How a Museum Cares for a Giant Chunk of Dried-Out Fat

A conservator shares the nitty-gritty details about taking a fatberg from the sewer to an exhibition.

Andy Holbrook first laid eyes on the fatberg in October 2017, the day before his birthday. A collections care manager with nearly two decades of experience under his belt, he’d been dispatched by his colleagues at the Museum of London to pay a visit to “a slightly baffled but quite amused” team at Thames Water, the local sewage utility, to see about harvesting a slice of the congealed behemoth to display at the museum. “It felt like the most bizarre birthday present ever,” Holbrook says.

This fatberg, allegedly the largest ever hauled from any sewer, threw a famously putrid roadblock in London’s subterranean infrastructure in 2017. Fatbergs are often comprised of a slurry of used napkins, diapers, and other squishy detritus. This particular gloopy mess of discarded oils, fats, and more grew to more than 130 tons, and sprawled 250 meters long. Then, worse yet, it began to saponify—think of plaque hardening along an artery, leaving scant space for the blood to flow. The mass had no trouble clogging the centuries-old pipes under Whitechapel Road.

When the museum’s staff started chewing on the idea of putting a chunk of it on display, Holbrook says, some detractors sniffed at the premise—it had the whiff of a gimmick. But as part of the institution’s City Now City Future programming, which considers the promises and perils of urban life, Holbrook finds that it raises provocative and complex questions about what it takes to keep a metropolis churning, as well as the often-icky logistical challenges that arise when so many people share a space.

Beginning this month, pieces of the fatberg are on display at the museum in a series of nestled vitrines. Many museums employ these boxes to protect fragile objects from visitors, who meddle, accidentally or otherwise, in all sorts of ways—an errant elbow, an uncapped pen, and all hell breaks loose. The fatberg inverts that logic. It’s a slab of an object that spent its entire life marinating in sewer juices, and the hazardous gases that attend them: The boxes are keeping us safe from it.

Atlas Obscura chatted with Holbrook about dangerous collections, trial-and-error, and why the fat-striped lump looks surprisingly celestial.

How did you determine it was safe to interact with the fatberg?

We agreed that we would monitor it at the sewage works. We still had to go through quite a lot of processes to see if this was something we could safely collect, let alone safely display. We wanted to see, if we put it into a showcase in the public gallery for six months, how it was going to behave. Principally, was it going to offgas, let off all sorts of nasty substances that might cause the case to explode, or be a health risk or a fire hazard?

[The sewage facility was] looking at things like methane concentrations, hydrogen sulfide concentrations, carbon monoxide concentrations. They advised us that there basically wasn’t an issue with any offgassing.

You decided to dry it out. Why go that route?

We also looked at possibly freezing or freeze-drying, as well, which we do all the time for a lot of the archaeological materials—things like wood, leather, any organic materials that we find in a wet environment, we freeze-dry. To be honest, we suspected that we would just contaminate all of our equipment. We have a big vacuum chamber that sucks all of the moisture out. We just didn’t think we could ever clean it after we’d done it.

We didn’t know how the fatberg samples would respond—whether they would crumble or fall to bits. It was a bit of a calculated risk. We didn’t have a map for where we were going with this. We just slowly air-dried it out over two-and-a-half months, and found that it retained its shape, it retained its integrity. It did change color: It was a much browner color originally, and it changed to a bony, ivory color. And it did shrink.

Many conservators focus on halting decay, or even restoring things to a more-pristine condition. What was your goal?

Our philosophy was, let’s try and make it safe and usable for the lifetime of this exhibition, which runs through until later in the year. It was more about how you manage the environment safely, reduce the risk for pests, manage the hazards.

Since the fatberg went on view, a fly has hatched and started zipping around in the case. When the object in the case is literally garbage, is that a big deal?

We live in this world where everything on display has to be slightly clinical, and clean and tidy, and dust-free. Certainly, within conservation, we don’t like insects being in there with objects, as a rule. Part of our work is pest management. We’re worried about moths eating our costumes, and woodworm eating our furniture. Almost instinctively, you see a fly in a showcase and you think, oh, there’s a problem here.

But because we’re taking a more sanguine view of the longer-term status of this item, we kind of just let it be there. So far, we’ve only got one fly. If it wants, it’s got a whole fatberg to eat. It doesn’t seem to have any friends. And in fact, it’s sort of added a bit a bit of drama and a bit of sense of place to the exhibit.

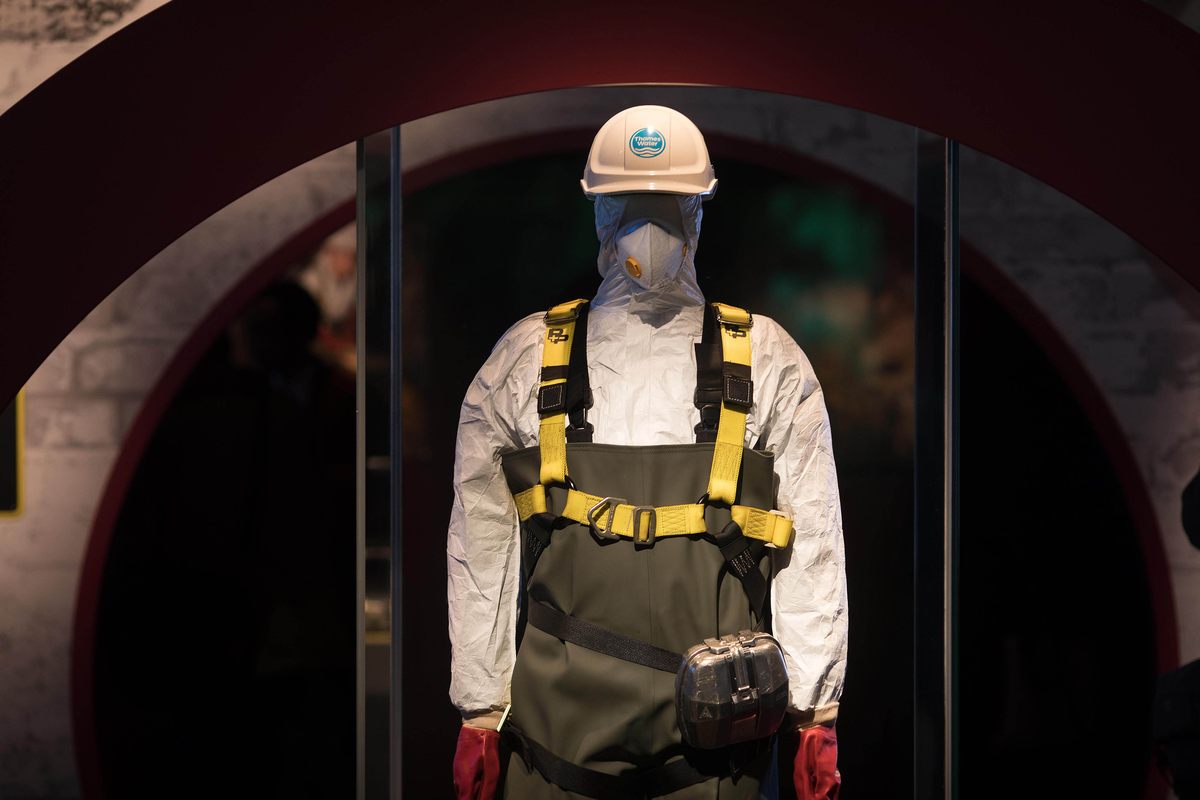

You had to wear a hazmat-style suit to insulate yourself against gases and other risks. Have you been in other conservation situations you’d describe as dangerous?

I have, I’m afraid to say. My job prior to this was working at the Imperial War Museums, so I’ve worked a lot with weaponry and drugs. We have a drug collection here, as well. Lots of 18th- and 19th-century medicine kits, which have things like cocaine, laudanum, morphine. Two of the more recent drugs [include a] cocaine wrapper with no cocaine on it, and also an ecstasy tablet. We have a lot of 20th-century collections with asbestos in them, as well. If you’re working with items like that, you have to be fully suited up.

What kind of gear do you have to wear?

[With drugs], just gloves, so you don’t absorb anything through your skin. The main area where we do wear those full hazmat suits are asbestos. I’ve normally got a bit of a stubble-y beard. One time, when I was working with an asbestos collection, I had to shave my beard off just so I could put the mask on properly and get a good air seal.

From the outside, the fatberg looks a bit like a rock. What’s it made of?

We sent a 200-gram sample up to [the researcher] Raffaella Villa at Cranfield University, and she ran a load of mass-spectrometry analysis. It’s about two-thirds fat and 20 percent ash and grit. Of the fat component, about half was palmitic acid, which you find in palm oil—mainly cooking fats.

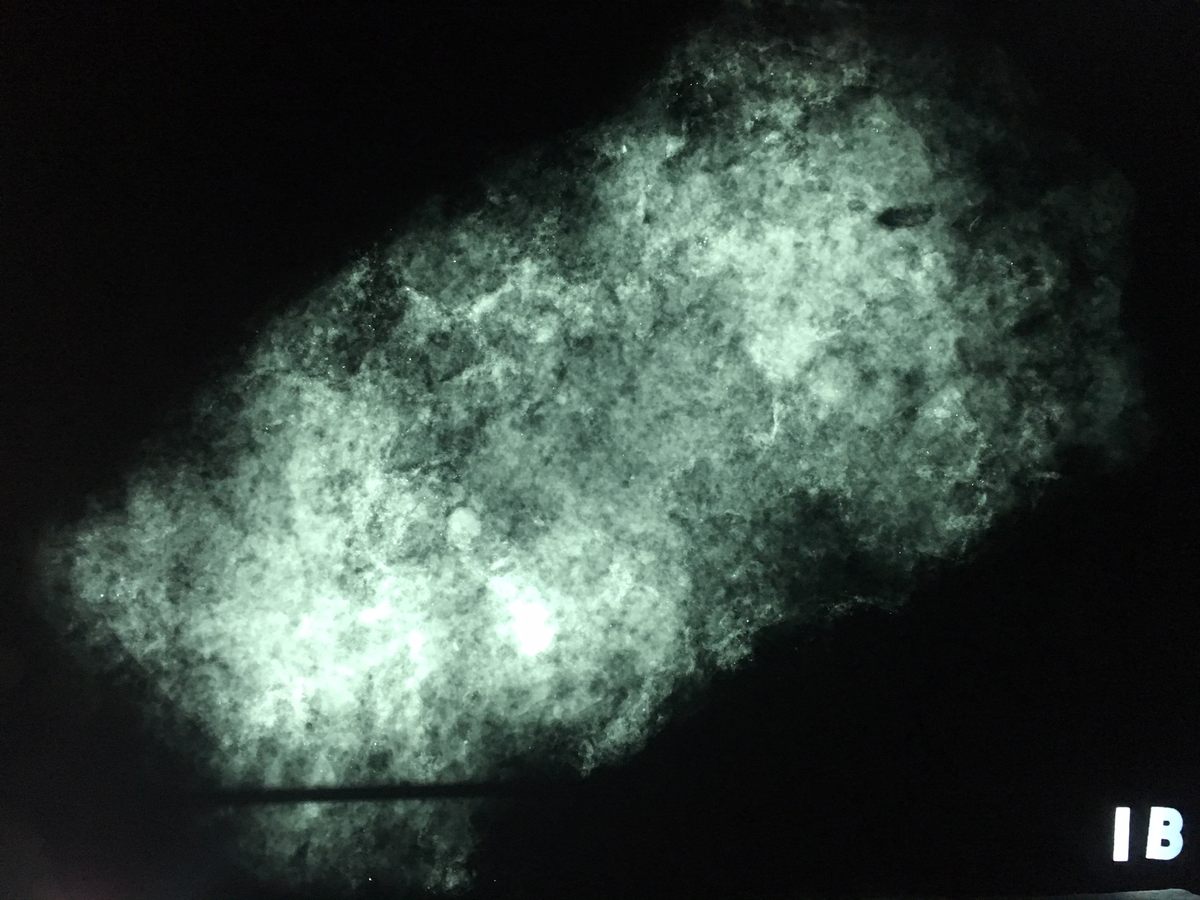

You X-rayed the slice to look out for sharp things that could pose a risk when you handled it. What did you see when you looked inside?

Nothing exciting like gold, or syringes, or bones. [The X-rays] were beautiful, I think. Really, really beautiful. They almost look like nebulae, like pictures from the Hubble Space Telescope.

I’ve seen other samples of fatbergs where it’s almost a matrix of fat and these wet wipes all kind of glued together. The samples we have don’t really have anything like that. They’re pretty much all fats. [On the X-ray], you have this black field and this changing grayscale of the fatberg itself, showing the different densities and everything. What you can see, and the reason that it looks like something in deep space, is that you can see where there are little pinpricks of very bright, high-density particles, which we think are bits of grit. We found quite a lot of grit when we did the analysis. That’s pretty much the only thing you can see—these tiny little bright spots, like stars.

It seems like there was a lot of hands-off time, when the fatberg was drying out. How often did you interact with it?

I was a bit like its surrogate father, really. I would go and check on it every couple of weeks [at Thames Water, or at the museum’s storage facility] and just see if it was drying out, check on the status of the flies, see if there was any mold growth. We obviously tried to keep handling to an absolute minimum, because all the reading about sewage and sewage handling did make us quite nervous.

When you did get up close and personal, how did it affect the rest of your day?

At first, it’s very weird and you’re wary and probably a little nervous. Have I washed my hands enough? Have I taken all the steps I need to? You are very wary, and you’re hypersensitive, I think—if you get a tickly cough, or you just feel a bit tired, you start to try maybe attribute it to the fatberg.

I don’t mean this in a complacent sense, at all, but your exposure to it does normalize. I never had to plan my lunch around it or anything like that. People become pretty cool with it, and even start to enjoy spending time around it.

The fatberg is displayed behind two layers of glass or plexiglass. Can visitors smell anything through them?

You can’t smell it, which a lot of people are disappointed about, actually. People were almost willing it to be a bit more disgusting than it is.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook