The Forgotten Sanatorium That Was Cooled by Cave Air

It was billed as the first air-conditioned building in the United States.

At the turn of the 20th century, a veteran heating and ventilation engineer named T.C. Northcott erected what amounted to the United States’s first air-conditioned building atop the summit of Cave Hill in Luray, Virginia. The building, known as the Limair Sanatorium, marked the culmination of Northcott’s 20-year obsession with cave air, which he believed could provide miraculous restorative benefits for those suffering from respiratory illness.

After completing the luxurious 5,000-square-foot plantation-style facility in late 1901, Northcott leapt at the opportunity to buy the property in 1905, and promptly established the Luray Caverns Corporation, which manages the caverns to this day. While it was the purchase and subsequent development of America’s third most visited show cave into a 400,000 visitor-per-year tourist attraction that secured Northcott’s legacy, his motivations for buying were very different.

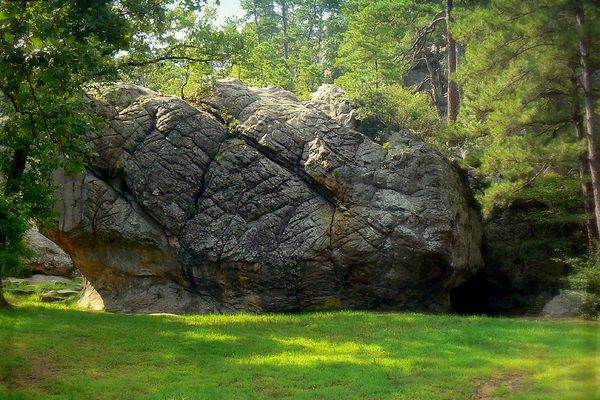

The Luray Caverns had been discovered and opened to the public for tours some 22 years before, but by the time Northcott leased them in early 1901, mismanagement had landed the owners in a heap of financial problems. According to resident historian and spokesperson Bill Huffman, these conditions likely contributed to Northcott’s ability to construct Limair, which entailed drilling into the caverns to access “lime air” that he believed had been disinfected by passing through miles of limestone chambers. “Otherwise, it probably wouldn’t have happened,” Huffman says.

“Mr. Northcott… has devoted many years to the problem of establishing an institution that would combine the advantages of sunlight and beautiful surroundings with an air supply at once voluminous and pure,” wrote Dr. Guy L. Hunner, a surgeon at the John Hopkins University Medical School. Hunner first visited Northcott’s Limair Sanatorium while vacationing in the Shenandoah Valley in 1901. “After investigating the caves of New York, Ohio, and Virginia, he secured building and park privileges over the Luray Caverns as a site comprising the greatest number of healthful and attractive features.”

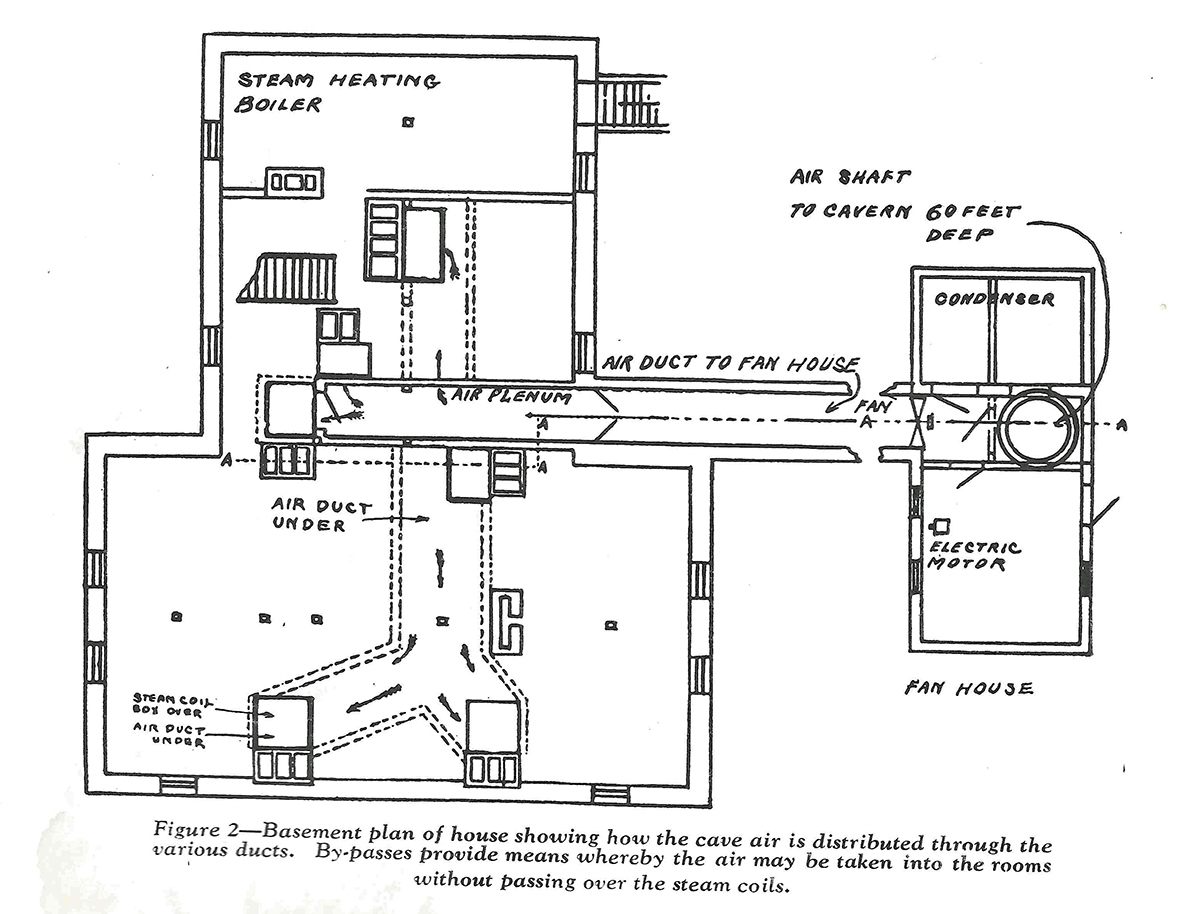

In addition to its location directly above the caverns, the site looked out on the neighboring valley and was surrounded by panoramic views of the Blue Ridge Mountains—the Massanutten Range to the west and, to the east, what is now Shenandoah National Park. Northcott drilled straight down through the hill and 60 feet of rock into the ceiling of a prominent chamber now known as Morrison’s Hall. Installing a five-foot in diameter ventilation shaft, he effectively connected the sanatorium’s basement to the caves. Equipped with a fan powered by a five-horsepower steam engine, the system enabled Northcott to pump cavern air into the facility 24 hours a day.

“Not only that, he engineered the building so that the system would completely replace every molecule of air in the building every five minutes on the dot,” says Luray Caverns facilities engineer Chad Painter.

Thus, convalescents could breathe a continuous supply of “lime air” while enjoying abundant sunlight and prodigious views. “The idea was for people to live here almost as if they weren’t sick,” says Huffman. There were windows everywhere. There were activities and even dances. There was excellent food. Northcott’s view was that, if a patient was going to get better, that person shouldn’t feel quarantined away from the world so much as a part of it.

Northcott went to great lengths to keep the temperature at a perpetually even 70 degrees. During the summers, that meant air-conditioning, although not in the way we conceive of the process today. “The air drawn from the caverns being about 54 degrees, when forced into the building, cools the rooms to any degree comfort may demand, however intense the heat prevailing outside,” observed Hunner. In winter, the comparatively balmy air was given a boost by passing through a series of chambers featuring coils filled with steam. Humidity was regulated by a series of condensers year-round.

Northcott’s faith in cave air derived from a belief that, like water passing into an aquifer, it had been cleansed by a process of natural filtration. “He claimed the air was purified as it was drawn into the caverns through the rocks and porous soil, sanitized by the limestone, and ‘finished’ as it floated over underground springs and pools,” explains Huffman. “He talked about the air as if it were a mix between holy water and fine wine.”

While it may sound strange now, in his time, Northcott’s enthusiasm was convincing enough to inspire respected medical professionals like Hunner to pursue scientific validation. Returning to Limair in 1902, a polite but skeptical Hunner came prepared to conduct a series of experiments. “At my first visit… I saw demonstrated the remarkable volume in which the air enters and leaves each room without creating appreciable draughts, and the fact that the air is practically free from atmospheric dust,” he wrote, dwelling at great length about how invaluable the latter was for respiratory convalescents. “Noting this fact, I became interested in the bacteriologic condition, and determined to visit Luray again, supplied with culture media and sterile plates.”

That December, the doctor spent four days studying the air in the caverns, sanatorium, surrounding landscape, and neighboring homes. His findings were remarkable. He conducted numerous tests for bacteriological cultures. He tested each room in the sanatorium, and the most contaminated plate yielded a mere nine colonies total (and the readings were admittedly taken following a party Hunner described as a “particularly large ball”). The home of a nearby farmer showed 143 colonies, and a local physician’s office showed 92. By means of comparison, Hunner tested the air in the John Hopkins gynecologic operating room and found 65 colonies. The ambient air outside his home in Washington D.C., meanwhile, tested at over 450.

“But in spite of the bacteriologic purity of the air in Limair Sanitarium, I am sure many will protest against breathing the polluted, moldy emanations from a source never penetrated by the rays of the sun… I must confess this was my first impression, and the same prejudice has been expressed by many friends with whom I have conversed,” wrote Hunner. Arguing the experimental evidence, disinfecting qualities of lime, and pointing to the fact that “we find no organic matter in the caverns undergoing decomposition,” Hunner subsequently confessed himself a convert.

“For hay fever, asthma and all bronchial affections, the conditions [at Limair] are ideal,” he concluded.

In the end, despite his enthusiastic testimony published in a 1904 edition of Popular Science Monthly, Hunner’s colleagues were loath to acknowledge his findings. For good or ill, the opinion never gained traction among the medical community, and was dismissed as a curious historical footnote. Limair continued operating quietly in the Virginia hills until it burned down in April of 1940. While the building was replaced, it did not operate as a sanatorium. Instead, Limair was reinvisioned as an elegant southern-style meeting and reception hall in brick, albeit one with an unconventional—and still functional—cooling system.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook