Glimpses of Lost Railway Journeys of the Past

A new book collects 33 routes that went off the rails.

They called it “The Big Hill”—4.1 miles of railroad so steep that every mile of track had an inclined spur installed to catch runaway trains. They were staffed 24 hours a day. When a train approached, the conductor would have to go through a series of whistles so complicated that they would assure the spur operator the train was under control. Only then would he flip the switch that allowed the train to continue.

The Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) had promised a route through the Rockies, at least 100 miles north of the border, but the mountains at Kicking Horse Pass were so steep that it was impossible to build a track there that met government standards for railway grade. But as CPR began work on a tunnel through one of the mountains, the Big Hill line was used a temporary fix, designed to “break the government prescribed limit in spectacular fashion,” as Anthony Lambert writes in his new book Lost Railway Journeys from Around the World.

Like the other 32 journeys featured in the book, the Big Hill line is long gone. But the tales and photographs of these defunct routes evoke a time when trains still represented the cutting edge of travel technology. Across the world, Lambert resurrects a bygone world of steam engines, narrow-gauge tracks, and custom monorails that carried cows 10 miles to the seaside.

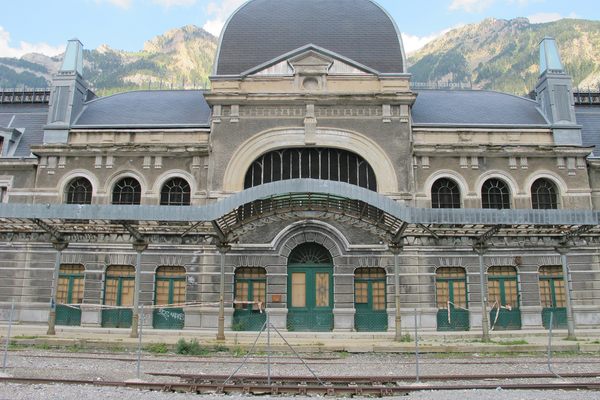

These trains passed through spectacular landscapes and required feats of engineering. There’s the famous Orient Express and the charming Somerset & Dorset Railway, which chugged through the British countryside. There’s the dramatic route that was supposed to cross the Pyrenees, but that never quite lived up to its planners’ ambitions, and the tiny train that used to loop inside the inner walls of Paris. There are trains built to transport gold and trains built to transport pilgrims. Lambert tells of the Bostan-Fort Sandeman line in colonial India, built during World War I to carry chrome ore from a mine in Hindubagh to a British munitions factory. It went through Zhob Valley (now in Pakistan), where the locals would be able to board, and was “one of the few narrow-gauge railways in the world with sleeping cars.” It took 19 hours to travel the line’s 175 miles, at an average speed of just 9 miles per hour. Passenger service continued until 1985.

The lost railways in the book disappeared for all sorts of reasons. They were outcompeted by airlines, better roads, bigger railroads, or speedier subways. Or they were brought down by wars. Or they simply grew old. Sometimes, they were flawed from the beginning.

The Listowel & Ballybunion Railways in Ireland, for instance, were always impractical. The cars were partially bisected by the A-frame monorail track they ran on, which created problems of balance, especially when shipping large items, such as a piano or livestock. The line only made money during the summer, when passengers used it to travel the last 10 miles to the seashore. But it was such an incredible, unusual piece of infrastructure that it became, Lambert writes, “one of the most visited and photographed of Irish railways.”

The line chugging up and down Canada’s Big Hill lasted for 23 years, from 1886 to 1909. Traveling it became a popular adventure in its own right, and when a party of British royals, including the future George V and Queen Mary, took the line in 1909, they rode on the buffer bar at the front of the train while it worked up the hill. Eventually, the CPR finished the tunnel that allowed the railway to carry passengers on a less teeth-clenching ride, and the four miles of what was now called the “old line” were left to history, as so many others have been.

Atlas Obscura has a selection of photographs from Lost Railway Journeys from Around the World.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook