The Irish Pigged Out on Pork in a ‘Mammoth’ Iron Age Building

The guests brought swine from far and wide, and left dozens of carcasses behind.

In many of the world’s most memorable holiday traditions, communities gather around a large pile of meat—whether it’s turkey and roast ham, seven kinds of seafood, or haggis to honor the Scottish poet Robert Burns. Recently, scientists analyzed dozens of bones found at the site of a historic Iron Age roundhouse in Ulster, Northern Ireland, and found that pig was the delicacy of the day. They concluded that the porkers had come from far and wide, and had likely fed the guests of an epic provincial feast.

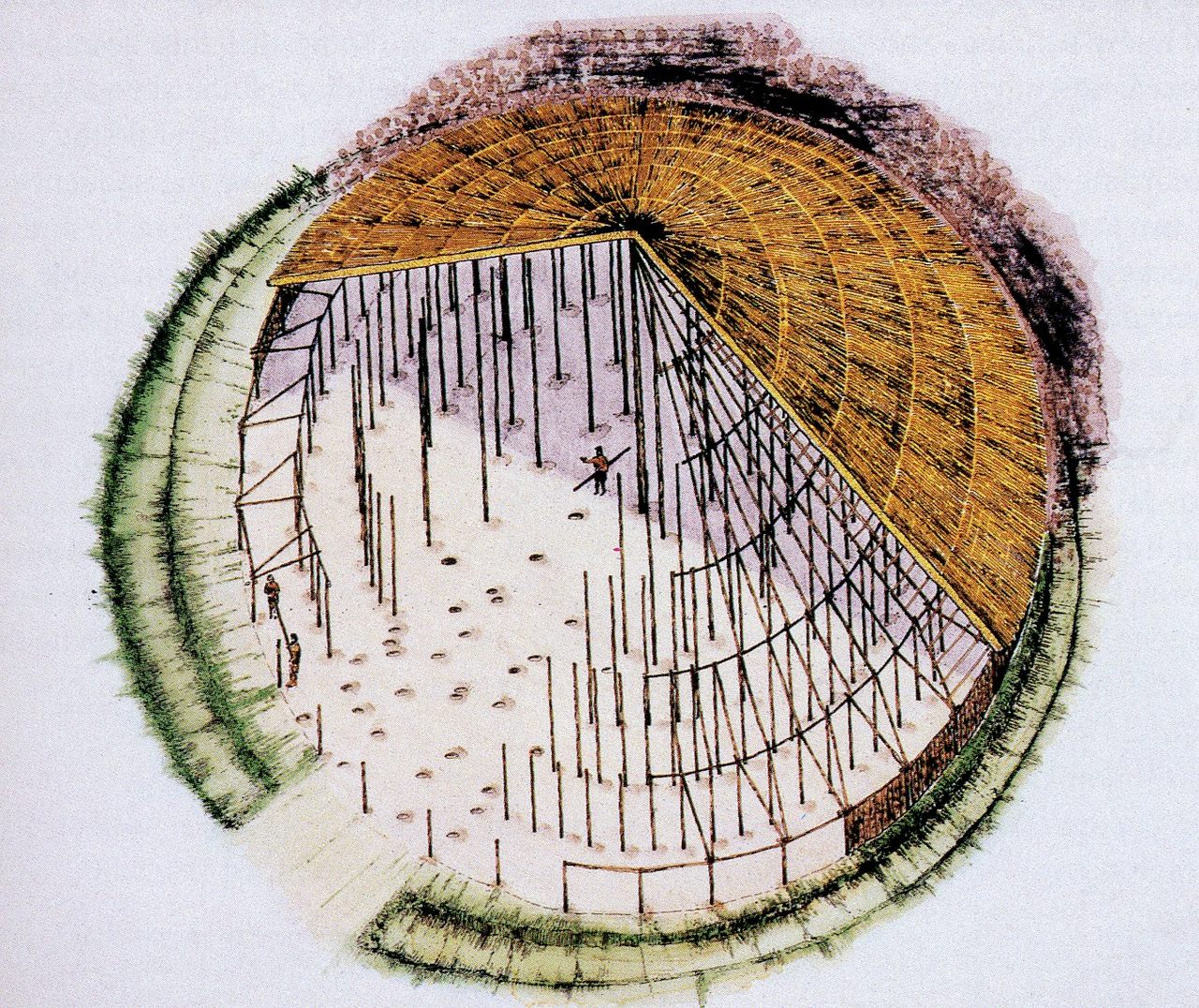

The new research has hinted at a use for the massive circular structure at Navan Fort, which was built on a site that has been settled since the Neolithic Age. “People have suggested it’s a feasting hall,” says Richard Madgwick, an osteoarchaeologist at Cardiff University and a lead author of a new paper that describes the team’s findings in the Nature journal Scientific Reports. “For this period, it would be an absolutely mammoth building. One of the largest that’s known.”

The 1st-century BC roundhouse measures over 130 feet across, and contained the remains of some 35 animals. Madgwick studies feasting in prehistoric Britain, where mega meals offered a means of community bonding—as well as a chance to eat as much as you could, in a gastronomic marathon.

Previously, Madgwick described how ancient Brits schlepped pork to Stonehenge from far-flung parts of the Isles. But the presence of pork at that particular site was less surprising. “Stonehenge differs from this work because Stonehenge’s pigs were raised in an era where pigs were everywhere. It would’ve been way easier,” he says. “That’s not the case for the Iron Age. Pigs are a very peripheral species at the time.”

For the Iron Age feasters of Ulster, pigs were both the meal ticket and the meal. “You had to bring a pig in order to be part of the feast,” Madgwick says. Like the animals found at Stonehenge, the Irish porkers were not raised on the site where they were eaten. Multi-isotope analysis has suggested that the creatures were brought from more rural regions to the provincial capital at Ulster, Navan Fort, as a way of paying tribute to the local seat of power.

It seems that a very different party animal also made it to the feast. Alongside the 34 pig skeletons, excavations uncovered the skull of a Barbary macaque—a monkey from northern Africa. Madgwick says this speaks to the significance of Ulster as a cultural center, one where not only locally-sourced animals were brought, but also creatures from abroad. It’s not known whether the monkey was consumed.

Whether the primate was a mere curiosity or a meal, the pigs were the main event. Madgwick isn’t sure whether they were eaten in one go, or in multiple feasts over a certain period of time, but they couldn’t have lasted too long. “Pig is a fatty meat,” he says. “It goes off quite quickly, and therefore you’d want to feast on it fast, and consume it all.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook