For Sale: Jane Austen’s Wince-Inducing Descriptions of 19th-Century Dentistry

In a letter to her sister, the novelist politely recounts a grisly scene.

After dinner one evening in September 1813, Jane Austen sat down to write a letter to her sister Cassandra. Austen, who had published Pride and Prejudice earlier that year, had much to report from the home front. She had accompanied three nieces and her brother Edward to a Wedgewood china shop, she wrote, where they’d perused the wares. Other news was less pleasant: Earlier that day, they’d been to the dentist for an hour of “sharp hasty screams.”

“The poor Girls & their Teeth!” Austen wrote. “Lizzy’s were filed & lamented over again & poor Marianne had two taken out after all.” The dentist—a Mr. Spence, who could have been one of several Spences working as dentists at the time—had even gone after her niece Fanny’s teeth, though they had seemed in decent shape. “Pretty as they are,” Austen recounted, the dentist had “found something to do them, putting in gold & talking gravely.” That didn’t sit right with Austen, who wrote that the tool-happy man “must be a Lover of Teeth & Money & Mischief.” Austen remarked that she “would not have had him look at mine for a shilling a tooth & double it.” Her note, which is going under the hammer at Bonhams on October 23, is an intriguing (if squirm-inducing) dispatch from an era of grisly dental work.

At the time Austen penned the letter, dentistry was still painfully unstandardized. Treatments varied widely, and troublesome teeth were often yanked out by people from all sorts of professions. “In London and large towns, surgeons were available to pull out teeth, but elsewhere, apothecaries, quack tooth-drawers, and even blacksmiths might oblige,” write historians Roy Adkins and Lesley Adkins in Jane Austen’s England: Daily Life in the Georgian and Regency Periods.

Austen’s reference to filings in the letter “shows the diversity of practice because of the lack of scientific understanding of the causes of decay,” explains Rachel Bairsto, head of museum services at the British Dental Association Museum, in an email. There was a lot of disagreement about whether various interventions would offer the patient relief, or just plunge them deeper into pain. Though filing had historically been used to smooth out uneven teeth, Bairsto adds, some practitioners recommended it as a way to prevent cavities. Others disagreed, arguing that it “made more space to trap food.” In any event, Bairsto writes, “overzealous filing could make the teeth more sensitive.”

Even where tooth-pullers and oral hygiene tools were available—and it was mostly the wealthy who could access them—they weren’t necessarily a good idea. “Early toothbrushes with their horsehair bristles often caused more problems than they prevented,” writes medical historian Lindsey Fitzharris in The Guardian. “Toothpastes or powders made from pulverised charcoal, chalk, brick or salt were more harmful than helpful.” Eighteenth- and 19-century animal-hair bristles were breeding grounds for bacteria, which could make any existing mouth trouble even gnarlier.

Though holes in teeth were sometimes patched, fillings “were not commonly practiced, as they were expensive and often didn’t last long,” Bairsto writes. Extraction was the more common, and decidedly miserable, route. An extraction was often accomplished with the help of a dental key (also called a tooth key), which Bairsto describes as “rather a fearsome-looking instrument.” It’s a nightmarish claw-and-rod contraption, and it would have been wielded without anesthetic. Bleeding and infection often followed.

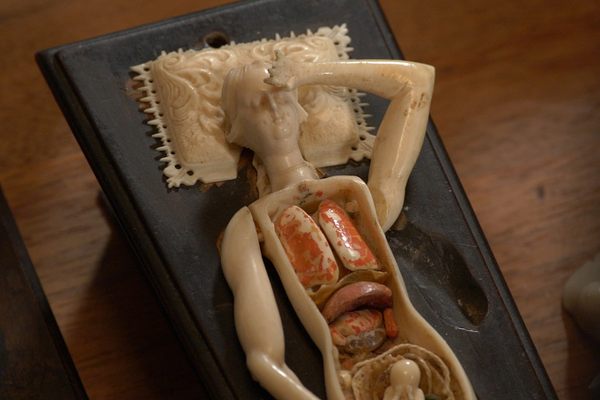

Once the infected incisors or meddlesome molars were out, they would sometimes be replaced with dentures, which could be made from walrus or hippo ivory, porcelain, or teeth removed from other unfortunate people, living or dead. (When the Battle of Waterloo felled thousands of soldiers, “clients back in England were happy to wear dentures made from the teeth of fit young men killed in battle, which became known as ‘Waterloo teeth,’ or, more coyly, ‘Waterloo ivory,’” Adkins and Adkins note.) Dentures weren’t without their drawbacks, Bairsto writes: They had a tendency to stink and rot in the mouth, “and the use of a fan was required to waft the stench.”

By the middle of the 19th century, the world’s first dental school had opened in Baltimore, Maryland, Collectors’ Weekly reported, and across the pond, Queen Victoria had helped make it fashionable to own a personal set of dental tools. Her scalers—tools used to scrape off gunk—were outfitted with mother-of-pearl handles and gold detailing. That was of no help to Austen.

Because oral hygiene was expensive, Bairsto writes, “it is unclear” whether the Austens routinely used toothbrushes. For the most part, writes historian and Austen biographer Lucy Worsley in Jane Austen at Home, “Jane and her family simply had to put up with the small aches and ailments of life.” Even so, references to dentistry—and the anxiety that a visit to a dentist might incite—appear in some of the writer’s fiction. In Emma, Harriet has “a tooth amiss,” and is reported to appear a bit “out of spirits.” That’s “perfectly natural,” readers are told, “as there was a dentist to be consulted.” In Austen’s realm, even fictional characters knew that a visit to a dentist could sour an afternoon.

Janeites are a devoted bunch—the sight of her writing table, at the Jane Austen’s House Museum in Chawton, England, often prompts rapt reverence, or even tears—and the letter is likely to be catnip for her most enthusiastic reader-disciples. (Bonhams expects the letter to sell for somewhere between $80,000 and $120,000.) For everyone else, it’s a macabre memento from a time when the sharp end of a dentist’s tool was a place you really, truly did not want to be.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook