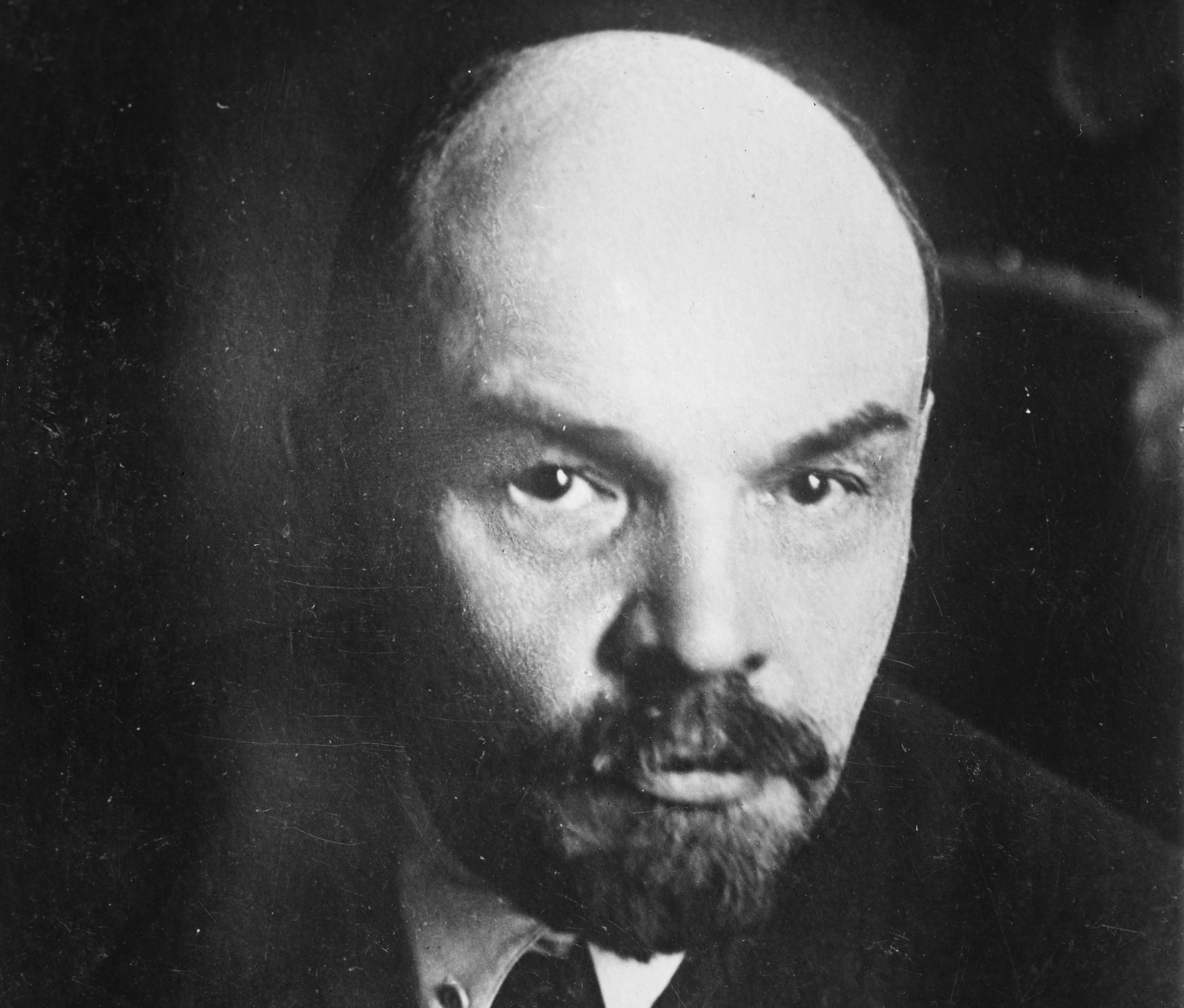

How Vladimir Lenin Became a Mushroom

The fake news that took the former Soviet Union by storm.

The world has its fair share of out-there conspiracy theories, but in the waning days of the Soviet Union, its citizens were introduced to one of the more ridiculous theories ever proposed: that, before he died, Vladimir I. Lenin had literally turned into a mushroom.

It was the middle of 1991, mere months before the collapse of the USSR, when this strange concept managed to gain a shockingly strong foothold in the popular consciousness of the Soviet people. The whole affair was a work of beautiful absurdity, and because it came at a time of incredible cultural change in Russia, it likely had a far larger impact than its orchestrators ever imagined.

“Until that year, it was 1991, it was very difficult to imagine that kind of hoax,” says Alexei Yurchak, an associate professor of socio-cultural and linguistic anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley. An accomplished Russian media scholar, Yurchak is the author of the essential essay on the event, A Parasite From Outer Space: How Sergei Kurekhin proved that Lenin was a mushroom. “The fact that he did it with Lenin made the hoax work. If he had used somebody else, it wouldn’t be feasible, but because it was Lenin, it was so hard to believe that this was a hoax.”

The Lenin-Mushroom hoax was the work of the musician-artist-performer Sergei Kuryokhin. The multi-hyphenate performance artist had been putting together provocative music and theater pieces since the 1970s, and was best known by the early 1990s for his group Pop-Mekhanika, a sort of noise orchestra that smashed together the sounds of rock ‘n’ roll, classical, live animals, and whatever else happened to be of passing interest. Kuryokhin created Pop-Mekhanika in the 1980s under the noses of the Soviet culture police, and gained a measure of fame among arty underground rabble-rousers. Whatever relative obscurity he still had came to an end on May 17, 1991, however, when he debuted his Lenin Was a Mushroom hoax on the Leningrad Television show Pyatoe Koleso (The Fifth Wheel).

Hosted by the film critic and journalist Sergei Sholokhov, The Fifth Wheel was an investigative television program not unlike 60 Minutes in the U.S. Born during the turbulent era of perestroika and glasnost, when relaxed regulations led to an opening up of Russian culture, the show was seen by its millions of viewers as a refreshing source of journalism and facts that had been kept from the public eye for so long. “A lot of media in perestroika was this sort of investigative journalism about the previous history. New facts surfaced, and there were new understandings of what had happened in Soviet history,” says Yurchak. “There was a lot of interest in the media, and a lot of people trusted the media, especially people who were not associated with the old media. The new young journalists.”

So when Sholokhov sat down with Kuryokhin in a book-crowded office for a segment called “Sensations and Hypotheses,” viewers assumed they were being presented with yet another piece in the cultural puzzle that was slowly, finally being revealed. “[Sholokhov] was extremely popular. He was one of these young journalists who became stars. They were trusted. They were not seen as someone who was creating superficial stories. They were known as serious, profound, investigatory types of guys,” says Yurchak.

Over the course of an hour, Kuryokhin, playing the part of the verbally precise scholar, built a loosely logical case that Lenin, after consuming a steady dose of psychedelic mushrooms over the course of several years, had at some point himself become a mushroom. Moreover, this transformation may have sparked the Bolshevik Revolution that brought him to power. According to the story presented, Kuryokhin had been traveling in Mexico when he came across some art associated with an early 20th century worker’s revolution that nearly mirrored images from the October Revolution of 1917. This, he continued, was proof of some kind of simultaneous parallel thinking, nearly an entire world apart, which he theorized could not be a coincidence. The common factor? Psychedelics.

Correlating the existence and use of hallucinogenic mushrooms in both Russia and Mexico, Kuryokhin posited that drugs had ultimately inspired the successful propaganda of the Russian revolution. In fact, Lenin had consumed so many mushrooms that their fungal “consciousness” had completely consumed him in return. By the end, Kuryokhin put it plainly, saying, “I have absolutely irrefutable proof that the October Revolution was carried out by people who had been consuming certain mushrooms for many years. And these mushrooms, in the process of being consumed by these people, had displaced their personalities. These people were turning into mushrooms. In other words, I simply want to say that Lenin was a mushroom.” He also made references to mushrooms being made out of radio waves, as if he didn’t already sound crackpot enough.

Included in the “proof” Kuryokhin offered to back up his hypothesis was some correspondence between Lenin and Stalin where the elder leader states that he felt good after eating some mushrooms; an unidentified, mushroom-like object found in pictures of Lenin in his study; and a ludicrous diagram comparing the famous armored car from which Lenin gave an influential speech to the root structure of a psychedelic mushroom. Kuryokhin presented an array of archival photos and old documentary footage, each one supposedly pointing to a clue that backed up his theory. But he moved on so quickly from each one that many viewers couldn’t tell that everything he was saying was utter nonsense. As Yurchak points out in his essay, Kuryokhin used real artifacts and photos to give credence to the ludicrous context he was attributing to them.

Sholokhov supported this act by sitting in stone-faced, rapt attention as Kuryokhin laid out his hoax. He even added a pre-recorded interview he did with an actual mycologist about psychedelic mushrooms, which did not mention anything about the Lenin angle.

Played completely straight, the bizarre program received a wide variety of reactions from a baffled public. In his essay, Yurchak, who interviewed a number of viewers in the early 1990s, writes, “While very few people claimed to have instantly recognized the program as a hoax, most remembered being perplexed, shaken, and uncertain about what to make of it.”

Some were initially inclined to believe the hoax outright, thanks to a mix of inherent trust of televised media and disbelief that anyone would fiddle with the legacy of a figure such as Lenin. Yurchak says that it wasn’t that the viewing audience was any more or less gullible than they are today, it’s just that people, everywhere in the world, have a tendency to believe what the TV says. “Often people don’t know there is evidence, but they assume there is evidence because otherwise they wouldn’t be talking about it. If there was something in the media, there must be something to it.” Others saw the show for the daring, provocative prank that it was, and had a good laugh. Many were just confused. “For weeks afterwards, millions of people were in limbo, like ‘what happened?’”

As shared in Yurchak’s essay, according to an account given by Sholokhov in a 2008 interview with the Russian women’s magazine Krestyanka, the day after the Kuryokhin episode aired, a group of Bolshevik veterans approached an official at the Leningrad Regional Party Committee and demanded to know whether it was true that Lenin had been a mushroom. Incredulous, she replied that the story had to be false, “Because a mammal cannot be a plant.”

Yurchak ultimately casts doubt about the veracity of Sholokhov’s story, but it speaks to the tenor of the hoax’s reception. The Lenin Was a Mushroom prank had forced viewers to stop and think about whether or not what they were hearing on television was true. Glasnost policies had renewed many people’s trust in their televisions, and Kuryokhin’s stunt forced millions to question not just the news, but the popular conception of Lenin as well. Plus, it made a lot of people laugh.

After the hoax aired, Kuryokhin earned national fame. In 1995, he began supporting the anti-liberal commentator Aleksandr Dugin, putting on a free concert in support of the man’s run for local office. According to Yurchak, who knew and spoke with Kuryokhin, this was another ironic provocation in response to a kind of starry-eyed neo-liberalism that was taking hold in the country, rather than evidence of Kuryokhin actually supporting Dugin’s ideas. In Yurchak’s essay, he writes, “[Kuryokhin] did not believe in absolute truth let alone in the idea of having unique access to it.” Kuryokhin died suddenly in July of 1996 of a rare cardiac sarcoma. At the time, some observers wondered if his untimely death was just another of his performances.

Decades later, Kuryokhin’s hoax is still remembered in Russian culture. While younger generations may not be immediately aware of the event, Yurchak says that the term “Lenin was a mushroom” is still used in common parlance, even if those using it aren’t aware of its origins. “When the discussions about the fate of Lenin’s body, or the fate of Lenin’s teachings resurface, which happens every year around the time of his birthday in April, they often joke about Lenin being a mushroom. They put it inside the different types of characterizations of Lenin, and it will be one of the jocular comments someone will crack.”

Kuryokhin’s hoax came out at just the right time, in just the right way, a feat that Yurchak says probably couldn’t happen again today. “We don’t have in Russia, or in the West, a situation where there are certain types of discourse or figures that are off limits for critical, ironic investigation. Where you can exploit that lack to create a hoax.” The debates about Lenin’s legacy continue to this day, but the debate over whether or not he is a mushroom is still far more entertaining.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook