The Art of James Castle, Created With Spit, Scraps, and Soot

He hid his sketches, made with DIY supplies, in the nooks and crannies of the family home.

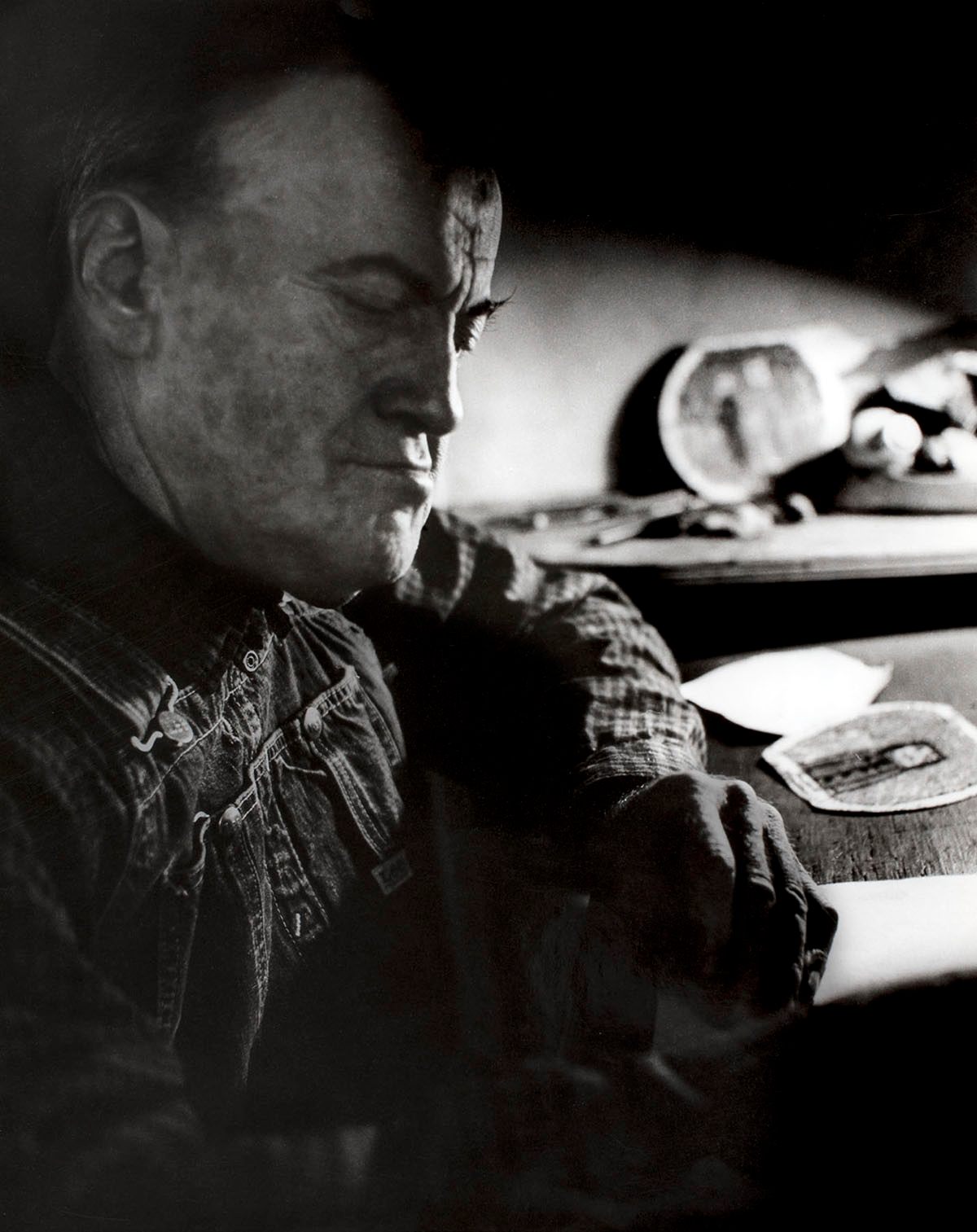

At the outskirts of Boise, Idaho, in a subdivision of modest homes on neat lawn rectangles, the deaf-mute artist James Castle (1899-1977) used handmade art supplies to sketch his surroundings. He lived in a bungalow with half a dozen family members, who took care of him as he diligently worked on drawings in the property’s tarpapered shed and clapboarded trailer.

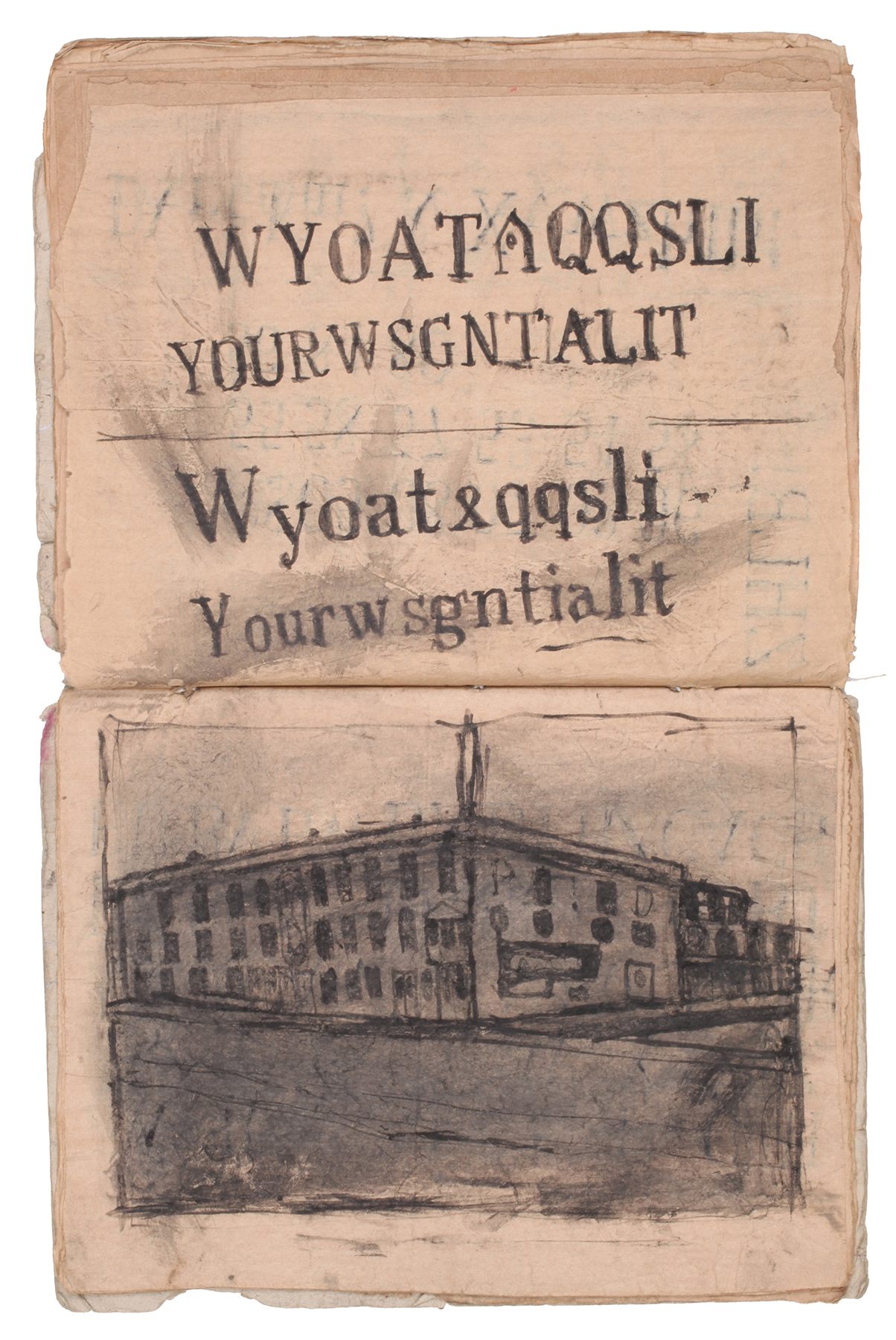

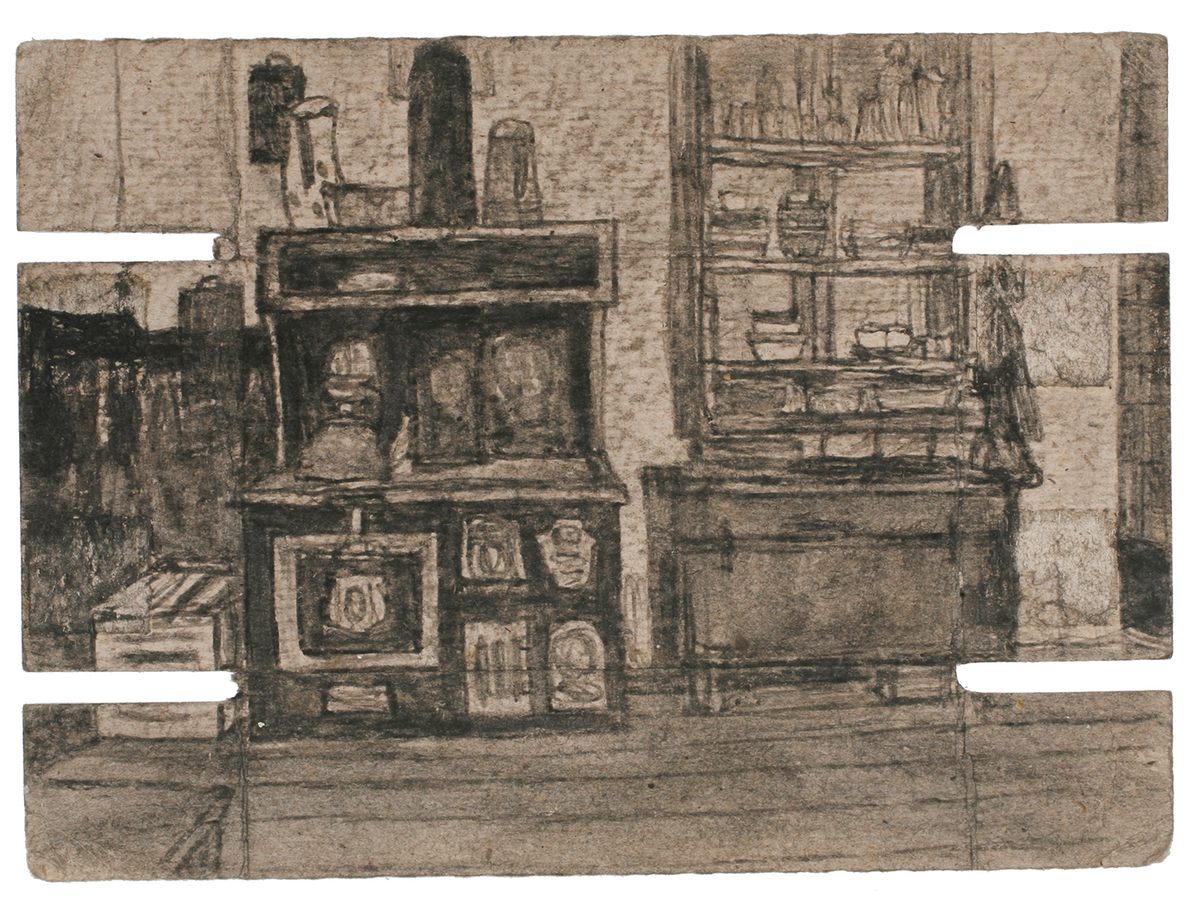

To create dark pigments, he mixed stove soot with saliva. On paper scraps, he captured even the details of doorknobs, windowsills, washbasins and framed portraits of ancestors. Over the years, he tucked batches of his drawings into crannies around the house and the outbuildings.

Castle memorabilia has been surfacing from within the walls, floorboards, gardens, and lawns, as the Boise compound has undergone recent renovations. “We think we’ve found it all and then something else comes up,” says Rachel Reichert, the cultural sites manager for the Boise government’s department of arts and history. Her team is now converting the property into a city-owned cultural center called the James Castle House. It is due to open in the spring, and the public will also be welcomed at the nearby James Castle Collection and Archive, which owns thousands of his works and fosters scholarship.

Craftspeople and historians at the artist’s home are now protecting and documenting every vintage nail, excavated bottle shard and speck of wallpaper, the kinds of mundane materials that appear so often in Castle’s sketches. “I love the poetry, the interesting conversation between the buildings and the artwork,” Reichert says.

Castle grew up with almost no exposure to mainstream art. His parents worked as postmasters, farmers and storekeepers. Around age 10 he was sent to a government-run boarding school for the deaf, where he spent five years. He remained nonverbal and largely illiterate. But he “was always busy looking and busy doing,” one of his relatives reminisced in the 1990s to Jacqueline Crist, the managing partner of the Castle Collection and Archive.

Castle would typically begin his days by leafing through the newspaper—he particularly liked the comics—and then he would focus on making art. Food packaging, matchbooks, greeting cards and old homework assignments—any kind of paper that the family did not want, he would recycle. He sometimes sketched the same rooms and objects from numerous vantage points; he was apparently orienting himself, and organizing his impressions, in a soundless world.

He set up numerous mini-exhibits at home for his own enjoyment. Once he finished tacking up his drawings all around a room, he would sketch his own crowded displays on yet more sheets of scrap paper. The family sold some of his works in his lifetime, and he was persuaded to lend pieces to a handful of galleries and museums in Boise and as far away as Seattle. At the Boise house, anyone who appreciated his art would be shown more the next time they stopped by. People who were not impressed, however, would be snubbed ever afterwards.

In 1977, Castle sketched self-portraits while he was dying in a Boise hospital. He depicted himself in bed, eyes closed, and he detailed the adjacent window’s dark frame, the bunched curtains, the unwatched TV mounted on the ceiling.

The city is now adapting his family’s formerly crumbling structures into spaces for exhibitions, events and artists’ residencies. Fixtures like sinks and ceiling lights will be modeled after rustic pieces shown in his drawings, and some of the furnishings will be antiques with a patina of wear. “We want to tone down that shine of new construction,” Reichert says.

The renovation process has revealed how the Castles had thriftily redecorated and added a few rooms over the years. The family built with their own hands, without removing much that was already there. “It’s kind of a layer cake, which is great,” says Byron W. Folwell, the project architect and exhibits designer. Wallpaper fragments survive, along with some scraps of clothing were inexplicably slathered on the walls. The family’s favorite patterns in wall coverings included stripes, florals, sailboats, curlicues and clouds.

In some rooms where James Castle had tucked his artwork into crannies, mice and moisture eventually wreaked havoc. An unknown number of his drawings ended up reduced to powder over the years. So some of the very dust wadded into the buildings’ timbers is made up of ruined drawings. “Parts of Castle’s works,” Reichert says, “forever will remain encased here.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook