Kuppies, Cat-Dogs, And Other Pet Hybrids That Are Too Good to Be True

As if the world of nature itself weren’t captivating enough.

In December of 1970, a man named Roy Tutt told the world that he had accomplished what science deemed impossible: he had bred a dog and cat.

The nature-defying paramours were a black cat named Patch and Scottish terrier called Bones. After Tutt placed an ad in a local paper advertising their offspring—“Half cat-half dog. Offers invited.”—news spread, and reporters and photographers were dispatched to his home in an English village.

Tutt informed Reuters that the animals had dog’s heads and cat’s whiskers, fur, and legs. “I didn’t think much about it at first,” he said, improbably. “But now I feel slightly overwhelmed by the whole thing.”

Tutt’s story ricocheted across the Atlantic, where newspapers across the United States reported and republished versions of it. According to one account, he made television appearances and talked to international reporters, who flocked to his home. News organizations labeled them dog-cats, dats, cogs, kuppies, dittens, puppy-cat, and pussy pooch.

Tutt, who was 50 at the time, and whose profession was reported as both a pet shop owner and bookmaker, said he had been trying to mate the animals for ten years and that he fed them a mixture of cat and dog food.

“They are docile and good-tempered and should make good pets,” he was quoted as saying. “They will eat meat or fish and they make a noise between a yap and a meow.”

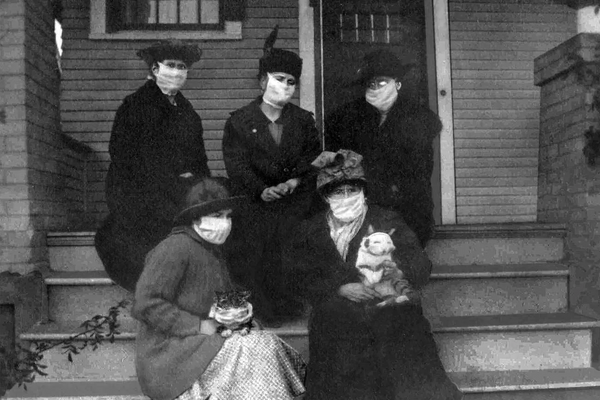

Pictures of the astounding animals accompany the stories: they are tiny, adorable, black and fluffy with floppy, triangular ears, and round trusting eyes

They are also obviously dogs.

Scams and hoaxes involving animals are all-too frequent and often dip into the fantastic, yet we buy into them, whether they’re stories of impossible births, impossible hybrids or tales of gullible would-be pet owners being duped into raising an un-cuddly or dangerous species. It’s as if the world of nature itself weren’t captivating enough.

Tutt wasn’t even the first to announce that particular brand of interspecies mingling. In 1937 the story of a Miami alley cat giving birth to dogs also captivated readers throughout the United States. Laura Bedford, who went by the nickname “Mom” and ran a barbecue stand, swore that her Maltese cat had produced three cats and two dogs. According to a United Press article, a veterinarian declared that “if” the incident was a hoax, that “somebody certainly went to a lot of trouble to match them up.” A day later, the same news service reported that three witnesses had come forward to discredit Bedford; Bedford stuck to her story.

A hybrid (very simply put) is an offspring produced from crossbreeding. And they do exist—mules, for instance, are the result of a horse and donkey mating. But creating hybrids of animals that are very genetically distinct from each other—such as a dog and a cat—is scientifically impossible, as is one species giving birth to an entirely different one. That has not stopped people from hoping.

In 1977, the story of a “cabbit” captivated the nation. A New Mexico rancher named Val Chapman claimed to be in the possession of a cat-rabbit mix that meowed like a cat, had hind legs like a rabbit, ate both cat food and carrots and excreted rabbit-like poop, according to a story in the Farmington Daily Times. Chapman named the creature Ricky Raccit and took it to California where the cabbit appeared on The Dinah Shore Show and Johnny Carson. In the midst of the media blitz, several experts tried to put the genetic impossibility in context. A curator at the Los Angeles Zoo told United Press International: “Let’s put it this way, can you mate a butterfly and a fish?” There have been stories of moose-horse matings (a “hoose”), pig-sheep hybrids, and jackalopes. During the 1700s, the world was even briefly enthralled by a woman who made the claim that she had given birth to rabbits.

Stories of scientifically impossible couplings and births are likely as old as the history of naming animals, according to Sarah Hartwell, an engineer with a keen interest in genetics, history and, cats. On her website, Messybeast, she has exhaustively chronicled a zoo of supposed hybrids, from the possible to the impossible, with an emphasis on fantastic cats. She has researched stories of cabbits, squittens, catacoons, guinea cats, and more.

“The Latin name for a giraffe is camelopardalis, hinting at a strange cross between two familiar creatures–a camel and a leopard,” Hartwell wrote in an email to Atlas Obscura.

The oldest documented case of impossible feline birth that Hartwell has encountered dates back to 1686 when a German physician, Gabriel Clauder, published an article stating that a cat had conceived a squirrel. (Hartwell surmises it is likely the cat simply adopted a baby squirrel.)

Before the study of genetics existed, it’s possible that such stories were the result of people trying to make sense of their world and the strange animals that sometimes passed through it. Modern perpetrators may be hoping for a bit of fame and money. And there are those who simply refuse to accept the facts, says Hartwell, who gets emails from “people who just don’t like rational explanations.

And indeed, the stories still surface. Cats giving birth to dogs in Brazil and China have been reported in recent years. Tales of mistaken identities are also popular. In 2013, a popular story claimed a would-be poodle owner bought a puppy from an Argentine market, only to find that the animal was a ferret doped up on steroids and fluffed to look like a poodle. The story sounds improbable and most likely is; the photograph that circulated with the story is of an actual animal called an Angora ferret. In 2018, a family in China reported that the pet it had believed for two years to be a Tibetan mastiff was actually an endangered Asiatic black bear.

Every April Fools Day, fabulous stories of nonexistent animals make the rounds: In 1984 the Orlando Sentinel chronicled the “mock walrus,” a tiny version of the enormous marine mammal. (The accompanying photo was of a naked mole rat.) In 2009 Catster trumpeted that Cornell University’s School of Veterinary Medicine had created a cat-dog hybrid.

Such stories depend heavily on audience buy-in.

“Humans want to believe—whether that is religion, alien abductions or impossible hybrids,” writes Hartwell. “In a mundane world they want to believe in wonders. In childhood we could believe in impossible creatures and maybe we lose that sense of wonder as we grow up. Reality can be rather boring.”

And, of course, such was the case with Roy Tutt’s dats.

It only took Tutt a few days to admit his hoax. The Associated Press reported that he collected a few pounds “for personal appearance interviews and photographs” before publishing a confession in The People, a Sunday newspaper. Tutt purchased the puppies (not kittens or dittens) for five shillings. Once publicity snowballed, Tutt felt like he had to “keep up the pretense.” according to United Press International.

It was not Tutt’s first time pulling a fast one. Once, he told Reuters, he had carried a stack of wet bills into a bar, claiming he found them washed up on the beach. The bar emptied as patrons went to seek their own fortune.

“I suppose I was born a practical joker,” said Tutt.

This story originally ran in 2015; it has been updated for 2022.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook