns still have some waterfront infrastructure, historically used for loading and unloading cargo, but dockage is now a major challenge for a ship like Apollonia. Jason Marlow, a sailor on the schooner, points to towns such as Cold Springs and Peekskill as places where residents are enthusiastic about developing riverfront access. Towns on the western side of the river, such as Athens, New York, are also ideal, as they don’t have a railroad blocking their river access.

The boat that Merrett and his crew have enlisted is a 64-foot-long, 15-foot-wide, steel-hulled schooner that was built in Baltimore in 1946. In addition to sails, the ship has a diesel engine—readied to run on used vegetable oil—to help it maneuver 20,000 pounds of cargo. The crew is partnering with local businesses along the river to offer an alternative to moving products by truck. The Apollonia is almost ready to carry freight on the Hudson next spring. The team is working on funding their final step—a mast and rigging for the ship’s salvaged-material sails.

Just like sail freight in the 18th and 19th centuries, the Apollonia won’t be speedy enough for perishable goods. But the steel schooner is perfect for carrying heavy, shelf-stable products—think beer, wine, or cider. And the route should run both ways. A sea salt producer in Germantown, New York, needs saltwater to freeze and evaporate, so Apollonia will have a bladder, “like a Camelbak,” says Merrett. “If we’re ever down in New York [City] and don’t have a load to bring back up, we can just go off shore a little bit, pump some clean salt water in, and that can be our load coming north.”

“A regional, local focus is an important thing, including how we get things to and from a place,” says Marlow. “You can get anything from anywhere, [so] why would you want it from here? Because it’s special, this is where we live.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook