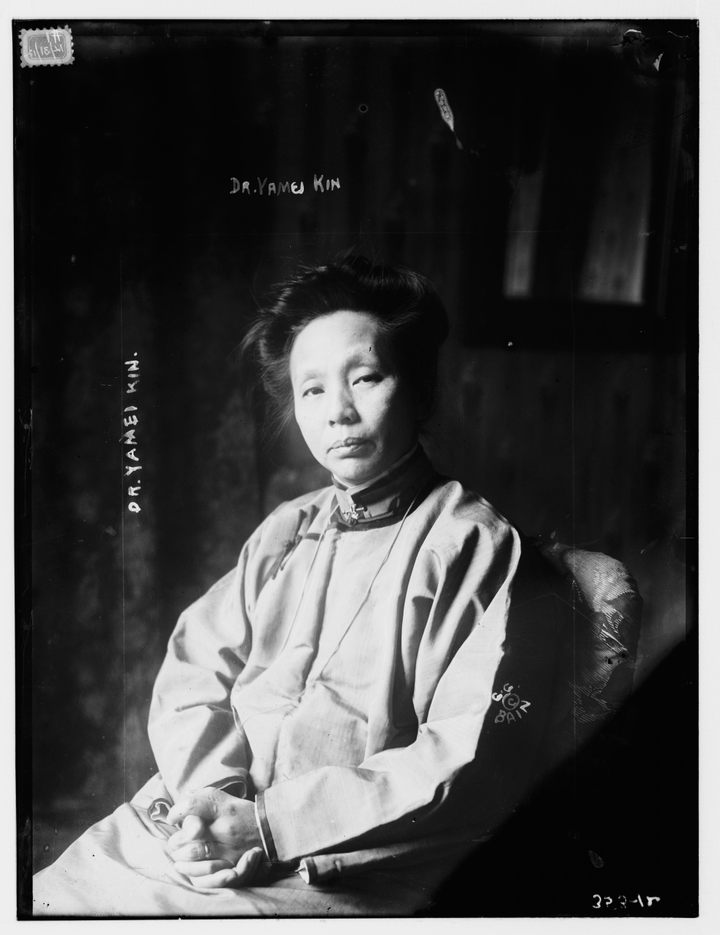

Meet America’s Godmother of Tofu

A century ago, Dr. Kin Yamei broke ground trying to popularize tofu. The nation’s tastes have finally caught up.

In the summer of 1918, the kitchen on the top floor of 641 Washington Street in New York City was filled with buckets of cream-colored slurry. Pails sat next to the stove; jars and bottles of the liquid lined the shelves. It looked as if someone had just milked a herd of cows.

But this “milk” did not come from any animal. All of it was soy milk.

“I might talk to you until doomsday about the manifold uses of soybeans, but you wouldn’t understand,” Dr. Kin Yamei told a reporter for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch visiting her laboratory, which was operated by the United States Department of Agriculture. She had just returned from a six-month mission to China on behalf of the U.S. government.

The American government feared World War I would deprive soldiers and the American public of constitution-fortifying meat. They tasked Kin with researching the soybean’s varied applications in China as an alternative. Kin was well aware of this little legume’s potential. She knew that, if you curdled its milk long enough, it would clot into a protein-rich cushion called tofu.

The word “tofu” hadn’t yet entered American vernacular. Kin often described it as a “vegetable cheese” to a public that considered soybeans inedible pebbles. In the early 20th century, said public held deep prejudice towards both Chinese cooking and Chinese people. The American government at the time still rigorously enforced the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which barred Chinese-born laborers from entering the country.

To Kin, the soybean was a nutritional miracle, possessing the benefits of meat and milk without its drawbacks. But despite her passion, Kin’s efforts just didn’t take. Those predicted wartime shortages didn’t come to pass, and American attitudes towards Chinese people also muffled her message. She died in China, in 1934, without seeing the fruits of her advocacy blossom in America.

Only in the last five years has Kin gained greater attention, with features in the New York Times and America’s Test Kitchen presenting her as a woman ahead of her time. A century later, America has finally started to embrace her message.

Kin spent her life torn between two countries. Born in the Chinese city of Ningbo in 1864, she was only two when she lost her biological parents to a cholera epidemic. A pair of white American Protestant medical missionaries adopted her, raising her between China, America, and Japan. Around 1880, she began medical school at the Women’s Medical College of the New York Infirmary at age 16. She enrolled there as Y. May King, likely to conceal her racial origins. This was two years before the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act. The senator who introduced the law called Chinese people a “degraded and inferior race,” while others who supported it referred to them as “rats,” “beasts,” and “swine.”

This climate of intolerance infected Kin’s day-to-day life. Workmen would pelt her with insults when she walked outside. Her classmates treated her with antagonism. While in school, Kin boarded with a fellow immigrant from India whose religious credo forbade her from eating meat. The writer Jaroslav Průšek, a Czech Sinologist and translator, befriended Kin later in life. In his 1940 autobiography, he wrote that Kin told him that her roommate eventually died of starvation. Kin knew from an early age that the United States was unfriendly to vegetarians.

Kin’s graduation from university reportedly made her the first Chinese woman to obtain a medical degree in the United States, a rebuke of the racism of the era. But discrimination dogged her in the years that followed. She encountered venomous anti-Chinese sentiment as a medical missionary in China from her peers, while her advisor declined to provide lodging because she was a woman.

Dejected, she sought refuge in Japan, where she practiced medicine for several years. There, she met a mustachioed musician named Hippolytus Laesola Amador Eça da Silva and married him in 1894. Though their marriage soured and eventually led to divorce, she doted on their son, Alexander.

In the early 1900s, Kin reinvented herself. Traveling across the United States, she became a celebrity of the speaking circuit, enthralling crowds with lectures about Chinese culture. She often wore Chinese fashions while speaking, while her flawless elocution and commanding mien dispelled any racist presumptions from her audiences. Reporters often didn’t know what to make of Kin, this being who toggled so fluidly between cultures with her “puzzling blend of eastern looks and western speech,” as one journalist for the Leader, a newspaper in Canada (now the Regina Leader-Post), put it.

On occasion, her speeches turned to the beauty of China’s food. She regaled her audiences with cooking demonstrations for chop suey, the riot of meat, vegetables, and sauce most commonly associated with Chinese cooking in America at that point. She also spoke of what she called bean cake—tofu—and described how it was cooked in China.

Even if few Americans knew of tofu at that point, its place within Chinese cooking tradition was well-established, stretching back centuries, if not millennia. There are competing theories about tofu’s origins. One legend even attributes its invention to the ancient philosopher-prince Liu An, who ruled a kingdom in northern China starting in 164 BC. The first written mention of dòufu (豆腐, or bean curd) dates to the year 965, when a document called it the “vice mayor’s mutton,” relating how a poor vice mayor who could not afford meat had to make do with tofu instead.

The food spread to Japan not long after (the exact date of its migration is, again, a matter of dispute). Tofu was first mentioned in Japanese writing in 1182, and the Japanese pronunciation for the food was one of many that Americans used during Kin’s lifetime, alongside “bean curd,” “soybean curd,” and “soy cheese.”

As Kin continued delivering these addresses, the world around her was changing. In 1911, the Qing Dynasty collapsed, and in 1912, China became a republic. In 1917, the United States entered World War I. It was then that the USDA identified Kin as an ideal evangelist for the soybean, due to her fame and spellbinding lectures. Kin embarked for China in the spring of 1917, roaming around the country and collecting soybean samples for the USDA.

Kin underwent this grueling journey despite being denied American citizenship. Nevertheless, she felt a patriotic pull towards the United States, especially since her son was fighting in the war on America’s behalf. “My boy is at the front doing his bit,” she told one reporter. “I want to do mine, too.”

On her return to New York, she set up shop at the USDA’s Washington Street lab and experimented with various treatments of tofu. Others from nearby laboratories would pop their heads in, jonesing for a taste of “soy bean cheese.” One of them fried it with the same gravy in which he’d cooked fish; the curd crisped up so convincingly that he couldn’t distinguish the animal from the bean. “It has a way of absorbing the flavor of whatever it’s cooked with,” the dazzled man told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch journalist. Kin would invite reporters over to her nearby apartment, too, where a hired Chinese cook would chop tofu up and mix it with onions, celery, and chicken stock before cramming it into green peppers. Unsuspecting diners were delighted: They just couldn’t believe that what they were eating wasn’t meat.

For Kin, cooking was a source of wonder and an outlet for creativity. But she believed American cuisine was in dire need of both. “American women, you must admit, are lacking in artistic sense,” she said bluntly to that St. Louis Post-Dispatch reporter. “That is because the country is so young. When the process of refinement is farther advanced they will not regard household work, especially cooking, as drudgery. It really is art.” She felt that tofu’s adoption amongst Americans could break the monotony of a staid plate of pork and beans.

Kin wasn’t vegetarian herself, but she found joy in not consuming “what was once a palpitating little animal, filled with the joy of life,” she continued to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. China has a a long tradition of vegetable-forward dining, and she told American cooks how tofu could mix nicely with beef, chicken, or ham. But Kin also knew that tofu could completely replace animal products if home cooks so desired. “It has all the advantages and none of the faults of animal cheese,” Kin said to another paper.

Prior to Kin, “mainstream American awareness of tofu was pretty nonexistent,” says Matthew D. Roth, author of Magic Bean: The Rise of Soy in America. Those who consumed it lived on the fringes. Some small shops frequented by Asian American communities made it fresh, while home economists and Seventh-day Adventists who’d gone to Asia on missions were clearly aware of it. But American incuriosity, particularly when it came to Chinese cooking, was stubborn.

To work against that ingrained disinterest, Kin poured her energies into proselytizing tofu through as many avenues as possible. She corralled the press into her laboratory and kitchen to show them the wonders of tofu. She traveled up and down the East Coast, holding demonstrations and lectures along the way. But her crusade was constantly met with indifference and logistical roadblocks. She tried to persuade the National Canners’ Association, a trade group, to offer soybean dishes to sell on the American market. According to Roth’s book, there’s no sign that the organization ever responded to that plea. Kin also wanted to arrange large-scale tofu meals for soldiers in nearby camps, only to find that shipping soybeans in bulk from the nearest farm that grew them, in North Carolina, was far too cumbersome.

Ultimately, Kin’s project failed. Convincing Americans to embrace tofu at the dawn of the Jazz Age may have been too big an ask, Roth says, though xenophobia isn’t the sole factor that felled her efforts. “I would say that it’s fair to assess her attempt as a failure,” Roth says. “There were several reasons that the time wasn’t ripe. A big factor was that soybeans were not yet a widespread American crop.” In addition to Kin’s trouble with sourcing soybeans, Roth clarifies that wartime rationing ended up being brief. In the end, meat remained cheap and easy to come by.

Funding for her project soon got slashed, and personal tragedy struck Kin just before the war’s end: Her son died while fighting in France. Kin couldn’t make sense of this loss. “What did he die for?” she later asked Průšek, the Czech Sinologist. “What did we have to do with that sickening war?” In the wake of this catastrophe, Kin lost faith in the American project and left for the comforts of China.

Though she dabbled in food—she contributed recipes to community cookbooks in China, for example—Kin’s years in Beijing were spent as a high society matriarch, often hosting younger people like Průšek for dinner parties. A bout with pneumonia killed her in early 1934, when she was 70. She asked that her body be buried on a farm in Haidian, in northwest Beijing. “Here my dust will blend with soil,” she said to Průšek. “And after the pile of clay they will place upon my grave has crumbled as well, I will become a field, a fertile field.”

In the decades that followed, the cultural tide began to shift. The passage of the Magnuson Act in 1943 effectively repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act, establishing quotas for the entry of Chinese immigrants to America. Subsequent immigration laws after World War II—namely 1965’s Hart-Celler Act, which did away with mandates about national origins—helped soften public hostility to Chinese immigrants and, in turn, their food.

By the 1960s, Roth says, American soybeans were widely available for anyone who wanted to make their own tofu. Meanwhile, demand for tofu amongst growing Asian American communities, particularly in California, led to factories who produced it purely for those markets. Tofu also began to appear in grocery stores across the state.

Chinese cookbooks from major publishing houses, such as 1962’s The Pleasures of Chinese Cooking by Grace Zia Chu, helped demolish the stereotypes that had defined Chinese cooking in America. But it was the work of other cookbooks that really shepherded tofu beyond Asian American communities. The groundbreaking 1971 publication of Frances Moore Lappé’s Diet for a Small Planet advocated for plant-based eating as both an individual and public good. It also contained recipes such as tofu sautéed with spinach.

If you grew up with hippie parents (or were a hippie yourself), this might not sound terribly surprising. “Tofu was never an important food in America until the hippies came along,” says William Shurtleff. Shurtleff and his former wife Akiko Aoyagi are the founders of the Soy Info Center, which bills itself as the world’s foremost repository of soybean knowledge. He and Aoyagi bear as much responsibility for ushering tofu to a wider audience in the later 20th century as Lappé: They co-wrote The Book of Tofu, a 1975 introduction to this food.

Word got around that eating tofu could lower cholesterol, giving it a health-food shine. (More recent studies show that it can, marginally.) Yet that promise, along with tofu’s vegan ingredients, made it appealing to younger Americans in the 1970s. “Many people during that period were vegetarians, and some were even vegans,” Shurtleff says. “And so it fit nicely into desires for foods that people had, and met those desires in a nice way. As this demand grew, the number of tofu companies grew.”

Tofu was especially alluring to political progressives during the era of civil rights activism and anti-Vietnam War demonstrations, Roth adds. “The counterculture embraced tofu for a number of reasons: many were exploring Buddhism, non-violence, and vegetarianism, and tofu—replacing blood with water, so to speak—appealed to these sensibilities,” Roth says. “From an anti-war perspective, eating Asian food demonstrated solidarity with the Vietnamese and others being killed and bombed in an American imperialist war.”

But as tofu inched into the mainstream diet, it gained a grim reputation as tasteless health food. Many non-Asian cooks had no idea how to cook it. A century since Kin’s work, tofu still faces a struggle for respect from casual American cooks who might misread it as a lifeless, waterlogged pillow. These are prejudices that Hetty McKinnon, the author of Tenderheart: A Cookbook About Vegetables and Unbreakable Family Bonds, finds herself running up against. “Growing up in a Cantonese household, tofu was an everyday food, as foundational to my mother’s cooking as meat or vegetables,” the Australian-born McKinnon says. Her mother would steam tofu and serve it with cilantro and mushroom gravy, whose flavors spotlighted tofu’s innate creaminess and silkiness.

McKinnon has occasionally been frustrated by what she calls the “whitewashed” mainstreaming of tofu. “In the West, the concept of tofu is still quite narrow and I still often encounter the “bland” and “tasteless” stereotypes,” McKinnon says. She also hears grousing about its so-called “rubbery” texture. “My response to this is clear and emphatic,” she says. “If you have eaten tofu that is bland, tasteless or rubbery, it is because it wasn’t cooked properly.” McKinnon also wonders if the distorted impression of tofu as a mere protein might limit it in the American culinary mind. “In Chinese cooking, we don’t think of tofu or meat as “protein,” but rather as textural elements that add to the final dish,” she says.

These are words one can imagine Dr. Kin Yamei would’ve said herself a century ago, when she wanted Americans to honor tofu in all its forms and uses: As a meat replacement for cooks who wanted to be gentler to their bodies and the planet, as well as an ingredient for eaters who wanted to expand their palates and their minds. “I shouldn’t be surprised if the soy bean will save the lives of many American animals,” Kin said to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Tofu, Kin knew, could do anything.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook