When Indian Hosts Opened Their Homes to Pakistani Cricket Fans

India and Pakistan’s volatile relationship keeps their citizens apart. Cricket brings them together.

“You haven’t been born until you’ve seen Lahore,” says Kanwaljeet Singh. A resident of the city of Mohali in Punjab, India, Singh is quoting a regional saying. Yet Singh has never seen Lahore. While he’s lived all his life less than 150 miles from the Punjabi cultural and literary center, he’s never been able to cross the India-Pakistan border to go there.

He’s far from the only one. Since the 1947 Partition of British India into India and Pakistan, Punjab has been bifurcated by a heavily militarized national border—and a daunting visa application. With relations between the two countries in constant turbulence, getting a visa to visit either side “is really damn difficult,” says Kausik Bandyopadhyay, Associate Professor of History at West Bengal State University. There are few exceptions, mainly for religious pilgrims, students, and artists. Even these visas are often limited to a handful of cities, and visitors are required to register with police. There’s another route, though, through which Indian and Pakistani citizens can visit each other’s countries: for a cricket match.

It’s hard to overstate the sport’s influence. The British brought the ball game to the region, but Indians in the 19th century embraced it. Post-independence, South Asian countries used the sport to assert national pride. The Indian Premier League is currently valued at over $6.3 billion, and over a billion people tuned into the India-Pakistan match during the 2015 ICC Cricket World Cup. But cricket is more than a sport: it’s a geopolitical force. The term “cricket diplomacy” as a tool of statecraft originated with Pakistani president Zia ul-Haq’s 1987 visit to Delhi, according to Bandyopadhyay. Ostensibly there to see a test match between India and Pakistan, ul-Haq used the event to negotiate with Indian officials in an increasingly hostile diplomatic climate.

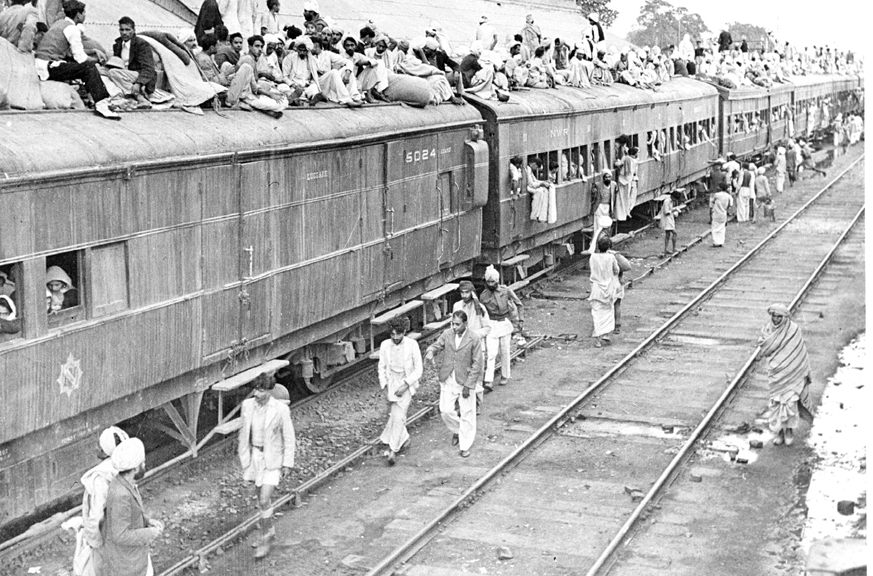

This hostility has its roots in the brutal 1947 Partition of British India. Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the first Pakistani head of state, and his Muslim League had promoted the creation of a separate country to give the subcontinent’s minority Muslim population their own homeland. With the British in favor of the Partition, millions of Indian Muslims travelled to the newly created country of Pakistan, and millions of Hindus and Sikhs headed to India.

But when the migrations began, religiously charged rhetoric exploded into unthinkable violence. In the ensuing riots, countless women were raped, and up to two million people were killed. It also was the single largest mass migration in human history, with an estimated 16.7 million people displaced. This traumatic legacy has contributed to an uneasy rivalry between the two countries ever since.

Yet in April of 1999, it was cricket that brought a piece of Lahore to Kanwaljeet Singh. With India and Pakistan slated to play each other on Indian soil for the first time since 1987, the excitement in Chandigarh’s well-manicured streets was palpable. Fans from India and Pakistan came to watch the game: so many, that local hotels ran out of rooms. The city administration printed an appeal in the local newspaper, asking residents to host Pakistani guests in their homes.

Singh, a high school student at the time, had grown up listening to his grandmother reminisce about her childhood on the Pakistani side of the border. Fascinated by these stories, and by the literary legacy of Lahore, Singh was curious about his neighbors to the west. When he and his classmates heard that the Pakistani fans had arrived, they dashed to greet the crowds at a nearby plaza. He remembers asking: “Are you from Lahore? Are you from Lahore?” His family volunteered to host two families from Pakistani Punjab. “There was an air of excitement and curiosity,” Singh says. “It was like a festival.” Singh remembers an entire village near his home turning out to welcome his family’s Pakistani guests with flowers. One restaurant was so crowded with Chandigarh residents and their Pakistani guests that diners spilled out onto the surrounding plaza. The restaurant owner called for a dhol, a drum common to both sides of the border, and the crowd danced in the hot April air.

1999 wasn’t the only year Chandigarh residents hosted Pakistani cricket fans. It also happened in 2011, when fervor over the India-Pakistan World Cup semi-final in Mohali led to such severe overcrowding that the city government called for everyday residents to turn their homes into hotels.

Before that match, Pramod Sharma and Diep Saeeda joined the frantic queue outside Mohali Cricket Association Stadium to greet Pakistani fans. Sharma is president of Yuvsatta, “Youth for Peace,” and Saeeda is a Pakistani peace activist and the founder of the Institute for Peace and Secular Studies, a Lahore-based grassroots organization that has led an ongoing campaign to decrease visa barriers between Indians and Pakistanis. Saeeda and Yuvsatta members handed out 10,000 Indian and Pakistani flags, each pair tied together with string. “Some threw the Pakistani flag away and took just the Indian flag,” says Saeeda. “But most people were friendly.”

Besides regularly traveling to India, Saeeda frequently hosts Indian guests. When she visits India, says Saeeda, some Indians are shocked that she is Pakistani, believing that Pakistani people must look or behave differently than themselves. This kind of belief is at the heart of the two countries’ enmity, says Aaliyah Tayyebi, senior project manager of the Oral History Project at the Citizens Archive of Pakistan, so face-to-face encounters can be transformative.

For the relatively few Pakistani and Indian people who have been granted visas to cross the border, the experience can feel like a family reunion. According to Sharma, one Pakistani family that stayed in Chandigarh during the 2011 match delayed their daughter’s wedding for a year so their Indian hosts could obtain a visa to attend it. When Singh’s family and their guests discovered the same surname in their family tree, Singh began calling his Pakistani elders maama, or maternal uncle. “They weren’t really our relatives,” says Singh. “But they became family.”

This aura of hospitality has had an enduring effect on the way Singh views his country’s neighbors. Since the 1999 match, says Singh, when he hears someone characterizing Pakistanis and Indians as natural enemies, he recalls his family’s guests and rejects the jingoism. For Bandyopadhyay, this is a testament to sports’ role in person-to-person diplomacy. “Cricket has the power to humanize the relations that had been dehumanized over the years due to the scars of Partition,” he says.

Still, Bandyopadhyay fears that without a political solution to the tensions between the two countries, cricket diplomacy can only go so far. Hopes were high that the 1999 India-Pakistan match, the first on Indian soil in almost a decade, would result in some reconciliation. But the bonhomie was cut short by the breakout of the Kargil War. In 2011, Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari even attended the World Cup semi-final together in the Mohali cricket stadium. Yet the goodwill didn’t last long. In 2013, the countries faced off over the disputed area of Kashmir once more. Not even cricket can entirely escape the enmity: Indian officials once leveled sedition charges against citizens who supported the Pakistani team. “Whenever cricket was thought to be an instrument of peace, something untoward happened,” says Bandyopadhyay.

For Singh, however, cricket isn’t the point. He vividly recalls the friendships he formed during the 1999 match, and doesn’t even remember who won. “Nobody went to see the match,” Singh laughs. “Nobody was interested in cricket at all.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook