Cook Your Way Through Regional Indian Recipes With This Online Archive

A student project is digitizing the subcontinent’s community cookbooks.

Zahra Azad’s recipe for gulgulay contains precise instructions for cooking, but also for serving the sweet. Made by frying balls of sweetened flour in oil, it is “Perfect for entertaining children and pacifying adults with a sweet tooth,” Azad writes in her cookbook, Indo-Pakistani Cuisine. Gulgulay evokes the cocoon of childhood memories; the warmth that comes with round, deep fried desserts. Azad’s cookbook is aptly titled, since it contains recipes eaten by families in the Indian subcontinent before partition divided identities and families, attributing national weight to household foods.

Indo-Pakistani Cuisine is one of many cookbooks included in the Indian Community Cookbook Project, a digitized archive that contains written recipes and community cookbooks written by many authors. Despite the name, though, not all the recipes come from printed books. “Many of India’s recipes live within oral cultures,” says Ananya Pujary, one of the founders of the project. “We wanted to address those. To document cultures at the risk of disappearing, on the brink of forgetting.”

Indian Community Cookbook Project was started by Pujary, Khushi Gupta, and Muskaan Pal in 2019, as part of a digital humanities course at Flame University in Pune, India. “As a generation that lives in sync with the digital world, we thought about what we don’t encounter very much on the internet, what goes missing there.” Pal says. “Handwritten recipes, those passed down through the phone or conversations in the kitchen, are very valuable. And we wanted to preserve them, even to access them ourselves.”

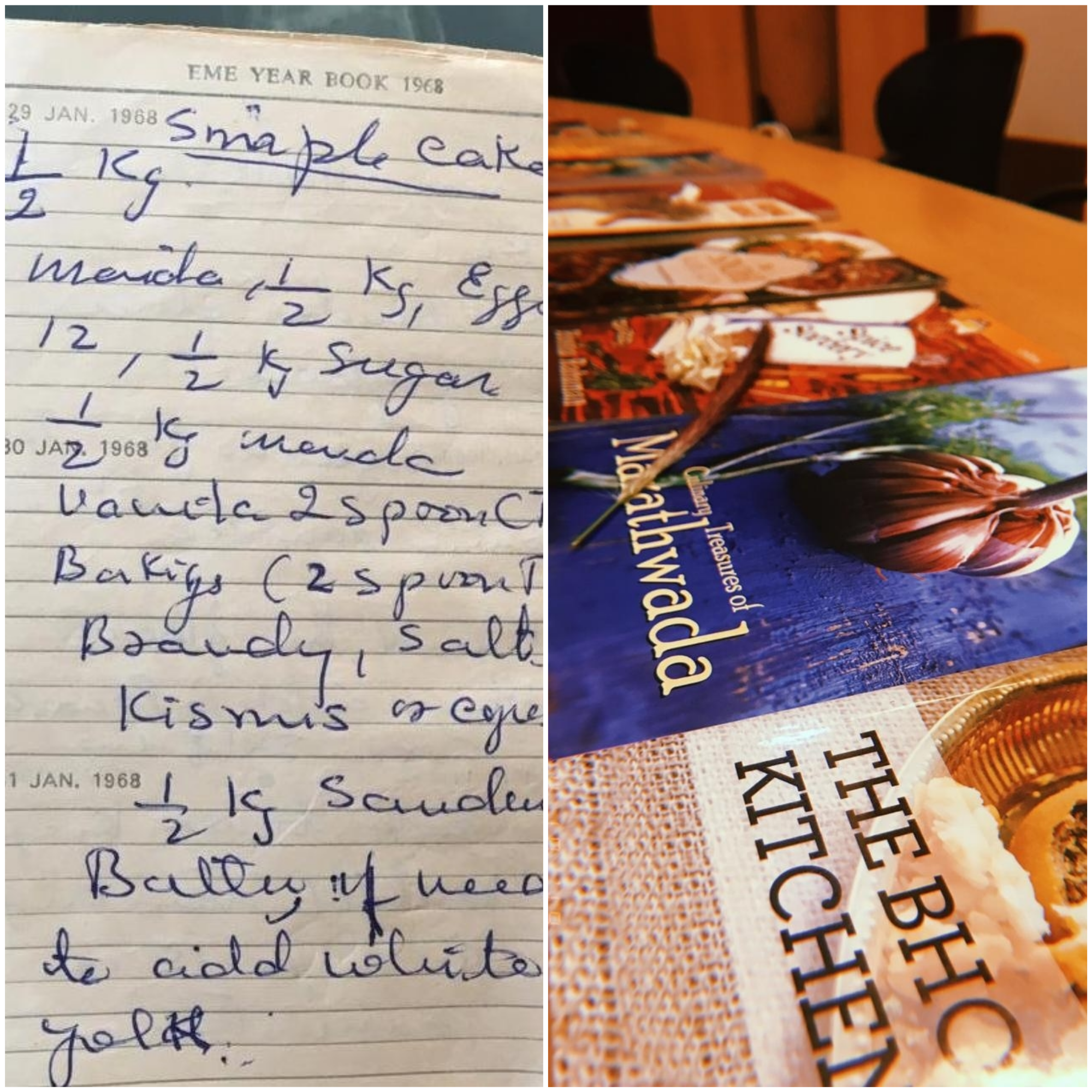

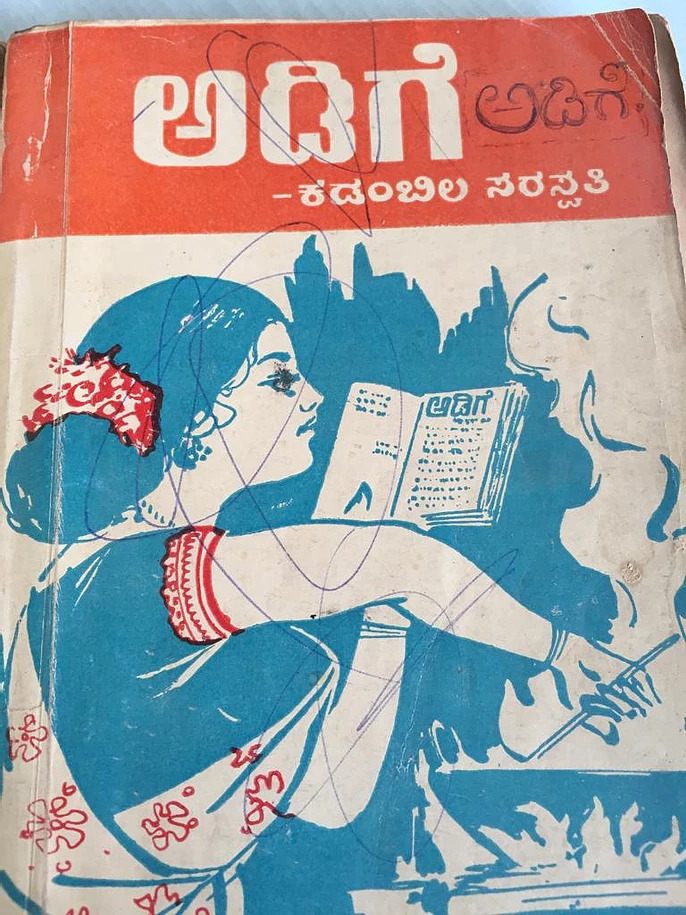

“The tradition of writing down recipes in cookbooks started to flourish after the arrival of the British in India, with the first settlements. British housewives, or memsahibs, compiled cookbooks for Indian cooks and domestic staff who worked in their home. In the late 1800s, regional cookbooks, including the Pak-Shastra in Gujarati and Mistanna Pak in Bengali, began to be published. After the subcontinent gained independence, and with the emergence of more women’s magazines and newspapers, simple, instructional cookbooks were written and circulated amongst women in Indian cities. “But we hope that digitization of small-scale, documented recipes and traditions will expand their reach and scope,” the students say.

The memsahibs’ cookbooks catered to British tastes—their preferences, their formats for meals—but community cookbooks reflected Indian cuisine, and not just traditional cooking. “We found a book that archives only microwave recipes,” Pujary says. “We thought this was interesting, it provides insight into how Indian women moved away from intense kitchen labour, but still maintained domestic balance.” The archive also keeps the original mood of the cookbooks alive, cataloguing the recipes in the author’s original handwriting and voice, and some in audio interviews. “We didn’t want to commodify or gentrify the tone of the cookbooks. It is an archive of cookbooks, but also personalized techniques, measurements, and sentiments that surround foods,” says Pujary.

The students started their research on campus, where they asked classmates and faculty about their home cuisines, which provided access to a large diversity of culinary heritage. Pujary, whose family is from Mangalore, in Karnataka, focused on her family’s contacts, while Pal and Gupta spoke to acquaintances and friends whose cuisines they did not know well. “We found a lack of representation from some cuisines, so we actively looked for people that could help us with those.”

The Covid-19 pandemic and national lockdowns disrupted the team’s work and made in-person interviews impossible, but they turned fruitfully to social media. “With the pandemic, people started paying closer attention to their own traditional and home foods and documenting those on social media,” says Pal. “So we looked for something that stood out, and contacted them.”

The archive also veers away from culinary ownership, which is a rare feat in the documentation of Indian food. Instead of attributing dishes to royal regimes or dominant caste communities, it seeks to highlight individuals or communities, and the variety in the archive is already extensive and democratic: Author Nargis Mithani, for example, contributed Khoja recipes such as Junagadhi kebab (made with minced mutton or keema) and singoli (a sweet, fried dumpling the size of a small fist, made with coconut and poppy seeds). Khoja Cuisine is from a Muslim community in Gujarat, a state with a predominantly Hindu population that polices the foods of minority communities by imposing a hierarchy of vegetarianism. “There is a definite othering of foods and cuisines from marginalized backgrounds, of communities that disrupt nationalist agendas,” says Pal.

The trio gives special mention to the cuisines of India’s Northeast, a region home to hundreds of ethnic and indigenous tribes that face racism and whose cuisines are often dismissed as “smelly” and foreign. The archive contains a recipe for rosup: a Naga stir-fry made with bamboo shoots, dried fish, yams, and the Naga raja mircha, or ghost chili, along with one for pork cooked with axone, a fermented soybean eaten across Nagaland. The use of fermented ingredients in Naga cuisines speaks to food access and the history of foraging and storage, Pal says. “In this way, community cookbooks are cultural artifacts—they can tell us a lot about the lives of women, the market, food scarcity, and the politics of inclusion and exclusion.”

Though hand-written and community cookbooks have a long history in South Asia, many oral cultures, household secrets, and recipes are hidden in cracks. Since Indian food is usually packaged for sale to Western countries, anything unpalatable to those customers remains neglected. But the archive defies a monotone of palate and brims with kitchen-bound secrets and inter-generational wisdom. Along with recipes, the trio hopes to expand their section of “Timelines,” which map the evolution of cookbook cultures, and create other branches of the project, such as a “Food Memories” section for oral histories and stories from their interviewees and collaborators.

“It is a never ending project,” they say. “In South Asian cuisines, within a dish are several dishes, within a cuisine are layers of ingredients, preferences that can change one recipe from the next.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook