The Long, Complex History of Oakland’s Man-Made Bird Islands

This five-piece archipelago on California’s Lake Merritt is a unique avian hotspot.

Stand at just the right vista on the shore of Lake Merritt in Oakland, California, and you’ll see what appears to be a big island filled with dead trees, dense shrubs, and majestic birds—depending on the day, maybe double-crested cormorants, grebes, or black-crowned night herons. But walk a handful of paces and the mass will separate, revealing a five-piece archipelago where thousands of waterfowl make a home on their way across the lake or the world.

Although the archipelago is tantalizingly near both the shore and the lake’s boating area, the general public is not allowed within 50 yards, which gives the islands a mysterious appeal. The handful of parks workers and volunteers who have been lucky enough to walk its grounds describe the experience as a rare gift.

“It’s a visceral feeling—I could compare it to my first time traveling overseas, getting off the plane and realizing it’s the same sky, but you look around and everything is totally different,” says James Robinson, who grew up in Oakland and directs the nonprofit Lake Merritt Institute. “It’s a sensory overload, an experience of learning of how to be in the moment.”

The islands, the first of which was sculpted nearly 100 years ago from leftover construction dirt, reflect the political and ecological history of not just the lake, which is the nation’s oldest wildlife refuge, but also the city around it. They are a sanctuary within a sanctuary, hidden just out of view of the street, waiting to be discovered. “When you come inside the park, you see a ton of very cool-looking birds,” says Robinson. “You think, how is all this nature here in Oakland?”

Sitting nearly at the geographical center of the San Francisco Bay tidal estuary ecosystem, Lake Merritt is not actually a lake, but a lagoon, degraded for over two centuries by urban development. The Bay estuary, with its mix of salt and freshwater, is so perfectly-located and unusually biodiverse that it is considered both hemispherically and internationally significant by conservation groups; dozens of species of birds have, for centuries, stopped there to rest on long journeys down the Pacific Flyway, a migratory route that stretches from Alaska to Patagonia. And within this already unusual ecosystem, the lagoon is unique, its calmer inland environment and smoother waters providing a serene counterpart to rough coastal shores.

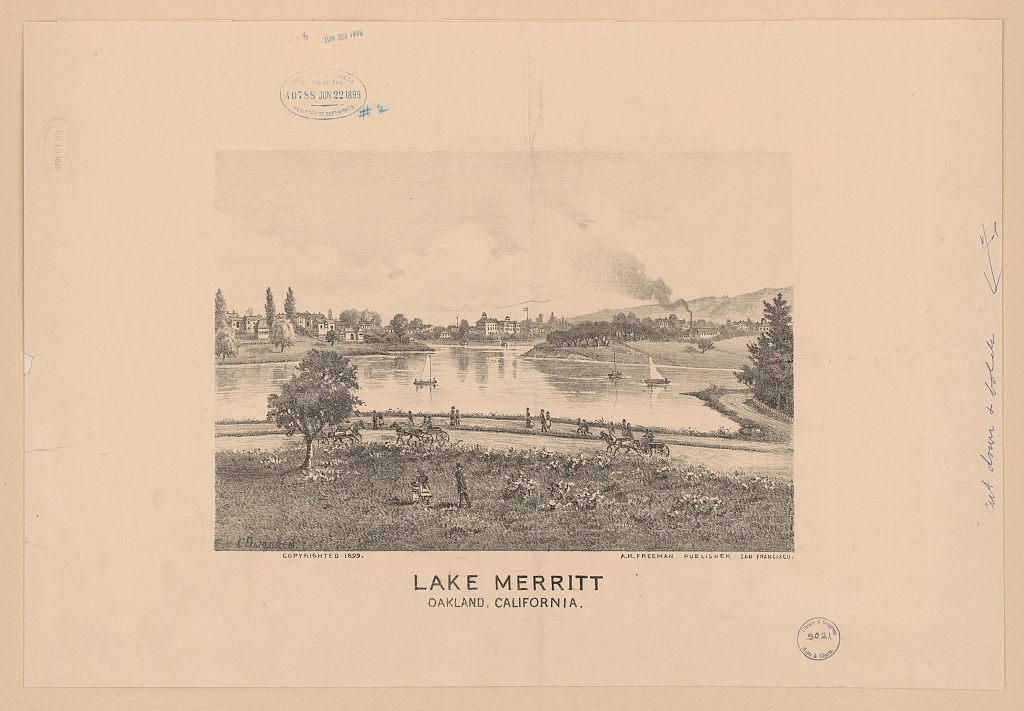

Throughout the early 1800s, as Oakland’s original city center grew a few miles away, on stolen Ohlone land, the lagoon became a sewage dump, an olfactory legacy that planners are still dealing with. The slow march toward cleanup began in 1869, when Samuel Merritt, a wealthy former doctor and Oakland’s 13th mayor, convinced the city council to install a dam, hoping regulated water levels would help hide the stench. A lake was born.

Unfortunately for Merritt’s substantial waterfront real estate investments, so was an ideal hunting ground. The lake exploded into an aviary wonderland of actual sitting ducks. Constant gunshot noise and the threat of stray bullets drove Merritt, on behalf of his wealthy neighbors, to barge his way through California’s bureaucracy and demand the lake become a nature preserve. In 1870, it was enshrined as North America’s first wildlife refuge, birthed more of capitalism than conservation.

Merritt died in 1890, but another mayor, John Davie, took up the birds’ cause upon his election in 1915. Nearly four decades as a refuge had made the lake a popular local attraction—more of a people sanctuary than a wildlife sanctuary—and Davie wanted to give the birds back some of their space. Construction of a 20,000-square-foot Duck Island finished on May 9, 1923; the mayor’s opponents, who considered dedicating an island to birds frivolous, called it Davie’s Folly.

Lake Merritt was already on its way to becoming the city’s “crown jewel,” and soon the island itself was a point of civic pride, with every improvement toward a resplendent sanctuary covered by the Oakland Tribune. Locals in 1924 celebrated the first batch of “native-son” ducks born on its shores, a brood that went on to star in a serialized radio play set on Duck Island that aired every Monday at 2 p.m. throughout the 1920s. “The Lake Merritt Ducks” was so popular that every episode got a full-column recap in the paper and, occasionally, fan art. Socialites even took inspiration from the island ducks for Mardi Gras costumes.

Meanwhile, the real birds were learning that the island and surrounding shores were safe places for stopovers free of land-based predators. Beginning in the 1930s, researchers from the U.S. Biological Survey banded ducks for tracking and study, an endorsement of the lake’s unique status: There were few other places that so reliably had so many birds so easily accessible.

“If you go to the lake today and you’re unaccustomed to it, you’ll be overwhelmed by how many birds there are, but in the 1940s and ’50s they were counting 4,000 a day that they didn’t get the day before,” says Hilary Powers, a birder who leads walking tours of the lake for the Golden Gate Audubon Society. “Tens of thousands over the course of the season.”

It was during this era in the mid-20th century that the birds got their most significant champion, although this time, he was motivated by conservation. In 1948, Paul Covel, a former zookeeper from Massachusetts, joined the Parks Department as the city naturalist.

“He was a self-taught ornithologist of the first degree, so in love with the variety of birds and so in love with the lake,” says Stephanie Benavidez, an Oakland native whom Covel hired to work at the refuge nearly five decades ago. “He saw his role as protecting the legacy of the sanctuary and carrying it into the future.”

All of Oakland’s natural environs were under Covel’s purview, but his avocation was the refuge. Between 1953 and 1954, he oversaw the construction of four more islands, this time from landscaping dirt, to join the original one. The first was also rejuvenated. Covel hoped to diversify the bird population, so plants—including Himalayan blackberry bushes, star acacias, eucalyptus trees, and bottlebrush—varied slightly island-to-island to allow birds to pick the arrangement that suited them best.

Wigeons, pintails, scaups, and goldeneyes began to nest alongside the mallards and canvasbacks. Some years, according to Benavidez, nearly 150 different species appeared over the course of a season. Covel and his staff revelled in explaining them all to visitors. “He knew the importance of making people feel responsible for helping to protect the beauty of what was going on around them,” says Benavidez.

But the variety did not last. Two decades later, as Covel prepared to retire, the bird population had declined to match an uptick in Oakland’s human population. Marshes nearby had turned to landfills for new housing stock, and a once-robust park staff dwindled to a handful. New birds continued to arrive, but their populations never matched the sheer volume of the mid-century flocks.

Benavidez took over as lead naturalist from her mentor in 1975, the same year that a raccoon infestation in the nearby Audubon Canyon Ranch nature preserve forced egrets there to relocate. They chose the islands, white egrets gracing tree branches and snowy ones burrowing into the bushes, pale feathers set off by the verdant green of the underbrush. They were soon joined by black-crowned night herons, and the islands “became a vivid rookery of bird life,” remembers Benavidez.

Meanwhile, the islands attracted birders by the thousands, from across the country and the world, who would stake out vantages for spotting a Barrow’s goldeneye or a bufflehead duck from much closer than they were accustomed to at home, or even in other sanctuaries. “The ease of seeing things here is unique,” says Powers. “The birds are just right there. They’ll give you the stink eye from [a few] feet away.”

The egret/heron regime destroyed much of the islands’ landscaping. It turned out the eucalyptus trees Covel had planted were no match for guano, or for the brackish mixture roots sucked up when rainwater muddled the lake’s natural saline content. By the early 2000s the trees had gone bare and died, leaving the herons and egrets without foliage for roosting. They moved out.

“It’s been a slow drama over the years,” says Powers, one that continued in 2003, when construction on the Bay and Carquinez Bridges evicted scores of double-crested cormorants from nooks underneath the roadways. Being seabirds that bask in direct heat, they started appearing on the islands’ tree branches, which were conveniently left shorn for maximum sun exposure by the previous occupants.

Since then, the permanent residents have predominantly been cormorants, although naturalists are trying to bring back the herons using decoys and recorded bird calls. Throughout all this, the islands themselves have proven robust, requiring only occasional maintenance and never additional dirt. In 2006, the city spent $1 million to shore up the edges, replace invasive plant species, install a new irrigation system, and add some living trees to attract foliage-loving bird species.

The biggest problem remains human beings. San Francisco’s decade-long housing crisis has continuously pushed new residents into Oakland, and those people every year push more and more trash into the lake, which can clog the irrigation system and hurt birds. Dissatisfied with being relegated to the shore, some visitors have begun flying drones across the islands to get closer to birds that are already unusually close. “People new to the city sometimes don’t seem to understand how to interact with the wildlife,” says Robinson.

While Oakland voters consistently prioritize the lake in funding measures, nothing can reverse the years of decline of surrounding habitats or increased stress of urbanization. Paul Covel warned of this on the occasion of the refuge’s centennial in 1970, reminding readers of Tribune that his work hadn’t truly “saved” the lake. “If we are to preserve Lake Merritt and the waterfowl refuge without gradual erosion of their natural values, we shall need your help,” he said.

Benavidez, who is now 65 and has been with the Parks Department for 48 years, takes after her mentor: She doesn’t think it’s too late. “The lake and the animals have adapted best they can to the sprawl and the Disneyfication, and this is what Paul was trying to get the staff to understand—it’s our job to get people to become responsible,” she says. “Once they’re responsible and fall in love, they will preserve and protect.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook