The Man Who Turned His Home Into a ‘Mosaic Palace’

Yossi Lugasi spent decades making portraits of famous people out of smashed ceramics.

Yossi Lugasi was tired during the final months of his life. He had a hard time getting out of bed, moving or eating. His wife, Yaffa, begged him to finish the portrait of Donald Trump he started working on when he was still feeling better. Lugasi would get up, drag himself to his work table, glue some orange, pink and yellow mosaic pieces to a net, and go back to bed.

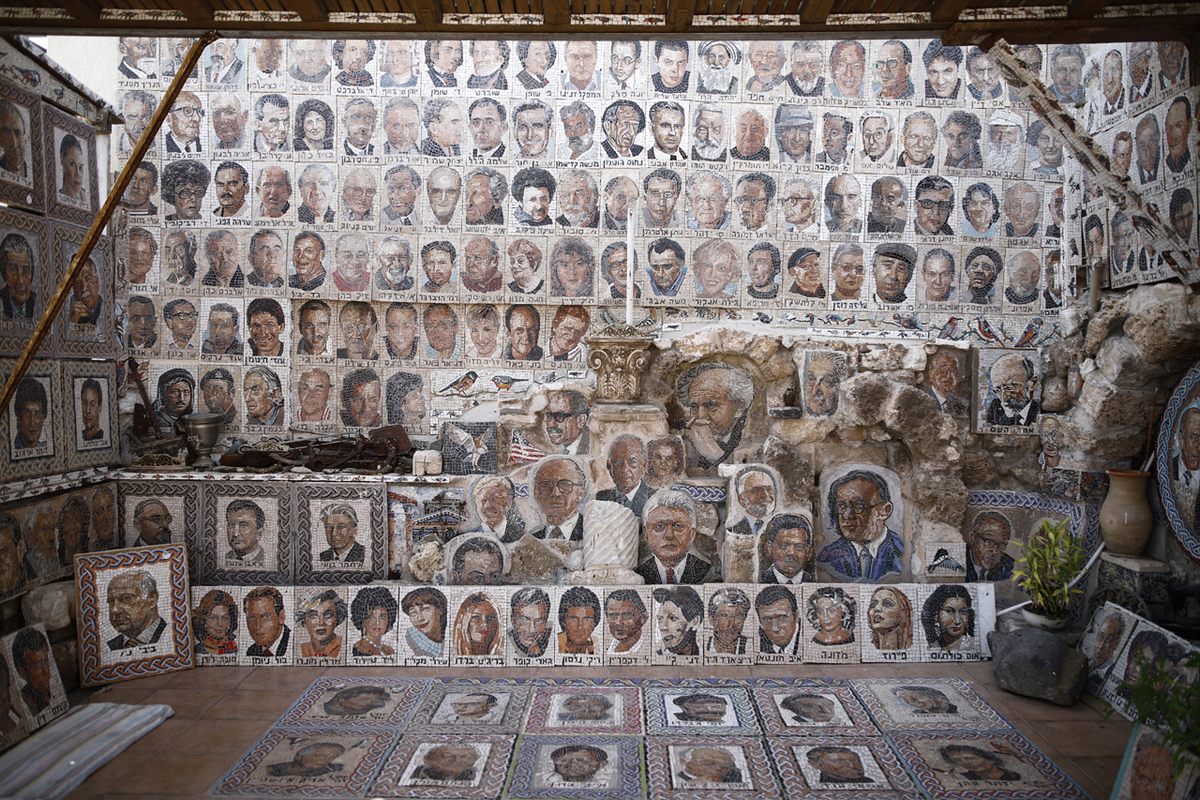

Lugasi passed away a year ago. The small mosaic portrait of Trump hangs in a discreet corner of the living room in his apartment, in the Israeli port city of Jaffa. It is hidden among hundreds of such portraits, mostly of Zionist leaders, Jewish historical figures, and Israeli pop culture icons. The portraits cover the walls, doors, door frames and floors of the humble housing project apartment. They spill out onto the roof: artists and actors, prime ministers, presidents and philosophers, Holocaust martyrs, war heroes, members of failed American peace conferences, and the spy Eli Cohen, portrayed by Sacha Baron Cohen in the Netflix series The Spy. The portraits hang on walls on the roof, overlooking the Jaffa projects, blending into a landscape of solar water heaters and clothes lines.

Over four decades, Lugasi—who left school during the 5th grade, was barely literate and never studied art formally—created no less than 1,090 mosaics.

Yaffa Lugasi, who retired a few years ago from her position as a departmental secretary at the Electric Company, gives tours of her home for a modest fee, which also includes a film about her husband’s life. She says the house is the world’s largest mosaic creation. According to her, the family contacted Guinness World Records to have it included, but was turned away under the pretext that the house belongs in a new category, which Guinness has yet to define.

Yaffa seems to be waiting for her husband to come out of the bedroom and join the tour she gives me and Corinna, my photographer. She met Yossi in 1977, and they had three children together. “Yossi never had a regular job,” she says. “This is how he grew up, outside the establishment. I became the breadwinner and he stayed home to cook. I did this out of love, to give him peace of mind.”

After dropping his children at school, Lugasi would sit down to work in a tiny room at home. He created the mosaics with a technique he developed himself: he made pencil drawings on an insect protection net covered with a special substance. He then glued on the mosaic stones, which were actually bits of tiles, ceramics, and construction waste that he collected and smashed to pieces.

Lugasi was born in Morocco in 1949, to a family of eight siblings. In 1954, during the great immigration of Jews from Islamic countries to Israel, his family arrived at a tent camp for recent immigrants in the Beit She’an Valley. His mother Aliyah worked as a seamstress, and his father Eliyahu painted houses. Lugasi’s workroom features a murky oil painting of a hill covered with tents. At the front of the painting a woman sits on a pile of suitcases, watching children playing in the mud.

I imagine little Lugasi, wet and shivering in a rainwater-soaked tent. Avi Lugasi, his son, interrupts my fantasy of romanticized poverty. “This is not a sad painting,” he laughs. “A child doesn’t feel poor. He tells himself: ‘My parents have a harsh, complicated life, but that’s not my problem. I’m happy. I have a puddle of mud.’” But in 1963, the hardship and the alienation became too much, and the Lugasis moved to Jaffa. “Jaffa reminded them of Casablanca: a town with mixed population, sea, fishing,” Avi says. Lugasi dedicated one of his Jaffa apartment roof walls, not far from the Ashkenazi Holocaust hero portraits, to Arab music stars. “He had Arab friends and he wanted for them to have reason to come to the museum,” his son explains.

Jaffa was not an easy place to live in. Lugasi left school during the 5th grade and went to work. “One day he passed by the grocer, stole some food, got caught and was taken to the Welfare Office,” Yaffa says. “A social worker who was talking to him gave him a pencil and a paper, and he began to draw.” He never stopped.

“He would walk on foot from Jaffa to Tel Aviv and stand for hours in front of an art supplies store just to ‘fill up’,” with inspiration, Yaffa says. When he turned 13, as a bar mitzvah present, he went to visit his friends from the absorption camp back in the 1950s. The friends had moved to the poor ‘“development town” of Beit She’an. The camp was razed, and beneath it were found the remains of the grand Roman and Byzantine city Scythopolis and its many mosaics. As an adult, when he couldn’t find a place to store drawings that were vulnerable to the rain and sun, Lugasi chose as his medium the eternal mosaic, which, like in Scythopolis, never peels or fades.

Today, impossible meetings occur on Lugasi’s roof, under the strong Jaffa sun: Ben Gurion is watching Clinton and Elvis is staring at Itzhak Rabin. One could expect Lugasi to reject those people, the representatives of an establishment that marginalized him. Avi says his father did the exact opposite: He built a shrine to them, and so reclaimed power. “His creation,” Avi says, “complements his life story.”

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook