Lavinia Warren: Half of the 19th Century’s Tiniest, Richest Power Couple

Lavinia Warren. (Photo: Matthew Brady via Wikimedia Commons)

Lavinia Warren. (Photo: Matthew Brady via Wikimedia Commons)

When Lavinia Warren, a glamorous little person who was almost incomprehensibly famous in the 1860s, married fellow circus performer Tom Thumb, their lavish wedding at Manhattan was attended by nearly 10,000 guests, some paying up to $50 for the privilege. The circus impresario P.T. Barnum had successfully turned the couple’s 1863 nuptials into the social event of the season.

“No one need be surprised that two little matters should create such a tremendous hullabaloo, such a furore of excitement, such an intensity of interest,” wrote the New York Times in a breathless 5,200-word cover story about the union of “our Lilliputians.”

In the midst of the Civil War, President Lincoln even invited the pair to a White House reception during their honeymoon. Although they are little-known today, Lavinia Warren and Tom Thumb were the reality television stars of their day. “Next to Louis Napoleon,” wrote the Times, “there is no one person better known by reputation to high and low, rich and poor, than [Tom Thumb].”

It is hard to overstate the fascination that the public had with Thumb’s petite new bride, Lavinia. At one point later that year, P.T. Barnum offered her $5,000 to appear for six weeks in his museum, an amount equal to about $116,000 today. The 26-pound performer rejected his overture right away: ”As I do not intend giving a public exhibition until I have appeared before the Courts of Europe, and perhaps not even then, I must respectfully decline your offer.”

One of a pair of gloves designed for Lavinia, which she never wore since they were too big. (Photo: Sharon Bartholomew)

Options were slim for little people in the 19th century. Either they took low-paying work that kept them out of the public eye, or they subjected themselves to exploitation in sideshows. But Lavinia Warren, a fashion plate who ordered jewels from London and wore ermine capes to the theater, went from being a school teacher in Massachusetts to socializing with presidents and queens.

Lavinia Warren was born to a genteel New England family in 1841. She was a big baby, weighing in at nine pounds, and it wasn’t until she seemed to stop growing as a toddler that her parents suspected something was wrong. Lavinia was healthy and well-proportioned, but very, very tiny. After she was diagnosed with dwarfism, her parents didn’t treat her any differently; she was still expected to do chores. The only concession they made to her height was to build a stepstool for her so she could reach the kitchen table when cooking. Lavinia was encouraged to find a trade to support herself, and at sixteen she began to teach.

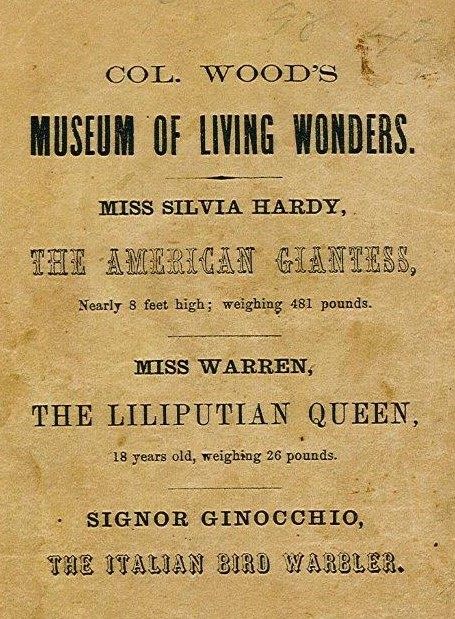

Program from Lavinia’s steamship career. (Courtesy: Kimberly Wadsworth)

Program from Lavinia’s steamship career. (Courtesy: Kimberly Wadsworth)

After a couple years, fame came calling. A cousin owned a showboat in Mississippi and persuaded Lavinia to spend one of her summer breaks on his boat, as part of a program he called “The Museum of Living Wonders.” Billed as “The Lilliputian Queen,” Lavinia would dance and sing show tunes and chat with the public. Sometimes she did a double act with Silvia Hardy–a giantess from Maine. They bunked together on the boat and became fast, if unlikely, friends. But the public was struck by Lavinia’s charisma and made her the real star. At the end of the summer, Lavinia asked to stay on.

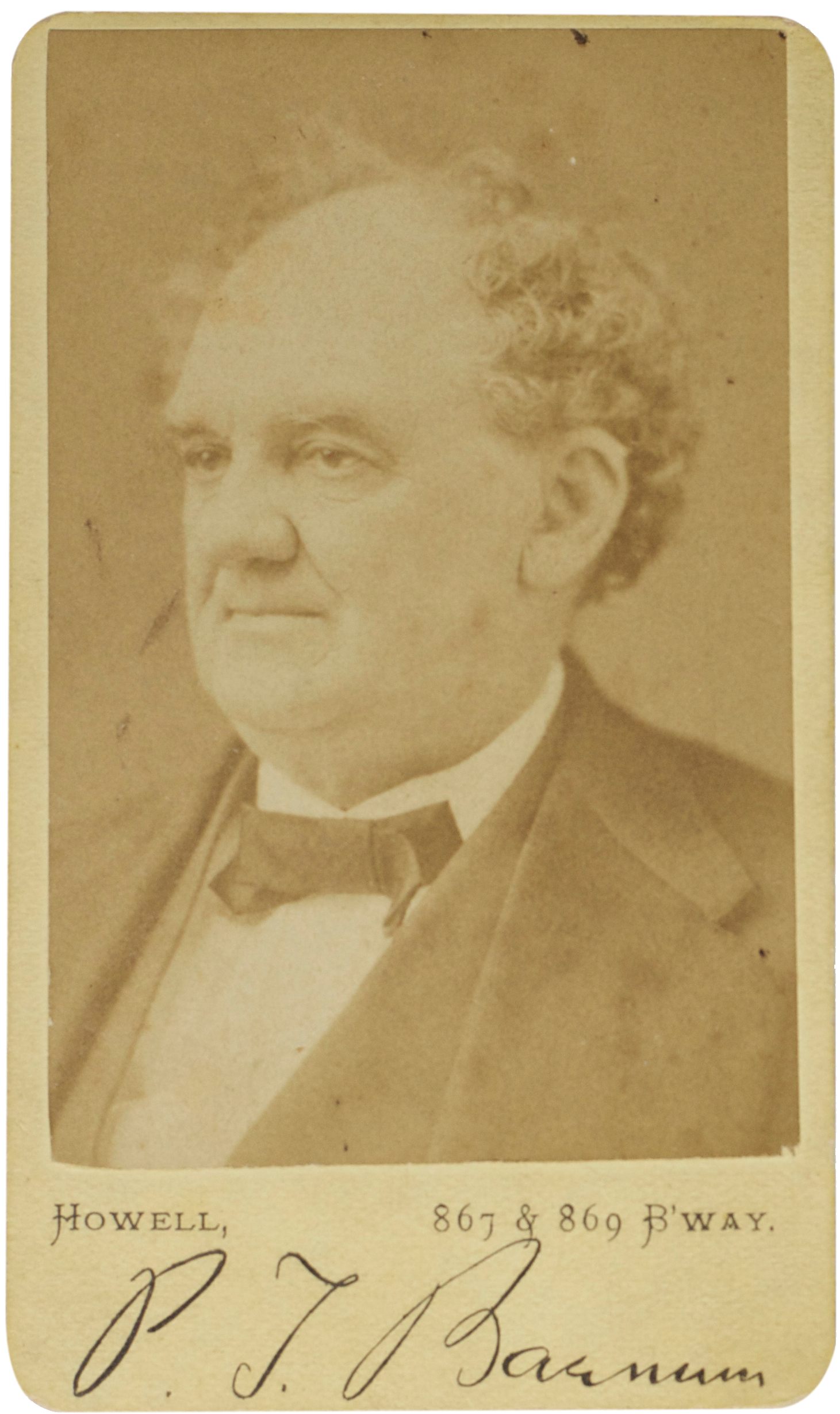

Within a few years, in 1862, the impresario P.T. Barnum came to meet her. Lavinia seemed an ideal addition to his museum–she could sing and dance, she spoke graciously and charmingly with her fans, and–she was single. And at the time, all the other little people Barnum employed were also eligible bachelors.

Portrait of P.T. Barnum. (Courtesy: Kimberly Wadsworth)

Portrait of P.T. Barnum. (Courtesy: Kimberly Wadsworth)

The first to meet Lavinia was “Commodore” George Nutt, another little person who fell for Lavinia at first sight. However, he was still a teenager, seven years her junior, and she wasn’t interested. But Charles Stratton was another story. Stratton, better known as “General Tom Thumb,” was one of Barnum’s most famous colleagues. The day Thumb met Lavinia, he took Barnum aside and asked him to help encourage their match, promising that Barnum could publicize their wedding if Lavinia became his. It was exactly what Barnum was hoping for, and he was all too happy to play matchmaker, giving Lavinia “fatherly advice” about Thumb’s wealth, fame, and good character.

Nutt didn’t take the snubbing well–he once once got into a fist fight with Thumb backstage, and on another night he decided to crash one of the couple’s dates. Unfortunately for Nutt, when he arrived, he learned that Thumb had just proposed–and Lavinia had said yes.

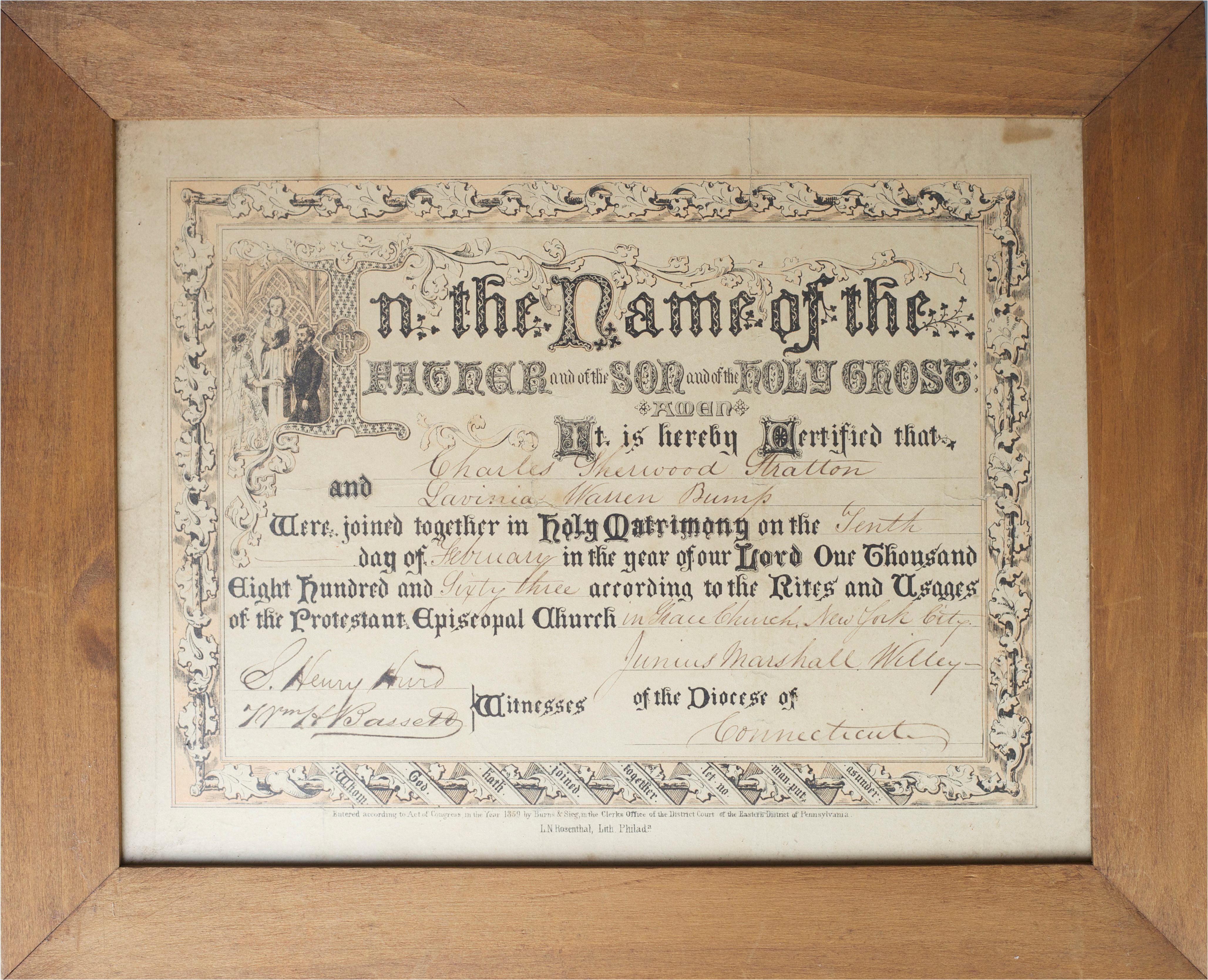

Charles Stratton & Lavinia Warren’s marriage license. (Photo: Sharon Bartholomew)

The wedding ceremony took place in New York’s Grace Church, a fashionable church on Broadway, and the reception was held at the equally stylish Metropolitan Hotel. Lavinia’s diminutive wedding dress was designed by Madame Demorest (the 19th-century Vera Wang) and was on display in her shop window for weeks before. Barnum even tried to set up Lavinia’s sister and maid of honor Minnie–also a little person–with Commodore Nutt, and even went so far as to pose them in a publicity shot depicting a “proposal” (alas, Minnie wasn’t interested in Nutt either).

Staged publicity photo of “Commodore” George Nutt and Minnie Warren. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Staged publicity photo of “Commodore” George Nutt and Minnie Warren. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

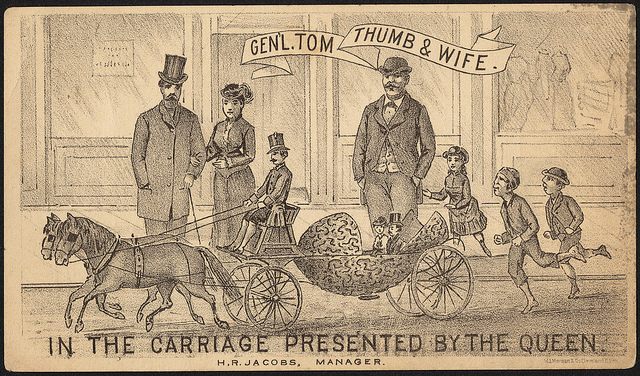

The thousands of people that attended the reception arrived to find the happy couple standing on top of a grand piano to receive them. Barnum also invited a few reporters; the Saturday Evening Post devoted a full column to the event, and the New York Times enumerated the wedding gifts in its aforementioned cover story: jewelry from Tiffany’s, a miniature billiards table, a carriage from Queen Victoria, and other delights. The Times also noted that during the service, Commodore Nutt looked a bit “ill,” but yet “the absurd reports concerning his jealousy and all that are grounded upon an exceedingly ill-bred habit of jesting at the expense of others, in which some people delight to indulge.”

Wedding photo with (left to right) Commodore Nutt, Tom Thumb, Rev. Wiley, Lavinia Warren, Minnie Warren. (Photo: Matthew Brady Studio, via Wikimedia Commons)

Wedding photo with (left to right) Commodore Nutt, Tom Thumb, Rev. Wiley, Lavinia Warren, Minnie Warren. (Photo: Matthew Brady Studio, via Wikimedia Commons)

The public ate up the story–not only out of fascination with the couple, but because it proved a welcome distraction from the ongoing Civil War. The New York Times story was actually the first time in three years the war hadn’t been on the front page. When President Lincoln received the couple at the White House during their honeymoon, he kissed Lavinia on the cheek, an act which she later told friends she thought was quite rude. Later Lincoln joked about the great difference between their heights and his own–“sometimes God likes to do funny things; and here you have the long and the short of it.”

1860s theater card depicting Charles and Lavinia in their carriage from Queen Victoria. (Image: Boston Public Library via Flickr)

1860s theater card depicting Charles and Lavinia in their carriage from Queen Victoria. (Image: Boston Public Library via Flickr)

A year after the wedding, Barnum quietly released press photos of Stratton and Lavinia–and a baby, nestled in Lavinia’s arms. Lavinia also cuddled a baby during her public appearances. The public once again went wild–so wild, in fact, that most didn’t notice that Lavinia never said the baby she held was hers. Instead, Barnum had borrowed the baby from a local orphanage.

For a while, Barnum kept using the same child during their appearances, but after a few months Lavinia pointed out that the baby was getting too big to be credibly passed off as theirs. She had a idea, though. She and Thumb were about to embark on a nationwide tour, along with Minnie and Commodore Nutt. Instead of dragging one child along with them everywhere, Lavinia suggested sending someone ahead to each town to secretly select a baby from the local orphanage, returning it after its day in the spotlight.

Not only would they make sure the babies were always small enough, she pointed out, but the tour wouldn’t have to worry about the expense of child care. Barnum agreed, and so a series of orphan babies all had their cameos with Lavinia during the tour.

Staged publicity photo with Stratton, Lavinia, and a baby borrowed from an orphanage. (Courtesy: Kimberly Wadsworth)

Lavinia and Tom never had their own children, as she always felt too uneasy about whether her size would cause complications during pregnancy or childbirth. Her sister Minnie did try to have children, and sadly, she proved Lavinia’s fears true. She carried her baby to term, but trying to deliver a six-pound baby proved too much for her. The baby died, and a few hours later Minnie did too, in her sister’s arms.

Lavinia and Minnie Warren, with Charles Stratton and their other brothers and sister. (Courtesy: Kimberly Wadsworth)

Tom and Lavinia lived comfortably and lavishly for the next 20 years, sometimes appearing at Barnum’s American Museum in New York or going on tours. But the high life of designer clothes and socializing with presidents had left Lavinia with expensive tastse. When Thumb died of a stroke in 1883, Lavinia found she did not have enough savings to retire. So in 1885, when she met another pair of performing little people from Italy–“Count” Primo Magri and his brother “Baron” Giuseppe–she married the Count, formed a tiny opera company and hit the road again, this time appearing with a roster of other performers.

Lavinia with her second husband, Count Primo Magri, and brother-in-law Giuseppe. (Photo: Swords Bros. via Wikimedia Commons)

Lavinia with her second husband, Count Primo Magri, and brother-in-law Giuseppe. (Photo: Swords Bros. via Wikimedia Commons)

They also made a silent film, The Lilliputians’ Courtship, in 1915. The public’s tastes had changed, though, and Lavinia was also not quite the attraction she’d once been. The couple found themselves gradually performing in seedier venues, including a guest appearance at Coney Island’s “Lilliputia Midget Village” in the early 1900s. Finally they gave up and returned to Lavinia’s hometown of Middleboro, Massachusetts, where they opened an ice cream shop, occasionally doing shows on the weekends.

Stratton Grave marker. (Photo: Staib via Wikimedia Commons)

Stratton Grave marker. (Photo: Staib via Wikimedia Commons)

Lavinia died in 1919, and in her will asked to be buried alongside her first husband, Charles Stratton, in Bridgeport, Connecticut. His gravestone is an obelisk bearing his name, topped with a life-size statue of himself; her marker is a simple headstone reading, “His Wife”.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook