How FDR Used Famous Immigrants to Extoll America’s Greatness

“I’m an American” was the U.S. government’s attempt to promote tolerance in the run-up to World War II.

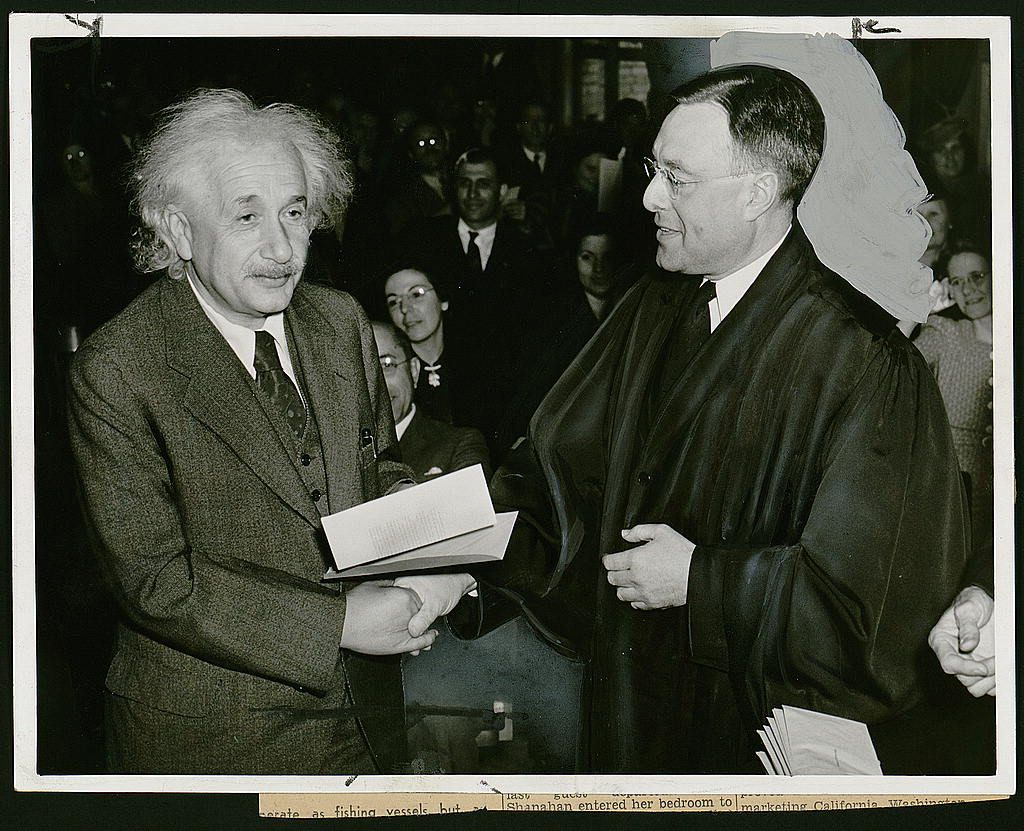

On May 4, 1940, the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) launched a radio show called I’m an American. On each episode of this short-lived and long-forgotten program, an INS employee interviewed a “distinguished naturalized citizen”—among the famous actors, scholars, musicians, artists, and politicians who appeared on the show are Thomas Mann, Frank Capra, and Albert Einstein. These luminaries were paraded out to extoll the joys of American citizenship—“a possession which we ourselves take for granted, but which is still new and thrilling to them,” as the show’s announcer put it—and to promote the United States as a beacon of tolerance and democracy. (Listen to full-length episodes of the show below.)

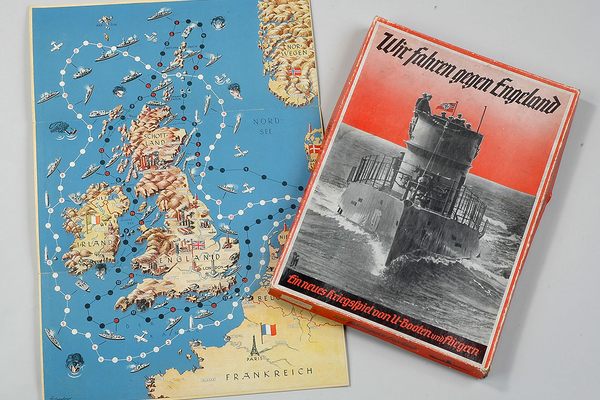

The America portrayed in the show is one of the more inspirational takes on the country: the melting pot, the nation that mobilized to defeat the Nazis and brought freedom to Europe. But even though the government was trying to convince the American public about the advantages of immigration, there were limits to this embrace. The government was only ready to accept some immigrants as loyal Americans.

As a collection, the interviews can be both charming and awkward. They are weighed down, at times, by the expected tedium of any government document, and are shadowed by the power the government held over immigrants—not all of whom were as welcome as the show made it seem. The dialogues on the show were carefully crafted by government officials: They began with written answers submitted by the interview subjects, but every line was approved, and sometimes scripted, by an INS employee. While the official interviewers are often stiff and halting in their delivery, one sign of the guests’ brilliance is how well they pull off their parts, despite some thick accents. Listen, for instance, to Attilio Piccirilli, the Italian-born, Bronx-based sculptor perhaps best known for his work on the U.S.S. Maine National Monument in New York’s Columbus Circle:

The interviewees told personal stories of their journeys to America or discussed the ideals of America and the country’s role in the world. Part of the show’s purpose was to portray America as the land for “lovers of freedom, the refugees of intolerance, the fighters for liberty of man,” as the introduction to a published collection of the interviews puts it. European immigrants who fled rising fascism had a personal stake in American democracy and understood what was at risk across the Atlantic. The author Thomas Mann, who had been a vocal opponent of the Nazi Party in his native Germany, spoke powerfully about the need for democracy to triumph over totalitarianism:

In 1940, when NBC began to broadcast the show on Sunday afternoons, the United States had not yet entered World War II, but President Roosevelt believed it would happen. However, this sentiment was not broadly shared by the American people. As government propaganda, the show had a clear goal to promote a spirit of internationalism, head off the anti-immigrant sentiment that hampered America’s efforts in World War I, and gin up support for American intervention in Europe.

“It’s a great example of the ongoing tension between the Roosevelt administration and the isolationist flavor of the country at the time,” says Gerd Horton, a history professor at Concordia University and author of Radio Goes to War, which examines the role of American radio in World War II. “This was a time when Americans were not very eager to take in immigrants, including Jewish immigrants. In a way, President Roosevelt was treading on thin ice a little bit, and the Republicans went after him wherever they could, trying to curtail the New Deal programs and this socialist nonsense. I’m sure they were not happy to hear this program to go on the air.”

While plenty of the guests on I’m an American spoke with unalloyed patriotism and enthusiasm, not every interviewee was at ease with the administration’s propaganda project. One early guest, the historian Hendrik Willem Van Loon went off-script and tried to call attention to the show’s charade of informality. Listeners, he said, were smart enough to know the whole script had been approved ahead of time. Ludwig Bemelmans, the children’s book writer and illustrator who created the Madeline series, insisted, “You see I am not the person to go for a message or to advise naturalized citizens how to be good Americans.”

When movie director Frank Capra was asked to appear on the show, he felt pressure to prove his loyalty to the government, his biographers write. As an Italian-American and a member of the Hollywood community, which had long been held in suspicion for left-leaning tendencies, even the director of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington was vulnerable to accusations of un-Americanism. Capra was no longer so keen on creating “message films” such as Mr. Smith, but he went along with the government script that had him praise his own film:

Well, I think that picture, well, it was American in spirit. The hero was a young legislator, green about politics but with a good sound American character, and he wasn’t afraid to criticize what he saw that was wrong. It think Americans liked it because he was the underdog and he would speak right out.

Capra was also asked, in preparation for the show, to “give a defense of Hollywood and its people, showing their strong sense of Americanism and loyalty to democratic ideals.” On the show, he said, “Hollywood is no more an offender on this score than any other community. Naturally we have left and rights and middles and ups and downs—mostly ups and downs—but not more than any other place.” But according to Joseph McBride, author of Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success, the director’s original response was to attack the Hollywood left and the community’s immigrants from central Europe so sharply that the INS decided to soften the language.

Capra wasn’t wrong to worry. During World War I, nativism had swept through America, and immigrants faced discrimination so acute it hampered the war effort. The sentiment was again rising in the 1940s, and the federal government was keeping a close eye on its immigrant population. Not longer after I’m an American started airing, Congress passed the Alien Registration Act, which gave the government increased leeway to deport immigrants for their political views and required noncitizens to register with the government. According to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, one of the successor agencies to the INS, at one point the I’m an American broadcasts included reminders for noncitizens to register their locations by the December 1940 deadline. These same registration lists were used later to locate Japanese-Americans and imprison them in internment camps.

If I’m an American was an effort to argue for the mutual benefits of immigration to America, its vision of a diverse country was limited. The government was pushing for acceptance of eastern and southern Europeans—Jews, Italians, Greeks, Poles—as good Americans, but not African Americans, Japanese Americans, and others. “There’s no question that Asian Americans and Latino Americans are outside of this,” says Robert L. Fleegler, a historian at University of Mississippi and author of Ellis Island Nation. It wasn’t even legal for Filipino and Indian immigrants to become naturalized citizens until 1946.

Laws such as the Alien Registration Act reveal what Nancy Morawetz, a clinical law professor at New York University who specializes in immigration rights, calls “an internal battle for the soul” of the INS. The agency was responsible for the dueling missions of immigration enforcement and promoting naturalization. When enforcing the Alien Registration Act, for instance, the INS found room to forgive people who didn’t have the right papers, or who might otherwise qualify for deportation. “It’s not as though these were benign laws,” says Morawetz. “It was the first step toward internment. But it was not thought of as being universally inconsistent with an embracing of immigrants.”

Within limits, the Roosevelt administration was dedicated to promoting tolerance—for European immigrants, at least. Perhaps the clearest expression of this spirit is the campy program the INS created for the first “I’m an American Day,” celebrated on May 18, 1941. In a triumphal moment, the announcer lists the many places that immigrants had come from and what they had contributed to the country:

Ultimately, for the groups embraced by the administration, the propaganda worked. In the story that’s now usually told about American history, these select groups of people are a core part—if clearly not all—of what defines Americanness.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook