The Improbable Endurance of the Lickable Envelope

Why are we still doing this?

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Over 120 years ago, in 1895, a businessman named Sigmund Fechheimer had the terrible luck of getting a paper cut on his tongue while licking an envelope.

What happened next, The New York World explained, was a tragedy:

S. Fechheimer died here yesterday from blood poisoning, as a result of cutting his tongue while licking an envelope.

Mr. Fechheimer’s death was a singular instance of the dangers of blood poisoning, and his case is almost unparalleled in medical history. Saturday night, in sealing an envelope, he pressed the mucilaged portion of it across his tongue. The edge of the envelope was sharp and cut his tongue so that it bled a little. The next day, his tongue began to swell and pain him. The symptoms of a serious case of blood poisoning were manifest to the doctor who was called to Mr. Fechheimer’s hotel Sunday.

The story was reported widely at the time—The New York Times even featured the situation in a small blurb—giving rise to all sorts of wacky misconceptions about lickable adhesives over the years, including whether envelope adhesive has gluten (it doesn’t), whether it’s made from animal byproducts (nope, it’s vegan—at least in the case of stamps), and whether it’s a way of distributing cockroach eggs (it isn’t, though such adhesives are actually a fairly nutrient-rich option for cockroaches, according to PETA).

Still, why, over a century later, are we still subjecting ourselves to this indignity? Consider that, when it comes to stamps, we’ve largely solved this problem, since most these days are self-adhesive, no licking required. The lickable envelope, on the other hand, lingers, a 19th-century innovation that was amazing before it was (briefly) deadly, before becoming what it is now: a cost-effective, pedestrian option notable only for the familiar taste and other corresponding connotations, like unpleasant trips to the post office. But in part thanks to the direct-mail industry, they just might be here to stay.

In the 1830s, when we first started using lickable adhesives on envelopes, they were, actually, a pretty big innovation.

That’s because while sending a letter isn’t a big deal these days, in the 19th century, it was, like many things then, horribly complicated, with postage in the United Kingdom, for example, that calculated postage fees by distance, instead of requiring a single stamp.

Fortunately, a man with an interest in both adhesives and simplifying the mail saw a way forward. His name was Rowland Hill, and in 1837, he released a booklet titled Post Office Reform: Its Importance and Practicability, which would prove hugely influential.

One of Hill’s big ideas? An adhesive stamp. From his booklet (highlights mine):

Persons unaccustomed to write letters, would, perhaps, be at a loss how to proceed. They might send or take their letters to the Post Office without having had recourse to the stamp. It is true that on presentation of the letter, the Receiver instead of accepting the money as postage, might take it as the price of a cover, or band, in which the bringer might immediately inclose the letter, and then redirect it. But the bringer would sometimes be unable to write. Perhaps this difficulty might be obviated by using a bit of paper just large enough to bear the stamp, and covered at the back with a glutinous wash, which the bringer might, by applying a little moisture, attach to the back of the letter, so as to avoid the necessity for re-directing it.

This idea, as we know today, would be one of Hill’s most lasting, making it possible for a letter-sender to pre-pay for postage.

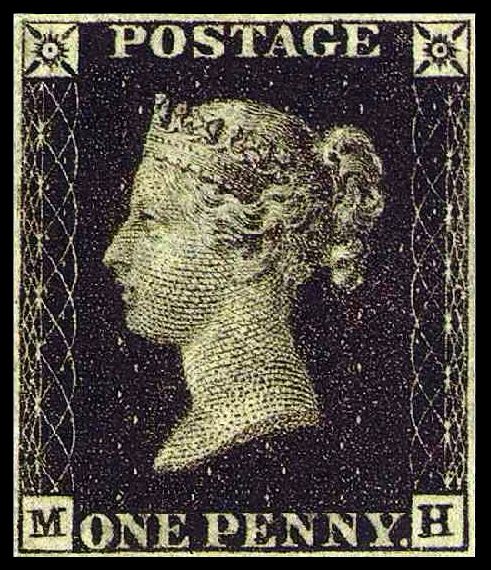

And, a few years later, Hill’s idea got its moment in primetime, with the debut of the Penny Black, a tiny illustration of Queen Victoria that was, like many stamps to come after it, lickable. During the first year alone, 68 million Penny Black stamps were applied to pieces of mail throughout the United Kingdom.

And while there are some other claimants to the title of earliest adhesive stamp, the Penny Black was a turning point for both stamps and the idea of licking paper to apply it to another piece of paper. The Penny Black ushered in the concept of “gumming” stamps, most commonly with substances like dextrin (a derivative of starch), and polyvinyl alcohol.

(If you do find yourself licking a stamp or a pile of envelopes, by the way, odds are that you might be consuming a couple of calories in the process. Per the Food and Drug Administration, gum arabic, a substance commonly used in stamps and envelopes, has around 1.7 calories per gram, which, by some estimates, equates around 0.1 calories per lick in the U.S. Not a ton, but it’s not the same everywhere. The U.K. Royal Mail, in one estimate to The Guardian, says that its stamps range from 5.9 calories to 14.5 calories. Don’t fill up on stamps.)

Considering all that, it seems weird that in an age where we have so many better options for adhesives that envelopes are still mostly stuck in the days when tongues do most of the work. Many stamps, for example, became self-adhesive long ago, first in Sierra Leone, where the humidity was so high that traditional stamps didn’t work so well, but also in the U.S., where it took a couple of tries before an attempt in 1989 finally stuck.

Back to lickable envelopes, though. Why are they still here? The biggest reason: the direct mail industry, which loves remoistenable adhesives, since they work really well for machines that ship out direct mail en masse.

Or, as the Envelope Manufacturers Association explains: “Remoistenable front seals reactivate with moisture and are the most common in use today due to their suitability for automatic inserting machines.”

These machines, perhaps unsurprisingly, are complicated, and, for direct mailers, a lot of variables go into creating perfect pieces of mail in bulk, like how much the seal curls, how well the seal handles humidity, and how the adhesive bonds to the paper.

And not all approaches are created equal. As the book Adhesives and Sealants: Technology, Applications and Markets explains, a process called hot-melt extrusion—which involves placing a hot adhesive directly onto the letter—has gained prominence within the industry because the end result is often more professional looking than simply moisturizing the adhesive on the envelope, as the goobers do it.

“Hot melts can be applied much more precisely than water-based systems and give a very polished and professional look with no curling of paper,” according to the book. “Conversely, water-based adhesives often look dull, have rough edges, and tend to curl the paper because moisture is added to only one side of the sheet.”

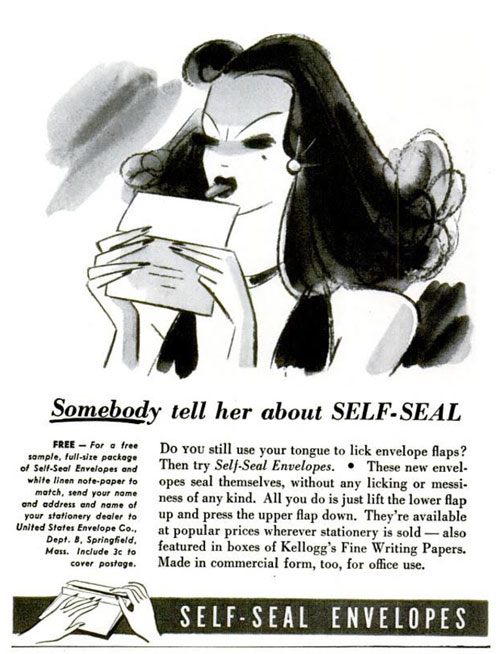

The consumer market, too, has long benefited from solutions that take some of the annoyance out of a truly tedious task. The Life Magazine ad above, for instance? It’s from 1941. But mass-mailers have completely different needs, which means we’re not going to get rid of licking envelopes anytime soon—even if there’s not a whole lot of actual licking going on.

And the truth might be that the reason why such envelopes persist in the consumer market is because they imply a personal touch, even if, in recent years, companies like Thankbot and Bond have come along to challenge our thinking about what constitutes hand-written. Lickable envelopes will probably, in other words, be around for the foreseeable future, or at least until the letter itself dies, at which point we’ll likely have fully submitted to our electronic destiny.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook