The 19th-Century Lithuanians Who Smuggled Books to Save Their Language

They banded together against book burnings to fight an empire.

In 1899, a pair of smugglers were crossing the border between Lithuania and East Prussia. Clutching their packs, they lay on a bank along the Prussian part of the river Šešupe, and for hours they studied the movements of the guards on the other side. They could not afford to get caught.

When it was dark, they pushed across the Šešupe and ran 10 miles to a distribution center in the Lithuanian village of Pilviškiai. There they discovered that Russian authorities were searching for them.

Soon they would return to Prussia, where they would hide out for several weeks before deciding to abandon the region entirely. Within a year, they would be on a boat to Scotland.

But that first night, before they fled, they needed to drop off their smuggled goods—the very reason that authorities were after them. They opened their packs, and out poured books.

In 2004, a Lithuanian man named Jonas Stepšis recounted this story. The two smugglers were his father and uncle, and they had joined what became a nationwide book-smuggling movement as a part of their opposition to the Russian Empire.

Tsarist Russia had dominated Lithuania after Poland-Lithuania, a Commonwealth formed in 1569, was annexed and divided up among Prussia, Austria, and Russia in 1795. The majority of Lithuania fell under Russian control.

Tsars tried early on to enforce loyalty, finding a particular target in the Roman Catholic Church—an historic Lithuanian institution that Russia saw as a threat to its power. Russian authorities demolished numerous chapels and prohibited the construction of wayside shrines, which were essentially omnipresent throughout Lithuania (there were roughly two shrines per kilometer). Not prepared to give up their culture, Lithuanians built new shrines anyway.

Though a group of Lithuanian university students and clergy led a violent uprising against Russia in 1831, resistance had long operated on a small scale. Lithuania had a tiny population (around one million people) and stood little chance of defeating a military power like the Russian Empire.

But by the middle of the 19th century, that was changing. The resistance had intensified.

In 1863, a massive insurrection: some 66,000 Lithuanians serfs, traders, and clergy took up arms against the Russian government. Soon after their rebellion was crushed, leaving thousands dead or exiled to Siberia, Tsar Alexander II issued a harsh crackdown.

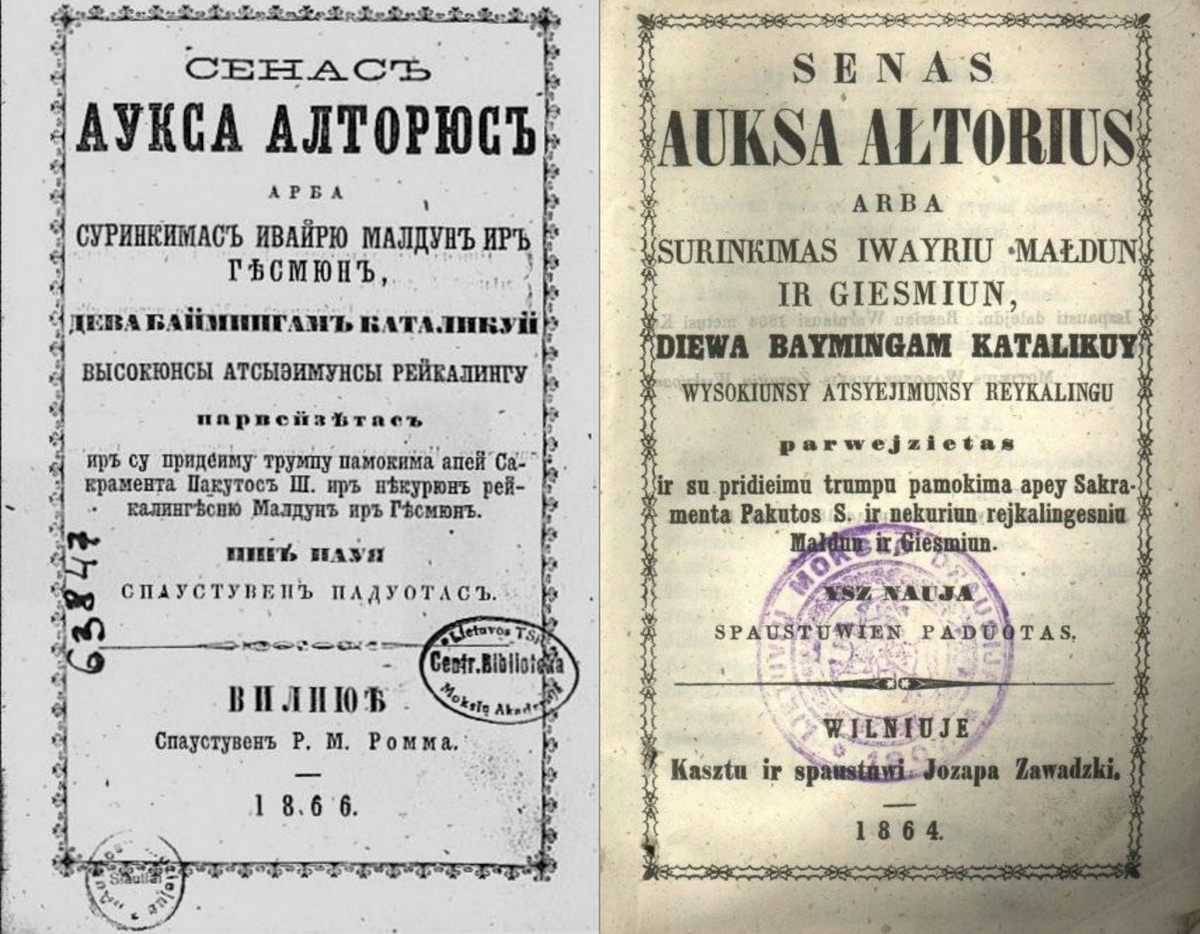

In 1864, the Governor General of Lithuania, Mikhail Muravyov, forbade the use of Latin Lithuanian language primers—a proclamation that, two years later, led to a total ban on the Lithuanian press.

Language had long been a point of contention in Tsarist Lithuania. In the middle of the 19th century, in order to assimilate the peasant class, the Russian scholar Alexander Hilferding proposed that the Lithuanian language, which uses a Latin alphabet, be converted to a Russian Cyrillic alphabet.

The Lithuanian press ban was therefore an attempt to eradicate the Lithuanian language and promote loyalty to the Russian cause. Lithuanian children were also required to attend Russian state schools, where they would learn the Cyrillic alphabet through books printed by the Russian government.

According to historians, Russia thought little of the ban when they first initiated it. They didn’t see Lithuanians as belonging to a unique nationality, and they assumed that resistance, if anything, would be minimal.

They were wrong.

Almost immediately, individuals sprung up to spread Lithuanian writing. Since they couldn’t publish books in their homeland, many Lithuanians began printing them abroad and smuggling them back into their own country.

Thus appeared the first of the knygnešiai—or book-carriers—who, in a desperate bid to save their language, transported books across the border and illegally disseminated them throughout Lithuania.

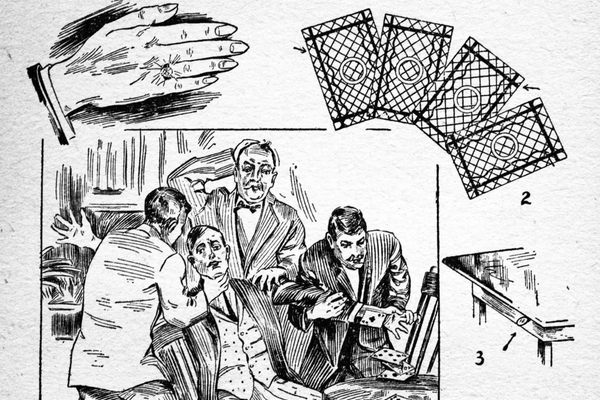

Initially, the knygnešiai worked alone. They carried books in sacks or covered wagons, delivering them to stations set up throughout Lithuania. They performed most of their operations at night, when the fewest guards were stationed along the border. Winter months—especially during blizzards—were popular crossing times.

Lithuanians went to great lengths to conceal their illegal books. The Forty Years of Darkness by Juozas Vaišnora reports of female smugglers who dressed as beggars and hid books in sacks of cheese, eggs, or bread. Some even strapped tool belts to their waists and pretended to be craftsmen, disguising newspapers under their thick clothes.

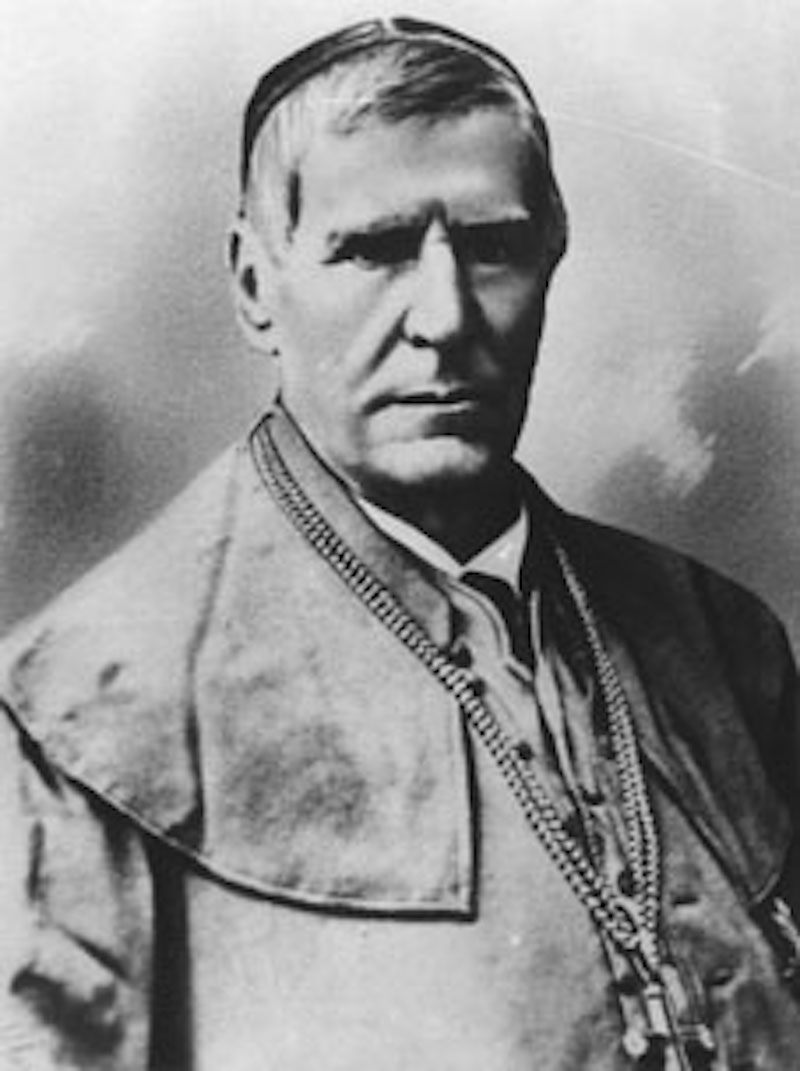

Bishop Motiejus Valančius, a historian and author of religious and secular works who later earned the label “the greatest Lithuanian personality in the 19th century,” organized the first large-scale attempt to smuggle books across the Lithuanian border. In a bid to publish more prayer books, he sent money to neighboring Prussia to construct a printing press there. Beginning in 1867, he tasked a number of priests with bringing the books back into Lithuania and distributing them to locals.

Though at first Valančius only published Latin reprints of religious texts, as his operation grew, so did his ambitions. He began to commission original works, including many he had written, and his burgeoning team shuttled them across the border.

The fact that so many of these early smugglers were priests is not surprising. Lithuania’s strong Catholic roots—and Tsarist Russia’s historic hostility to the Church—made the Catholic Church an instant symbol of resistance to Russian authority. But as the smuggling operations continued, they became more secular in character. In addition to prayer books, Valančius started printing journals and almanacs in Latin Lithuanian with the hopes of teaching Lithuanian history and culture. He was responsible for the printing of over 19,000 books in East Prussia.

Following the lead of Valančius, individual knygnešiai soon organized themselves into larger smuggling societies that bore optimistic names like the Morning Star, Stimulus, Rebirth, the Sprout, the Truth, Compulsion, and the Ray of Light. They began importing books from as far away as the United States, where the sizable Lithuanian-American populated assisted them in printing. (Over 700 copies of Lithuanian books were published there.) These new organizations distributed textbooks, yearbooks, science books, fiction, folklore, religious sermons, and other publications.

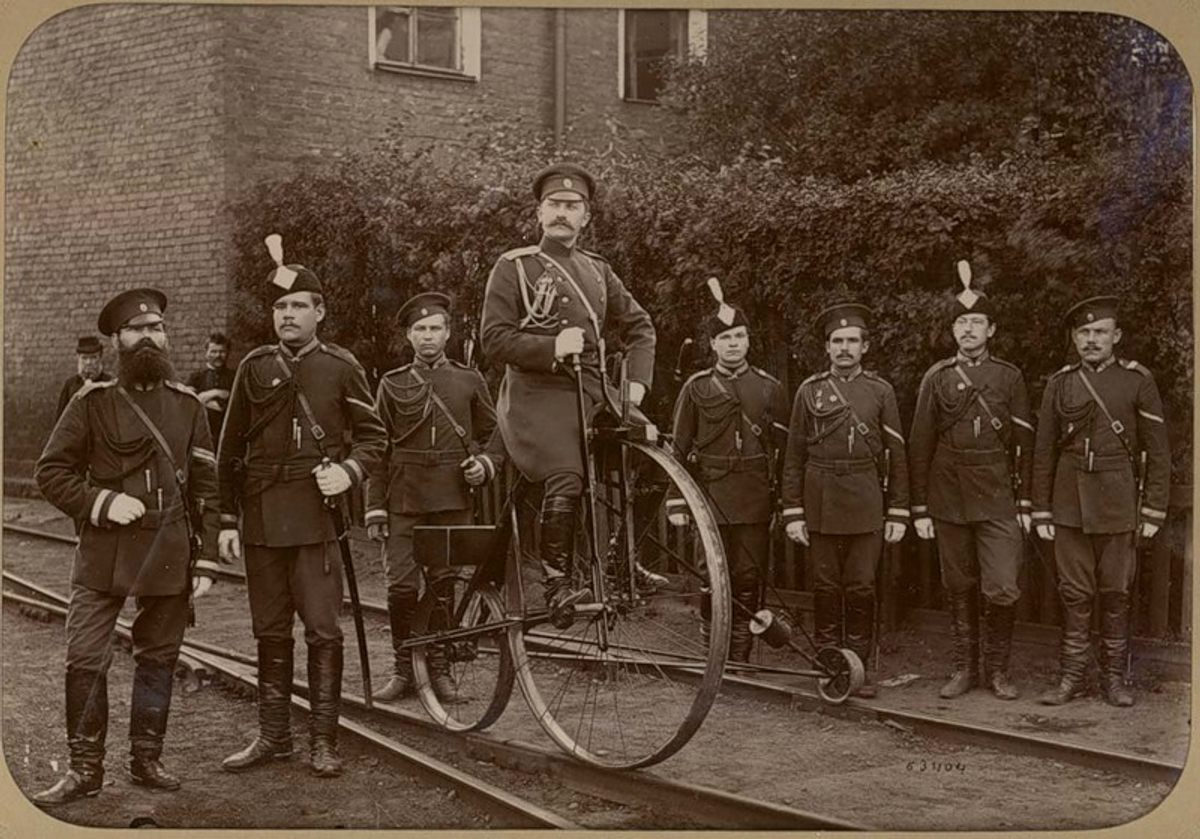

Despite its popularity, smuggling was far from easy. The risks were high, and the Lithuanian border was not easy to cross. Three lines of Russian security forced the knygnešiai to exercise extreme caution.

The first line comprised soldiers along the border “filed so densely that they could see each other.” In the second line, another row of soldiers waited, this time spread further out. The last defenses were the gendarmes—or Russian Empire policemen—who rode on horseback through villages and sought information from local informants.

Those who failed to beat the Russian border security were “tied to a post and whipped,” then either imprisoned, sent to Siberia, or—if they tried to run—simply shot.

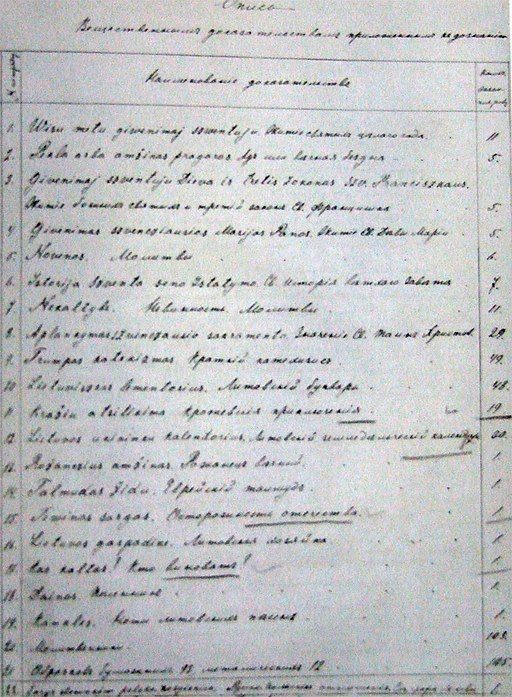

Soldiers confiscated any books and journals found on the smugglers—and burned them.

The number of book smugglers that were caught or punished is unclear, but the first major arrest seems to have occurred between 1870 and 1871, when Russian forces sentenced 11 associates of Valančius. Eight of the smugglers—five priests, a farmer, and a noble—were exiled to Siberia. Valančius’ operation was permanently compromised. A few years later, in 1875, he died.

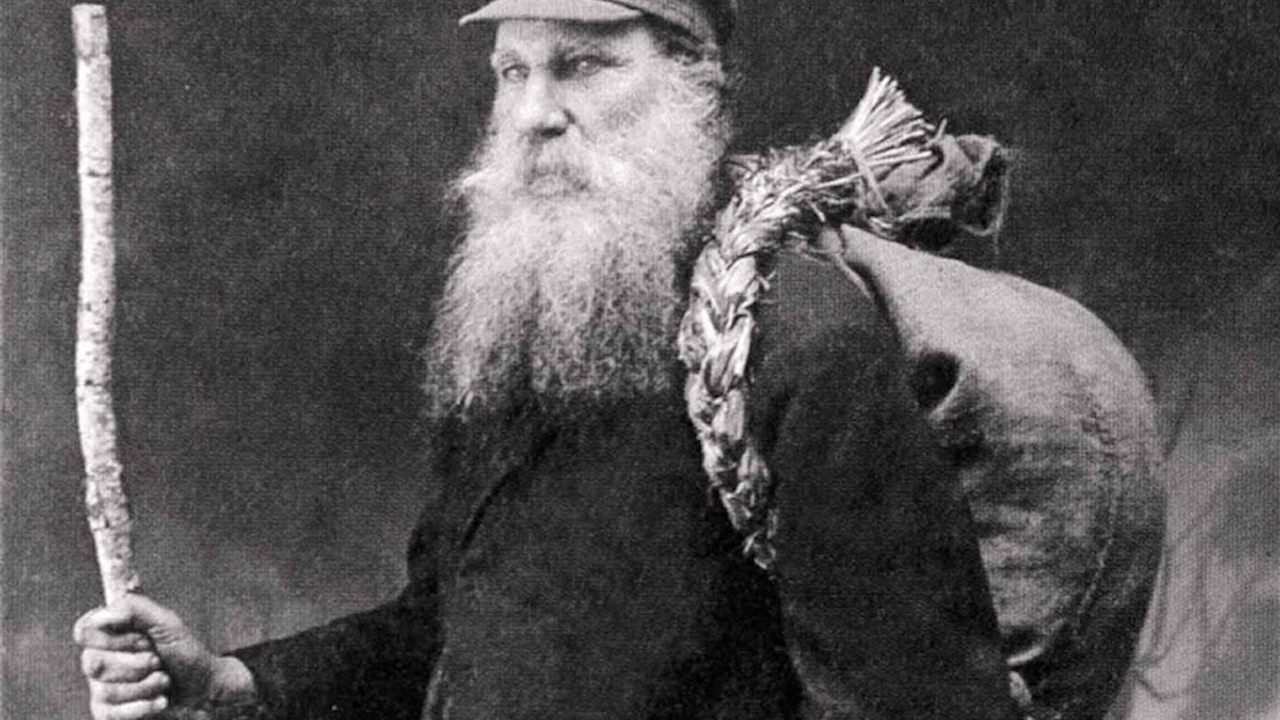

His de facto successor was a peasant: Jurgis Bielinis, an ardent Lithuanian nationalist who inherited his political edge from his father.

Bielinis met Valančius in 1873, a year after he graduated from a university in Rīga, Latvia. By then, the resistance was in full swing, and as a passionate defender of Lithuania, Bielinis wanted in. His contact with Valančius determined him to defend the language he loved. He would not rest, he said, until “the Muscovites got out of Lithuania.”

In 1885, Bielinis created the Garšviai knygnešiai society, which grew to be the largest book-carrying operation in Lithuania, later earning him the title of “King of the Book Carriers.” Members of the Garšviai knygnešiai society—who soon numbered in the thousands—pooled together money to buy books from Prussian publishers and then distributed them to paying “subscribers” throughout Lithuania. Bielinis is credited with smuggling nearly half of all of the books brought into Lithuania from East Prussia (and even passing some along to Lithuanians living in Latvia).

By the 1890s, Russian authorities were on his case, and a reward was placed on him. Several manhunts ensued, but Bielinis consistently managed to evade capture.

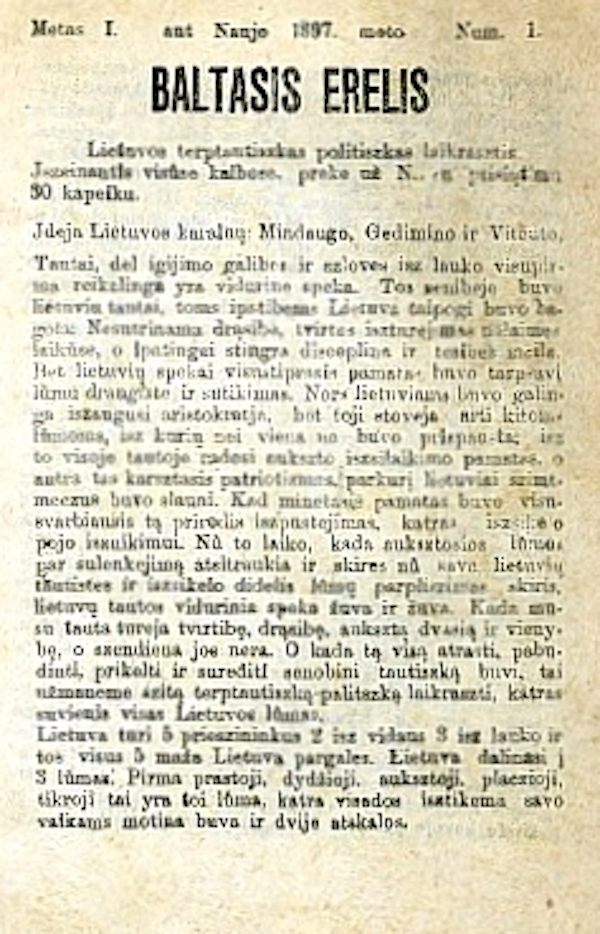

At the turn of the century, despite his fugitive status, Bielinis even created a Lithuanian newspaper of his own, which he delivered to residents who bought a subscription from him. The newspaper, known as the White Eagle, was printed on one of the only presses active in Lithuania.

He worked on the project with fellow smuggler Steponas Povilionis, who recalled:

“In my house, there used to be a book warehouse of Bielinis, which continuously increase or decrease in volumes. In autumn 1896, Bielinis brought from Prussia a small printing press and decided he wanted to publish a newspaper of his own. I made a draw for letters, and Bielinis taught me to assemble them”

Yet Bielinis’ trajectory from peasant to intellectual and defender of the Lithuanian language was not uncommon: since the Russian Empire abolished serfdom in 1861, a new class of peasant-intellectuals had begun to take shape in Lithuania. Many became active in the national cause.

In fact, peasants, which Zigmantas Kiaupa in The History of Lithuania describes as “the most faithful user[s] of the Lithuanian language,” comprised the vast majority of the knygnešiai. According to the same book, roughly 86 percent of smugglers were peasants. Bielinis was only the most visible member of a rising national peasant movement.

By the late 1800s, the knygnešiai were getting creative. Some managed to enlist the help of Russian police—for example, in 1895, the head officer of Ariogala in central Lithuania joined the smuggling conspiracy. Others exploited loopholes in the press ban. In one instance, Lithuanians printed texts on slabs of clay as the Babylonians had once done. To the chagrin of authorities, clay tablets weren’t considered books, so they technically weren’t illegal.

Locals also set up secret schools that taught Lithuanian children their language using illegal books. To avoid attention, Lithuanian children still attended Russian-operated state schools, but it was in the Lithuanian schools, they were told, where their real education happened.

It is unclear how many Lithuanian books were printed and smuggled illegally, but between 1891 and 1901, Russian officials confiscated over 173,259 publications, a rate that nearly doubled in the remaining few years of the ban (1901-1904). This has led some historians to estimate that the actual numbers of smuggled books totaled in the millions. Regardless, nearly every town and village had a stockpile of illegal books and a secret Lithuanian school to go with it.

By the height of the book smuggling operations at the end of the 19th century, all sorts of Lithuanians participated: once the illegal publications were ferried across the border, everyone from traveling salesmen to poor widows, farmers, students, doctors, and organists conspired to distribute them. Mere possession of illegal books could incur harsh punishments, but this did not faze Lithuanians who felt they had little left to lose.

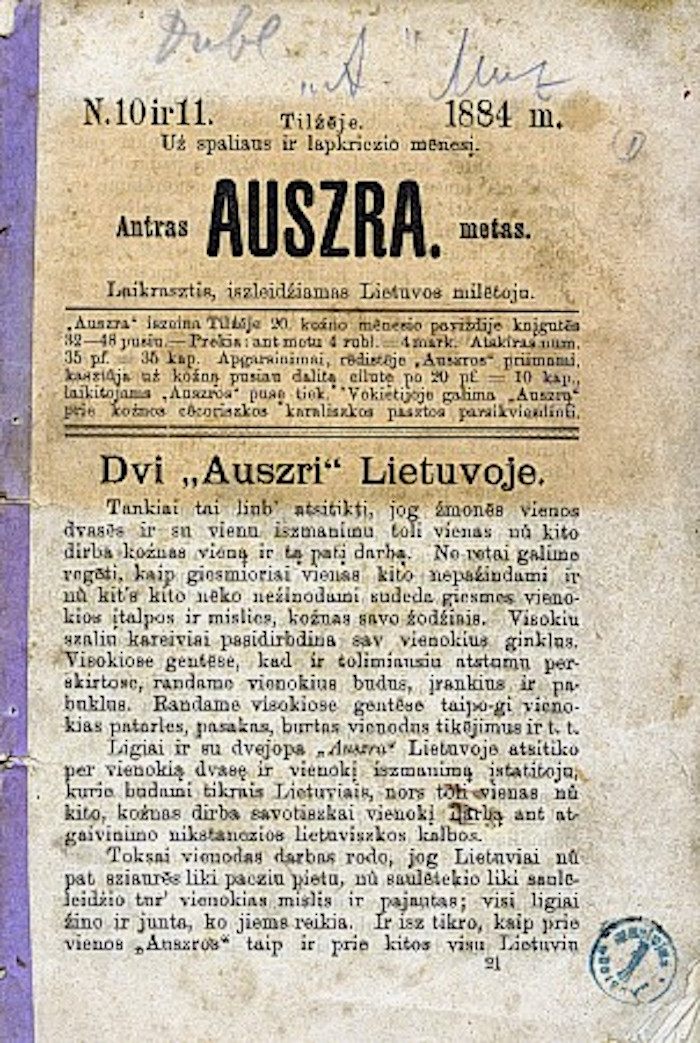

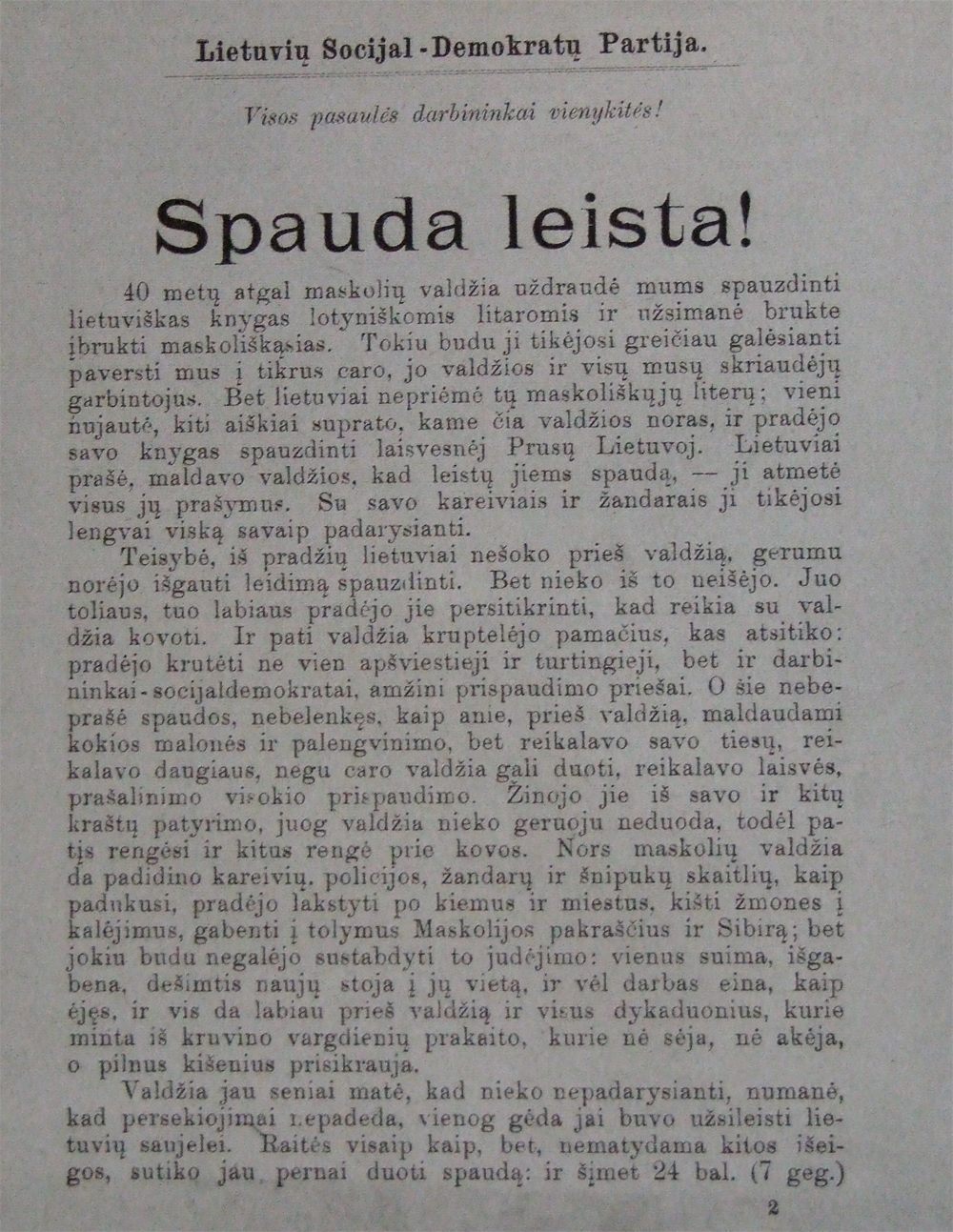

By the 1880s, channeling a growing restlessness, secret newspapers like Aušra—meaning The Dawn—rallied against Russification and whispered of independence.

Lithuanians began organizing choirs and performing secret plays that spoke of the resilience and beauty of Lithuanian language and culture. By the end of the 1900s, “picnic outings”—wherein Lithuanians met to discuss politics among themselves—came into vogue.

The Lithuanian national rebirth was underway.

Father Julijonas Kaspervacivius writes, “the work of restoring Lithuania’s independence began not in 1918 [when Lithuania declared itself a state], but rather at the time of the book carriers. With bundles of books and pamphlets on their backs, these warriors were the first to start preparing the ground for independence, the first to propagate the idea that it was imperative to throw off the heavy yoke of Russian oppression.”

In other words, what had begun as an attempt to assimilate Lithuanians to Russian culture in fact made the region more fiercely independent than before.

By the turn of the century, Lithuania peasants organized local board meetings and petitioned the Russian Empire to end the ban—the Russian government fielded over 100 such requests.

Even in Russia, the ban became unpopular, especially among intellectuals who opposed its wide and often vaguely defined scope. In 1897, Russia’s Council of Ministers first declared the ban a failure; it was finally rescinded in 1904, in an attempt to reconcile minority groups within the Empire during the Russian-Japanese War.

It was, however, too late. Lithuanian resistance to Russia was at a high.

Driven by the national zeal, Bielinis soon began talking more openly of independence from Russia. He became the de facto spokesmen for a Lithuanian patriotism that would provide the force behind the February 1918 Act of Independence of Lithuania.

Bielinis just wasn’t there to witness it: he died in January 1918, a month before independence was formalized.

Today, Bielinis is memorialized not only through stamps and statues, but also through a holiday: the Day of Knygnešys, or the Day of the Book Carrier, which takes place every year on his birthday.

Bielinis has, in many ways, become a symbol of pride both in Lithuania and abroad. He is remembered not only as a national patriot, but also as a hero for those who profess the power of the written word—historical proof that a rag-tag group of rebels armed with books really can triumph over an empire.

* Correction: This story originally identified the opening image as Jurgis Bielinis. It depicts another smuggler, Vincas Juška.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook