In Samoa, Hot Chocolate Is Homegrown

Growing, grinding, and drinking koko Sāmoa brings families together.

It’s a humid night in Upolu, one of two main islands that make up the small Polynesian country of Samoa. The humidity, however, doesn’t dampen the anticipation lighting the faces of my family members, all awaiting steaming mugs of koko Sāmoa. In a big old teapot over an open fire, there are only three ingredients: a block of roasted Samoan cacao chopped into pieces, boiling water, and sugar to taste.

Drinking koko Sāmoa is a heady experience. The flavor is dark and intense, richer than an ordinary hot chocolate. But the best part is the crunchy cacao grinds, pegu koko, that cluster at the bottom of the cup. Chewing them releases the earthy, bitter flavor of natural cacao.

As each person receives an enamel cup filled to the brim, everyone settles into a familiar routine. There’s no schedule, no plan, but everyone knows that on this night, like many others before, stories will be retold, laughter will be incessant, and they will revel in the simple joys of spending time together over endless cups of koko.

According to Mataitai Malo, a Samoan security guard currently based in Australia, most family gatherings involve koko Sāmoa somehow. Nothing bolsters family unity more, he says, than “to just gather around to drink koko Sāmoa, have a laugh, and bring back memories from when they were growing up.”

Drinking koko Sāmoa is a national pastime, rivaling the local beer, Vailima, in popularity. Blocks of prepared and roasted koko, stored in plastic cups, are sold at markets, on the side of the road, and in small village stores.

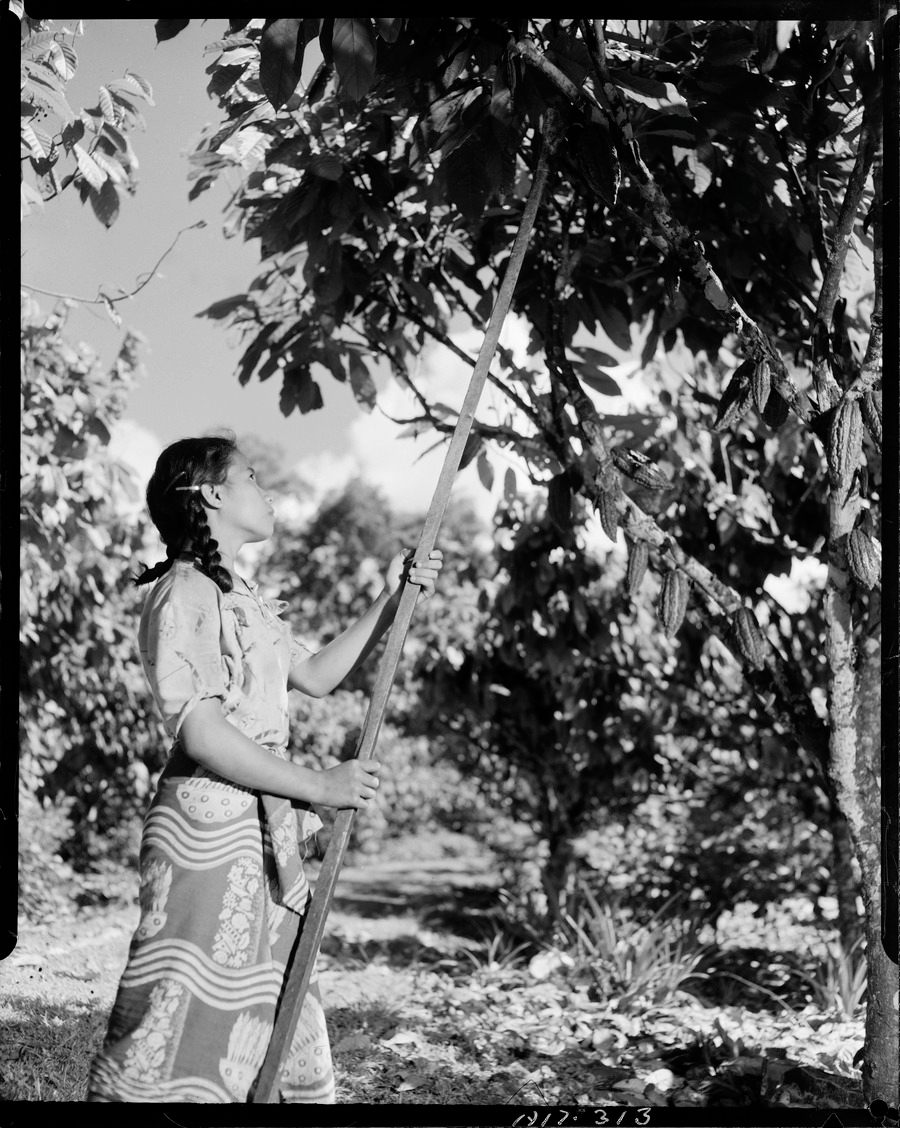

Yet many families in Samoa actually grow cacao and process it for their own consumption. The process of making it is long and labor-intense. First, the ripe pods are harvested, then the beans are roasted, shelled, and ground into a thick paste by hand. The paste is poured into plastic cups and eventually hardens into blocks, which can be chopped and mixed with hot water for use.

In a country where 97 percent of households grow their own crops for subsistence, cacao is an affordable, natural product, available to all. For Toia Vaatuitui, a bus driver in Samoa, the easy accessibility of koko is a source of pride. “We call it the koko Sāmoa, because it has become a national drink,” he explains. “Even when you’re in a poor family, or you think you’re poor because you just have taro, coconut cream, and koko Sāmoa for dinner, to me, that’s like being rich.”

Samoa also has a rich culture of oral traditions. Some of them even suggest that cacao was present in the islands long before European arrival, brought by Polynesian voyagers returning from distant South America. Garrett Hillyer, a scholar of Samoan food history, feels that he can only speculate on the subject. Some experts, he says, “have suggested that the sweet potato came to Oceania by way of South America, around the same time that cacao is sometimes said to have come from there.”

Officially, cacao arrived in Samoa in 1883, when Germans brought plants over from Ceylon to cultivate. As of yet, there’s no hard proof that Samoans acquired cacao before then. “Could there have been an extensive trading network between Oceania and South America during that time?” Hillyer ponders. “We certainly know that indigenous Oceanians have long been master navigators.”

While we may not know for certain at what point cacao was introduced to the islands, the German annexation of Samoa in 1900 brought with it the old, familiar colonial drive for profit and an increase in the commercial production of imported cacao, which grows extremely well in the region’s tropical climate.

However, the Germans found that they were unable to recruit enough Samoans willing to work the plantations. Hillyer notes that this was just one example of “active resistance by Samoans to colonial agendas.” A contemporary newspaper article exemplified the colonial attitudes widely held by white Europeans at the time: “It is well known that the Samoan … is a lazy man in his own country. There is no necessity for him to work, seeing that Nature supplies him with all that he requires.”

Due to the lack of local labor, the Germans hired workers from China and Melanesia to work in the cacao plantations. These plantations became a focal point for racism, oppression, and, eventually, resistance.

Despite discriminatory colonial laws against race-mixing, migrants who chose to stay in Samoa integrated into local society. After a long struggle against the Germans and, later, the New Zealand colonial administration, Western Samoa finally gained political independence in 1962. But the legacy of migration and the cacao plantations left the mark on the island, particularly on the food.

Many much-loved Samoan dishes today feature cacao and draw on ingredients brought to the islands by migrants. These range from koko alaisa, or cacao rice, to kopai, cacao dumplings, as well as koko esi, a cacao-papaya soup. Chocolate, then, is a daily staple in Samoan cooking. But only today is Samoan cacao starting to be recognised as a high-quality product, one that’s in-demand around the world.

Nia Belcher is the owner of Ola Pacifica, a New Zealand-based company which exports Samoan cacao to Switzerland to be made into artisan chocolate. She believes that the reason Samoan cacao has become a coveted flavor comes down to the individual farmers, and the island itself. Samoa “is very volcanic and it’s isolated. You have the tropical weather which is kind of rainforest-y, and the unique soil composition as well,” she says. “So I think that’s why it’s very different and it tastes different from other similar varieties around the world.”

But there’s one thing that truly sets Samoan cacao apart, she says. “The way people grow it, it’s not the same as in your big cacao-growing countries.” Cacao in Samoa today is cultivated mostly on small-scale family plots where growers cultivate cacao trees alongside other tropical crops as part of subsistence farming. In fact, Belcher started Ola Pacifica to help support these island communities. “It’s a great way that the growers can subsidize an income to help their families,” she says.

Despite the increasing interest and overseas demand for Samoan cacao, growing the bean remains a modest family affair in Samoa. Growing, grinding, and drinking a well-earned cup of koko Sāmoa while surrounded by loved ones is, and will continue to be, a cornerstone of daily life in this island nation. Mataitai Malo, the security guard, says it best. When asked what koko Sāmoa means to him, he replies simply. “It’s life. It’s paradise.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook