An Island’s Spiritual History, Documented in Haunting Photographs

Walking the trails to prayer on Japan’s Nozaki Island, once home to persecuted Christians.

One day in October 2016, a small boat approached the dock at Nozaki Island, Japan. Among its passengers was a photographer, Makiko. She had traveled from Fukuoka, via neighboring Ojika Island, with her Leica M Monochrom camera and enough packed in her luggage for a two-day stay. She had one purpose in mind: to walk the trails that the island’s persecuted Christians had walked, in secret, centuries before.

Nozaki Island, off the country’s southwest coast, consists of 2.8 square miles of mountainous terrain and forest. Today it is home to wild boar, deer, and Japanese wood pigeons, but early in the 19th century, it was a safe haven for Japan’s kakure kirishitan—“Hidden Christians”—who could not practice their faith openly.

“Christianity was introduced in mid-16th century in Japan, but between the 17th and late 19th centuries, it was banned by the government,” says Makiko, who goes only by a single name. Basque missionary Francis Xavier brought the religion to Japan in 1549, but as it grew, so did Japanese fears of influence from external powers. In the late 1500s, ruler Toyotomi Hideyoshi expelled all missionaries, and between 1612 and 1614, the Tokugawa shogunate banned Christianity outright. Christians were forced to practice their faith in secret. If discovered, they faced torture or death. Some fled for more remote locations, such as Nozaki Island.

“For centuries, there was a Shintoist community having self-sufficient lifestyle with agriculture and fishing” on the island, says Makiko. “The first two hidden Christian families arrived from Omura early 19th century.” These two families are believed to have founded the Nokubi settlement, one of two Christian communities on the island. Following this, the photographer says, “three hidden Christians hid themselves under the commercial goods in the bottom of the merchant’s boat, escaping from execution, and settled in the Funamori community.” The Nokubi and Funamori residents used a mountain trail, called Satomichi, to reach mass.

On the day when she arrived on the island, Makiko noticed the remnants of the Shinto community right away—“ghosty-looking houses”—and began her trek on the island’s trails. During one walk, she realized she wasn’t alone. One of the island’s deer saw her approach and, “after walking for a long time through tunnels of camellia trees, when I reached the ground covered with wild ferns, it emerged in the wild forest.” The island has approximately 400 wild deer. “I felt constantly watched by them,” she recalls.

The ban on Christianity was lifted not long after the Meiji Restoration in 1868. “Within 10 years after the Japanese government abolished the law to ban Christianity, they [the hidden Christians] managed to build their own churches in Funamori and Nokubi communities,” says Makiko. “In its peak years—the mid 1950s to 1960s—there were about 680 inhabitants living on the island in these three communities. The island was gradually abandoned due to rapid economic growth on the mainland, and both communities moved out for modernized life.” According to the photographer, the island’s last inhabitant was a Shinto priest, who left in 2001.

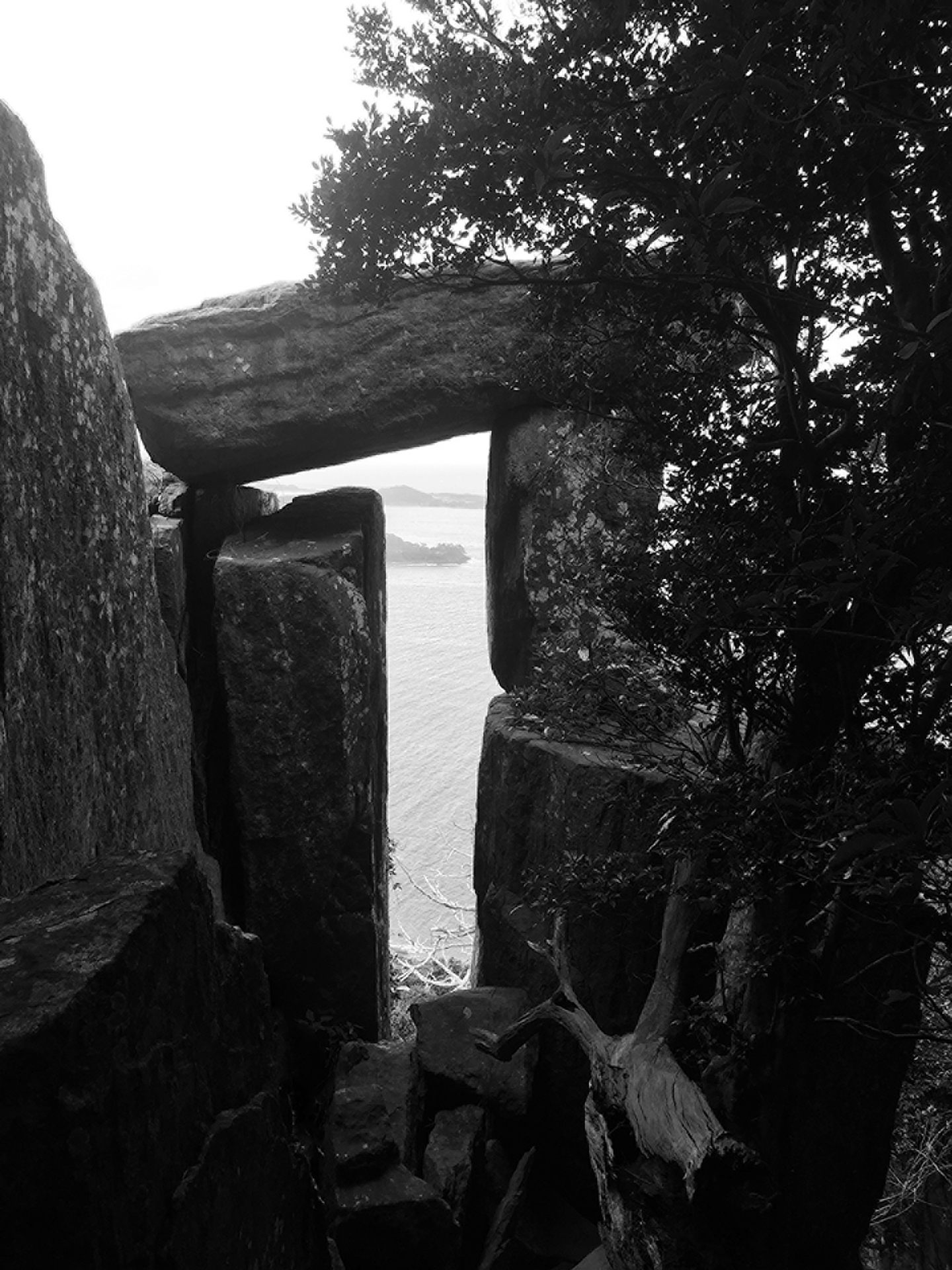

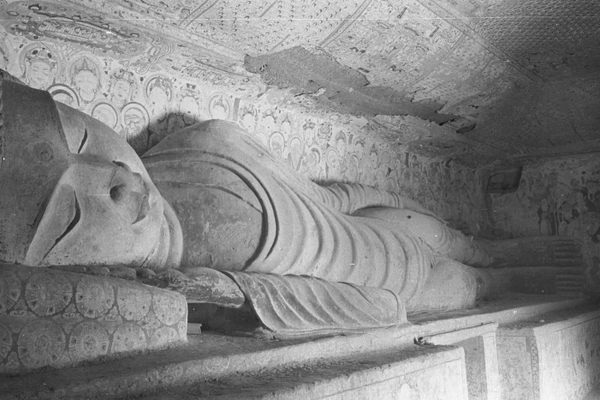

The Nokubi Church is no longer operational, but can be visited by appointment. The Shinto shrine, dating from 704, is still standing, and there are remains of a terraced field and a school at Funamori, as well as a prehistoric stone structure some 80 feet high. Makiko describes her visit as a “spiritual experience,” which comes through in her black-and-white photographs. The island appears almost otherworldly. Shadowy tunnels of trees wrap around a worn pathway, an exposed, windswept coastline crumbles into the water, a deer watches thoughtfully through a veil of dense forest.

Atlas Obscura has a selection of images from Makiko’s series, called Trails to Prayer.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook