Impaled Horse Heads Are Appearing More and More Around Iceland

The rise of paganism in the country is reigniting a macabre ritual from the Viking Age.

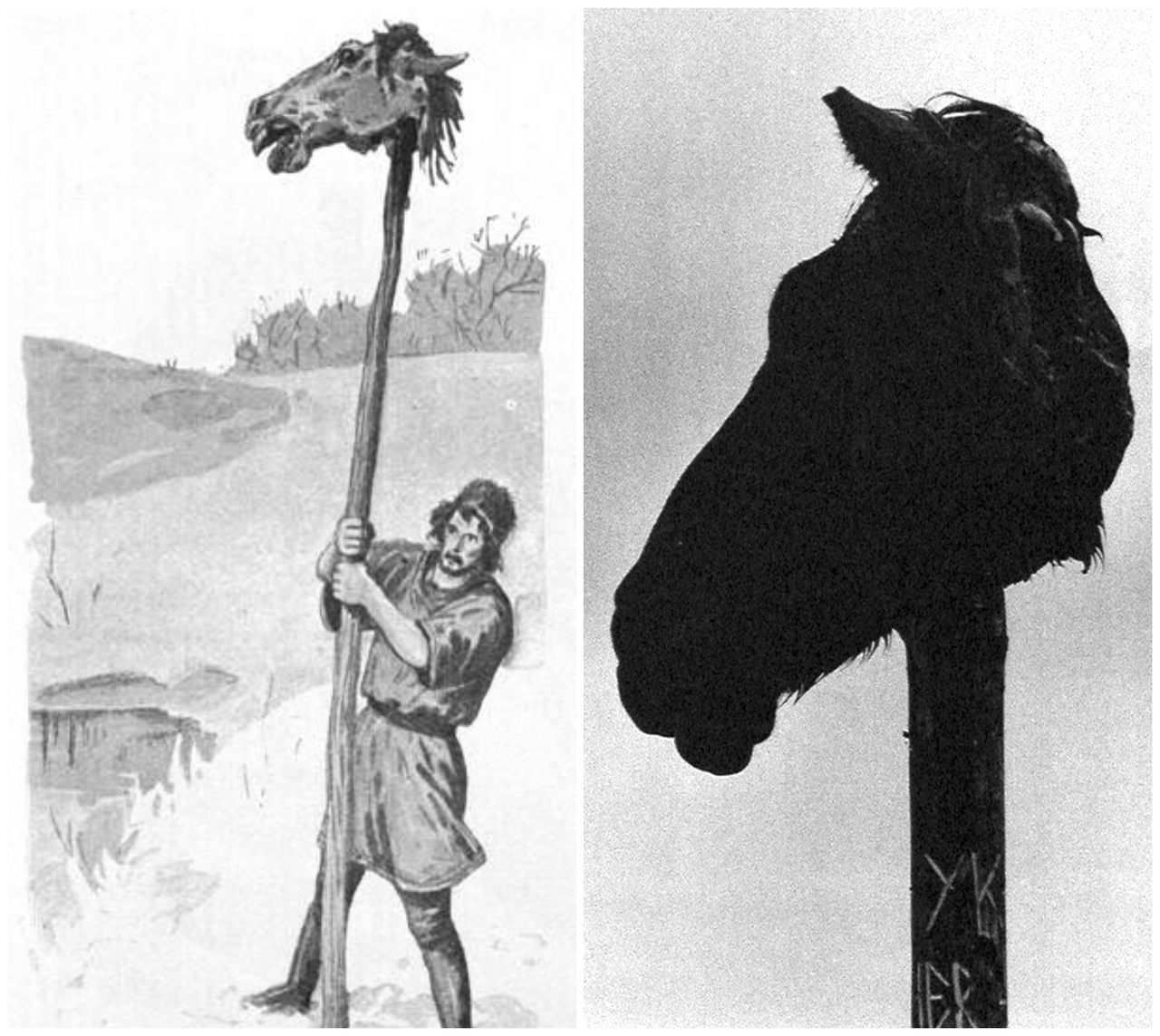

On the morning of April 29, 2022, members of a new-age commune outside of Reykjavik woke to a freshly severed horse head on a wooden pole pointed at their property. Any local who saw the grisly scene, blood-caked and mouth agape, would have immediately known what it meant.

The Icelandic níðstöng (“nithing pole” or sometimes called a scorn pole) is a curse dating back to the Viking Age. It is believed to have been used as early as the 10th century to hex unwanted guests, and the self-described spiritual community of Sólsetrið was quite unwelcome in rural Kjalarnes. Their bohemian congregations, plus the drumming ceremonies and group mushroom trips, just weren’t sitting well with the neighbors. It was actually Guðni Halldórsson, the avid equestrian living next door, who discovered the nithing pole that morning. He initially believed it was directed at him, due to ongoing disputes with Sólsetrið.

A day later, Halldórsson cleared it up on Facebook: “We in Skrauthólar have received an anonymous tip that [the nithing pole] erected in front of our house yesterday was not directed at us,” they wrote in Icelandic. “The action is against the activities of [Sólsetrið] and the alleged violence (mental and sexual) that the person in question claims to take place there.” Those claims have not been proven, but Halldórsson goes on to say, “We who live in Skrauthólar and are part of a civilized society are victims in this case and end up there in the firing line.”

Nithing poles such as this have been popping up in Iceland more and more over the last few decades. Anna Björg, CEO of the Museum of Icelandic Sorcery and Witchcraft in Hólmavik, says nithing poles are “pointed against someone you want revenge on” and considered deeply personal. She explains that it’s more serious when directed at an individual as opposed to a larger entity, such as an industry or the government. Björg says, “People take it like a death threat.”

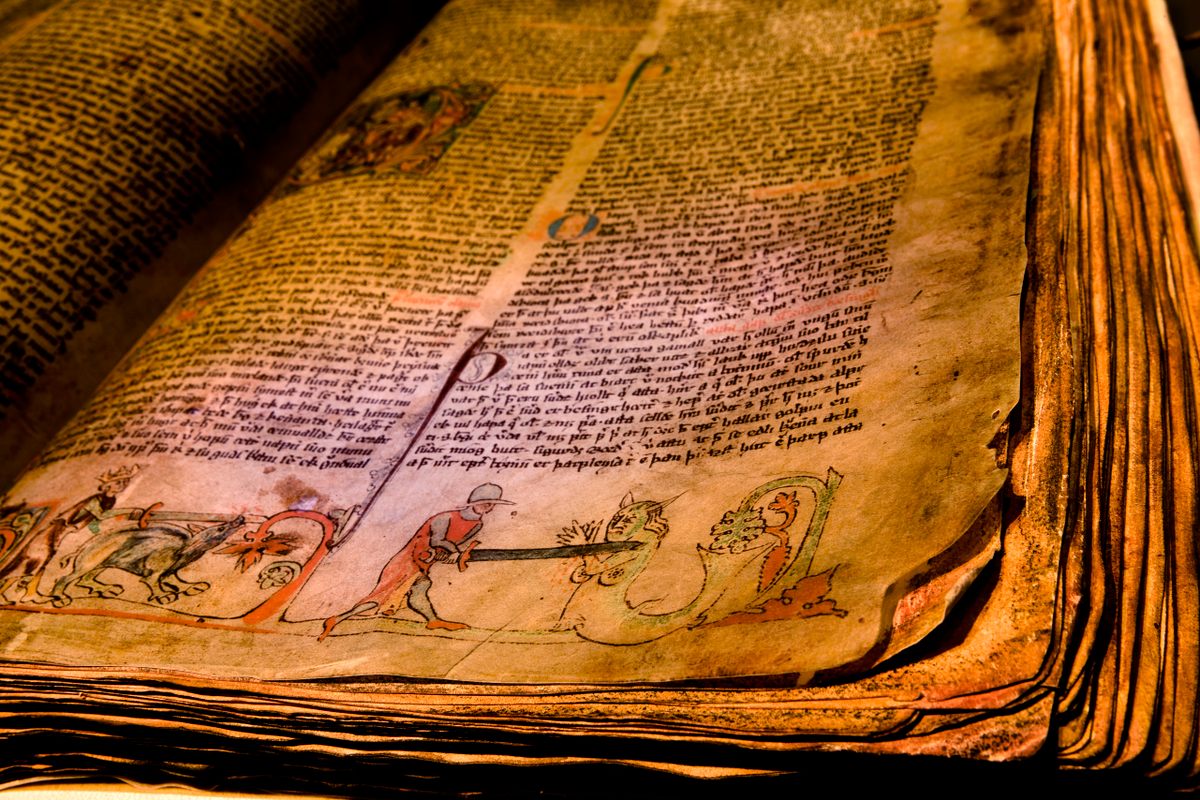

The curse of the nithing pole was born in the sagas, a series of texts narrating Iceland’s history through legends of trolls, elves, and giants. Its earliest known mention is described in Egil’s saga, written during the 13th century about the family of Egil Skallagrímsson, who lived between 850 and 1000. “Egil went up into the island. He took in his hand a hazel-pole, and went to a rocky eminence that looked inward to the mainland,” the text reads. “Then he took a horse’s head and fixed it on the pole.”

Egil says in his namesake saga: “Here set I up a curse-pole, and this curse I turn on king Eric and queen Gunnhilda.” He then calls upon the landwætta (land-spirits), saying, “This curse I turn also on the guardian-spirits who dwell in this land, that they may all wander astray, nor reach or find their home till they have driven out of the land king Eric and Gunnhilda.” Egil proceeds to plant the nithing pole, horse’s head turned towards the cursed, and cut a poem on the pole in runes, thus “expressing the whole form of curse.”

These stories still reverberate from the bustling capital to the sleepiest fjords, although most Icelanders don’t take the folktales about their island’s earliest settlers literally. Though the sagas are generally accepted as fiction, they are supposedly rooted in true stories.

Tómas Albertsson of Eyrarbakki is a researcher of galdur (Icelandic for “magic”) who collects books on sorcery, old manuscripts, and “magic things” in general, including various scorn pole memorabilia. Albertsson explains that the níðstöng is “related to tréníð, called poem-pole, and again to marar-póll (nightmare-pole), which is from Sweden. So it has base in the oldest law books.” Of the references to the nithing pole in Egil’s saga, specifically, Björg also confirms: “I think we can say that they were true.”

Certainly one group in Iceland believes them to be true. A modern form of paganism called Ásatrúarfélagið, or “Ásatrú” for short, is more serious about Icelandic mythology. The sagas, in some ways, serve as their scripture.

Translated from the organization’s website, Ásatrú aims “to promote and respect ancient customs and ancient cultural values” and “to increase understanding and interest in folklore and old traditions.” The fellowship was founded in 1972 and officially registered as a religion a year later. In 2017, just 45 years after it was established, the National Bureau of Statistics declared Ásatrú as Iceland’s fastest-growing religion. It currently claims 5,000 followers, which is 1% of the population. After Christianity, Ásatrú is the most-followed religious organization in Iceland.

The country’s first pagan temple in 1,000 years is now under construction and nearing completion in Reykjavík. Today, the followers (who call themselves Heathens) continue to reignite the Viking spirit, once again donning their traditional tunics and tipping their drinking horns to Norse gods and goddesses.

Ásatrú members certainly believe in the curse of the nithing poles, though it’s not the easiest ritual to pull off in this day and age, according to Hilmar Örn Hilmarsson, Allsherjargoði (chief official) of the Ásatrú fellowship. And that difficulty is not just because the cursemaker requires access to a freshly severed head. “Nobody has agreed upon how you do it, except that you have to have a poem, and you have to carve the poem with the runes into the pole carrying the horse head,” Hilmarsson says. “That’s what we’re told in the Icelandic saga.”

Since Ásatrú was founded, the níðstöng ritual has been attempted a few times against the Icelandic government. In the ‘70s, one was erected to oppose Union Carbide’s plans to build a ferroalloy plant on the west coast. Then in 1979 and 1985, more went up, both against the country’s NATO membership.

In 2006, when a Westfjordian man planted one against his neighbor, he was consequently charged with threatening the neighbor’s life. Then, a year later, the grassroots lobbying organization called Saving Iceland planted a pole in the hand of a prominent statue outside the parliament building. Overlooking Austurvöllur square, the bronze depiction of Iceland’s “independence hero” Jón Sigurðsson appeared to hold the stick, topped with a horse’s skull painted with runic symbols. The pole, aimed at parliament, targeted politicians who voted in favor of a hydropower project that Saving Iceland deemed “environmentally destructive.”

The act was replicated in 2020, when a pole with “burning heads” and a sign stating that parliament “oppressed women and those less fortunate” was erected at the same statue, according to a local daily newspaper.

But these instances don’t all successfully work the dark magic they were intended for, according to Hilmarsson and Albertsson. They both agree that the nithing poles of late, including the most recent one targeting Sólsetrið, don’t include the detail needed to officially qualify as nithing poles.

“The poet/cursemaker has to write the poem on the stick (pole) upside down by its own end (making eight lines),” Albertsson says. “Blood is not meant to run down the letters.” One problem, according to Hilmarsson, is that not many people know how to write in runes. Another is that the head on the pole must belong to a horse, not any other animal.

The nithing pole erected in 2006 in the Westfjords was crowned with a calf’s head, the one outside parliament in 2020 with heads of sheep. It’s unclear whether either pole used was etched in runes.

Another form of scorn pole that still periodically rears its head around Iceland is the vindgapi, which is topped with a severed fish head. Traditionally, the fish is a ling, looking especially sinister with its sharp teeth and large, bulging eyes. This symbol is often called a nithing pole, but its purpose is not to curse an individual. It’s a “weather curse,” Hilmarsson says, meant to conjure storms. A replication of the vindgapi is on display at the Westfjords’ Museum of Icelandic Sorcery and Witchcraft, which describes the curse as follows:

“Take the head of a ling and carve the stave vindgapi on it and with a raven’s feather apply blood from the right foot into the stave. Put the head on a pole and raise it where land meets sea, point the mouth in the direction you want the wind to blow from and the higher the mouth is pointing the more forceful the wind you call will be.”

The museum references a story from the 1800s of a man who was exiled for planting a vindgapi and purportedly causing a heavy storm in which two fishing boats were lost off the coast of the remote Strandir region, where the museum is. The ritual dates back to at least 1698, Albertsson says. Like the nithing pole, it is still used today—if not as a real curse, then as a threat or at least a theatrical means of protest. A vindgapi topped with a cod’s head was discovered in the Westfjords in 2018, supposedly planted in opposition to salmon farming in the region.

Although Albertsson says some Icelanders do still believe in the curse of scorn poles, Hilmarsson calls acts such as these “publicity stunts” and says they’re mostly used to “send out a message to people who either practice some sort of magic or believe in magic in a way that makes sense.” Speaking on behalf of Ásatrú, he called the modern use of nithing poles “futile” and says the organization has distanced itself from rituals of animal sacrifice such as these.

Björg says she sees the ritual as a last resort. “You feel powerless but want to fight, so even if there is no special ceremony or runes, I think just the intention has power.” It’s now been more than a year since a bloody horse head appeared near the Sólsetrið commune, and authorities still haven’t identified the culprit. The community continues to practice an alternative lifestyle at the dead end of a farm road in Kjalarnes, even inviting tourists to stay at their encampment and dance around the fire on the slopes of Mount Esjan where they live.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook