The Devilishly Difficult Locks of Dindigul

These unique handcrafted mechanisms are designed to protect homes, confound cashiers, and outthink thieves.

A.N.S Pradeep Kumar picks up a shiny silver key the size of his forearm. He inserts it into a huge lock placed on the counter of his store. Every time he twists the massive key, a ring reverberates throughout the shop.

“This is the bell lock,” he says. “A skilled locksmith in these parts would take two weeks to craft this by hand.”

Surrounded by a sea of shimmering silver and brass, this 42-year-old lock manufacturer and retailer has spent his life and career in Dindigul, a city of two million people in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu. For the past 75 years his family has been part of, and privy to, the secrets of an ancient lock-making industry.

Last August, Dindigul locks received a GI (Geographical Indication) tag, given to unique and authentic indigenous Indian products that can be traced to a specific geographical area and are famed for their quality.

In Dindigul’s case, that geography has always been key. “People turned to making locks [here] because there was an abundance of iron in this region, but water for agriculture was scarce,” says Pradeep Kumar.

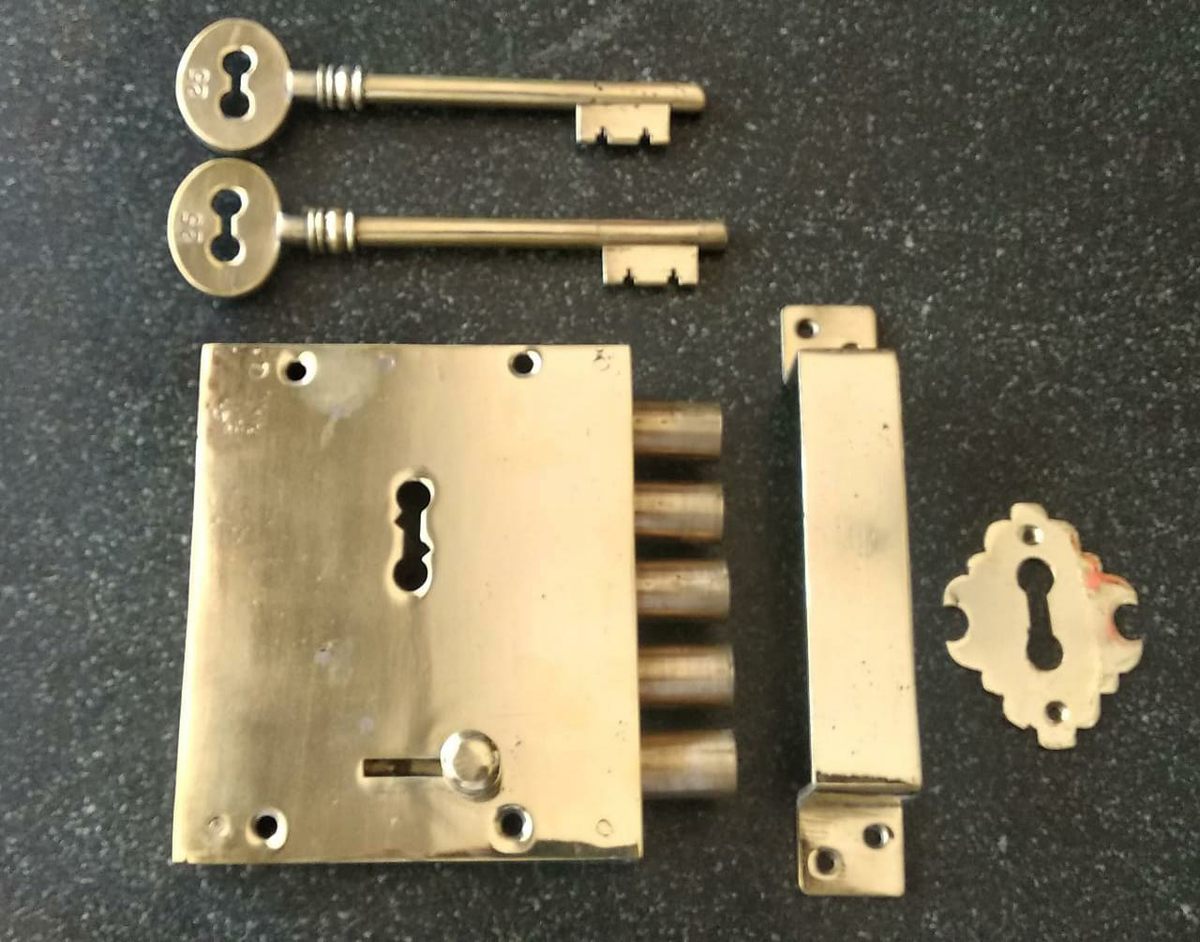

Yet times are changing. Until the 1980s, perhaps 1,800 locksmiths lived and worked in Dindigul. Today, only about 200 practitioners know how to craft a typical Dindigul door lock, also called a bullet lock. It’s a complicated metal contraption, with nine inner levers that operate five cylindrical steel rods simultaneously; the rods latch into place with every twist of the key.

Though demand for these locks still exists—temples, homes, and government offices in Tamil Nadu still use them, for instance—production hasn’t been able to keep up, due in large part to a dearth of skilled labor. Ingenuity has suffered too. At one time the city produced over a hundred varieties of locks. Today perhaps 50 variants exist, only 10 of which are in active production. In just three generations, says Kumar, the intricate knowledge that sustained a city has faded.

Ragu runs a small hardware store called Ragu Hardwares, tucked into a narrow lane on Dindigul’s vibrant market street. There was a time, he says, when he stocked only Dindigul locks. But in an era of electronic surveillance and high-tech security systems, competition from cheaper, machine-made locks—manufactured in China and the northern Indian city of Aligarh—has changed the equation.

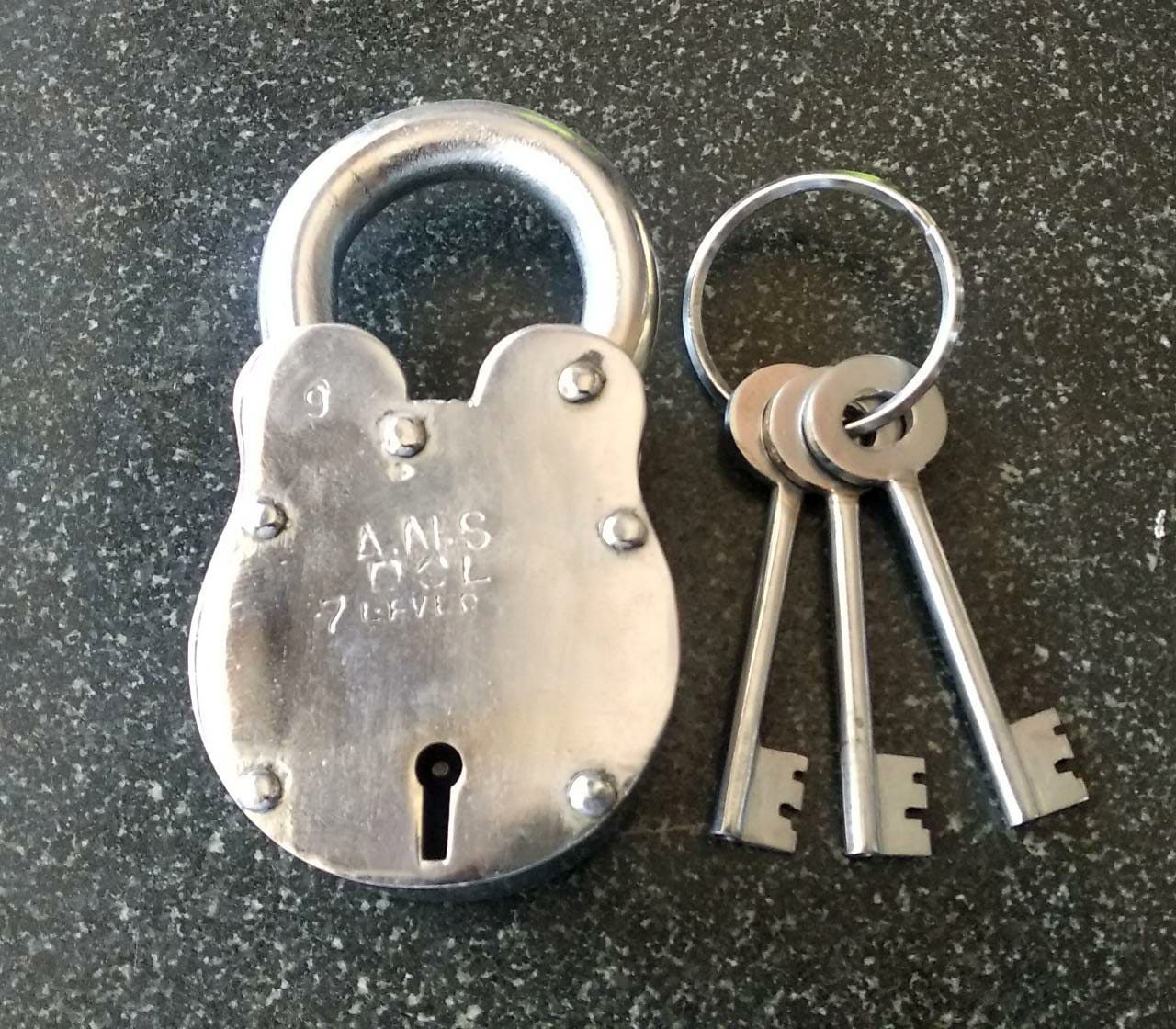

One variety of lock, however, has maintained its popularity here: the maanga poottu, or mango lock. Resembling an ordinary padlock designed in the shape of the mango—a beloved fruit in these parts—its popularity hinges on its durability. Made in all sizes, it can be used to secure homes, drawers, safes, cupboards, and bicycles.

Every mango lock is designed to be opened with what’s known locally as a “female key.” When the key, which has a circular hollow opening at its tip, is inserted into the padlock, the hole latches onto a rod in the lock’s internal mechanism.

Pradeep Kumar describes a customer from Chennai who recently ordered a “nithra” lock—a mango padlock that has two keyholes placed side by side, specifically designed to confuse a thief. If the key is inserted into the wrong hole, the lock jams. The customer wanted his nithra lock to be obscured by two iron plates that slid over the keyholes.

Some mango locks have an iron rod that extends from the keyhole. The lock can be opened only if the rod is positioned at a certain angle; the nature of the tilt is a secret known only to the locksmith and the person who commissions it. “It’s a version of a number combination,” says Pradeep Kumar.

Then there’s the mango button lock, which opens only when you twist the key after pressing a hidden button. There are also padlocks that require two keys of different sizes to open. The second key is bigger, and works only when the smaller one remains inserted in the lock.

“Vichitra” mango locks are among the most fascinating in Dindigul’s history. These locks were built with the natural hierarchy of a family business in mind, at a time when such enterprises were the norm, and flourished in an age when cash registers were never mechanized.

Each Vichitra lock has three keys—one for the cashier, one for the supervisor, and the third for the owner of the company. If the supervisor suspected that the cashier was stealing from the store, he could put his key into the lock, twist it once to the right, then lock the cash register by twisting left. After that, the cashier’s key would no longer work. If the owner wanted to shut out both the cashier and the supervisor, he could do the same thing with his key.

The first Dindigul lock is said to have been commissioned by Tipu Sultan, the 18th-century ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore in southern India, to guard a fort on the summit of a steep hill in the heart of the city. But according to British records, says N. Rajendran, head of the history department at Bharathidasan University in Tiruchirappalli, the Dindigul lock industry didn’t truly spring to life until the 1900s.

“It [is] … likely that Dindigul lockmakers were an indigenous artisan community,” he says. “It’s remarkable how they managed to trademark their craft—establishing their unique brand appeal by word of mouth. It led to a thriving market for these goods across south India.”

Five villages around Dindigul were once a haven for locksmiths, but like the retailers, their numbers have dwindled. Pradeep Kumar speaks fondly of a skilled artisan he worked with for many years: Kothambari Pitchai, who passed away three months ago at the age of 85, after a lifetime of locksmithing. “There was no lock that was too complex that he couldn’t devise,” Kumar says. “To me, his passing marked the end of an era.”

On a blazing hot January afternoon, at the government-run Dindigul Lock, Hardware and Steel Furniture Workers’ Industrial Cooperative Society (DICO), four elderly locksmiths are hard at work in a shop filled with rustic tables and tools, quaint machinery, and heaps of iron, brass, and steel. Each of these master craftsmen makes three to five locks a day, for which they earn about 350 rupees (or $5).

For K. Venkatachalam—the 58-year-old head of the local locksmiths’ union who has 36 years of lock-making experience—the GI recognition brought both joy and validation. “I learned this ancient art at the age of seven, from my father and grandfather,” he says. “It makes me glad to think that people have a better understanding and more respect for what we do.”

C. Murugesan, a 30-year veteran of the industry who also works at the DICO, says it takes mathematical precision to make a proper Dindigul lock. While older locksmiths used mental calculations to drill accurate holes in the outer casing of a padlock—ascertaining the size and spacing of each hole, and how the parts of the inner mechanism should fit together—newer ones require polytechnic graduates to fill that role. Such graduates, they hope, will drive this traditional industry into the future, mechanizing the process of design and manufacturing.

M. Karuppanah, another 58-year-old locksmith at the DICO, demonstrates how the shop’s lock-making process works. First the outer iron casing of a lock is cut with a mold. One-millimeter holes are drilled into it with a precision gear drill. The inner mechanism—the lock’s heart and soul—is assembled by hand, a process that can take days, or even weeks. That’s because the locksmiths design each lock differently, fitting the inner metal grooves and spring pieces together, and lining them up with the keyhole.

The last step is the filing and polishing. Sparks fly from the bed-grinding machine, a contraption with two rapidly rotating wheels that chip away at the metal lock for a smooth finish. (Despite the sparks, no one here wears any protective gear.)

“The [Dindigul] industry thrived because lock-makers were willing to take bold risks when crafting new designs,” Karuppanah says.

Yet some designs, he admits, were perhaps too adventurous. The famed kolaikaran pootu, for instance—aka the murderer’s lock. Legend has it that it was designed to murder a potential murderer. If a would-be killer used the wrong key or tried to pick the lock, a slim knife would pop out from a hidden slit and gouge out his eyes. These locks are now illegal, and haven’t been seen since the 1970s.

Today, other industries—tanneries, textiles, tobacco cultivation—are thriving in Dindigul. Unless a new generation of locksmithing artisans steps up, the secrets of the city’s ancient industry may be locked away in the past.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook