Lemon Pigs Are the World’s Newest New Year’s Tradition

They go viral roughly every 50 years.

When Anna Pallai, author of 70s Dinner Party: The Good, the Bad and the Downright Ugly of Retro Food, posted the picture on Twitter, it was New Year’s Eve, 2017. A snapshot from a 1971 book on entertaining showed a goofy-looking pig statuette with an extremely confident caption: “For luck in the New Year, a Lemon Piglet is a must!”

Happy New Year (via granniepantries) pic.twitter.com/Am7zrKecEk

— 70s Dinner Party (@70s_party) December 31, 2017

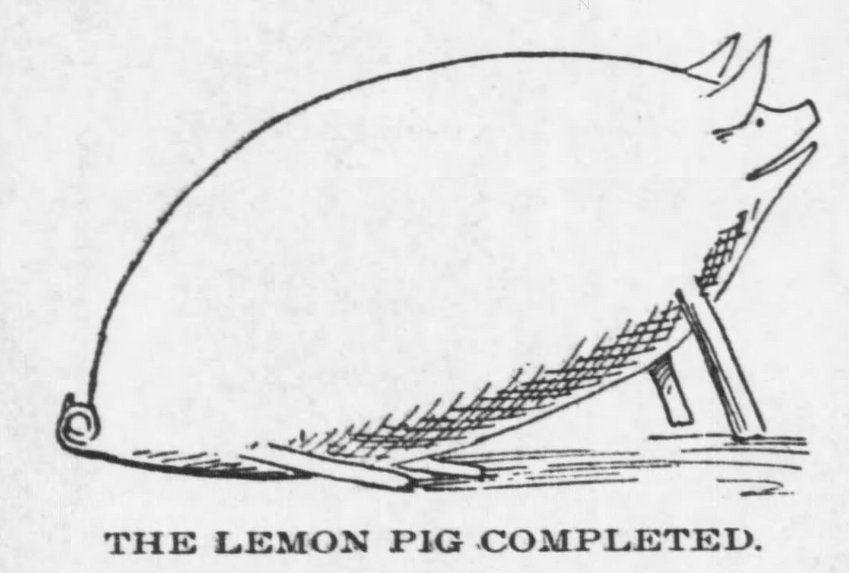

Pallai’s followers agreed, and soon she was deluged with dozens of lemon pig photos, cobbled together from fruit bowls and holiday detritus. The photo’s accompanying instructions are simple. Four toothpicks make up the pig’s legs, while small slices in the lemon peel create its mouth and ears. Two cloves are the eyes. The curly tail is fashioned from crushed up foil, and a glistening penny is inserted into the piggy’s mouth, presumably symbolizing the hoped-for luck. Even the lemonless joined in on the fun. Mandarin pigs and lime pigs joined the herd of citrus swine. An onion, as it turns out, makes a reasonable piglike shape, while a banana really does not. (“Sorry for the horror,” its creator wrote.)

But there is no actual tradition of making lemon pigs to ring in the new year. Instead, the lemon pig has a stranger backstory. And a certain appeal that seems to result in them trending about once every 50 years.

Pallai sourced the 1970s photo from Grannie Pantries, a vintage cookbook blog, which discovered the celebratory pig in 401 Party and Holiday Ideas from Alcoa. The blog describes it as “primarily a book dedicated to the proposition that parties would be far more festive if hosts would simply wrap every square inch of their homes in aluminum foil beforehand.” (Alcoa is an aluminum foil company, after all.) The curlicue, foil tail made the lemon pig includable.

But lemon pigs have been around for more than a century. An 1882 magazine story described a nearly identical lemon pig, and newspapers in the 1890s instructed readers how to make them. Instead of porcine good-luck charms, they were cheap craft projects for children, alongside “walnut witches” and cornhusk dolls. While they were most popular in the early 20th century, children’s entertainment books contained lemon pigs until the 1960s—just before their turn as aluminum-garnished party decor.

Pallai isn’t the only person who has helped the pigs gain visibility on the 50-year mark—the pigs have friends in high places. Famed chef Jacques Pépin likes lemon pigs so much that he describes how to make one in two recent cookbooks. Instead of foil for the tail, he recommends parsley. But in all my research, no other lemon pigs were lucky or had a New Year’s association. The authors of 401 Party and Holiday Ideas likely added that element themselves.

Pallai, who runs a literary agency in London, didn’t expect the lemon pig frenzy. She says people have made many of the retro recipes that she’s posted, such as salmon mousse and sauerkraut chocolate cake. The appeal of 1970s cuisine, she says, is that it seems fun and vivid, unlike the polished eats of Instagram.

But pigs got the biggest copycat response of all. “I never go out on New Year’s Eve,” says Pallai of their popularity, “and clearly a lot of other people would prefer to stay home and carve lemons than go to an overpriced bar.”

The comments accompanying people’s decked-out lemons reveal another reason for their popularity. “It can’t hurt,” was a common explanation from swine-makers. Along with the pig’s photogenic qualities, people longed for a bit of their luck.

Perhaps it’s to be expected, after the bruising experience of living through 2021, that it feels like we have to make our own luck. And if pigs don’t work, Pallai says she recently saw a tutorial on how to carve a zucchini shark. Watch out, 2022.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook