The Frenzy About the Weirdest Continent That Never Existed

Forget Atlantis, the lost land of lemurs had people in a tizzy.

Philip Sclater should have stopped writing in 1858. That’s when he published one of the foundational texts of biogeography, the science that studies the distribution of species and ecosystems across space and time.

Lemur fossils in Madagascar and India

But there was one little primate that didn’t neatly fit into Sclater’s division of the world into six biogeographical realms. He had found fossils of lemurs in both Madagascar and India, even though those places belong to two wholly separate realms. (In today’s biogeographical parlance, those would be the Afrotropical and Indomalayan zones, respectively.)

So he did what other scientists of the day did when faced with similar disconnects: He proposed a vast land bridge that had once linked Madagascar to India. And he gave that hypothetical continent, now swallowed by the Indian Ocean, an appropriate name: Lemuria.

That was in 1864, and ever since, Sclater’s serious scientific work has been overshadowed by his creation—because Lemuria turned out to be one of the weirdest continents that never existed. Perhaps Sclater’s creation arrived at precisely the right time to fill a fertile niche in the imagination. Two-thirds into the 19th century, there were very few real places left to discover. The sudden addition of an entire continent to the map—never mind that it was conjectural and drowned—inspired other scientists (and other, less scientific-minded thinkers) to develop theories about Lemuria that went well beyond explaining the whereabouts of a tiny primate.

Lemuria, the ancestral home of humanity?

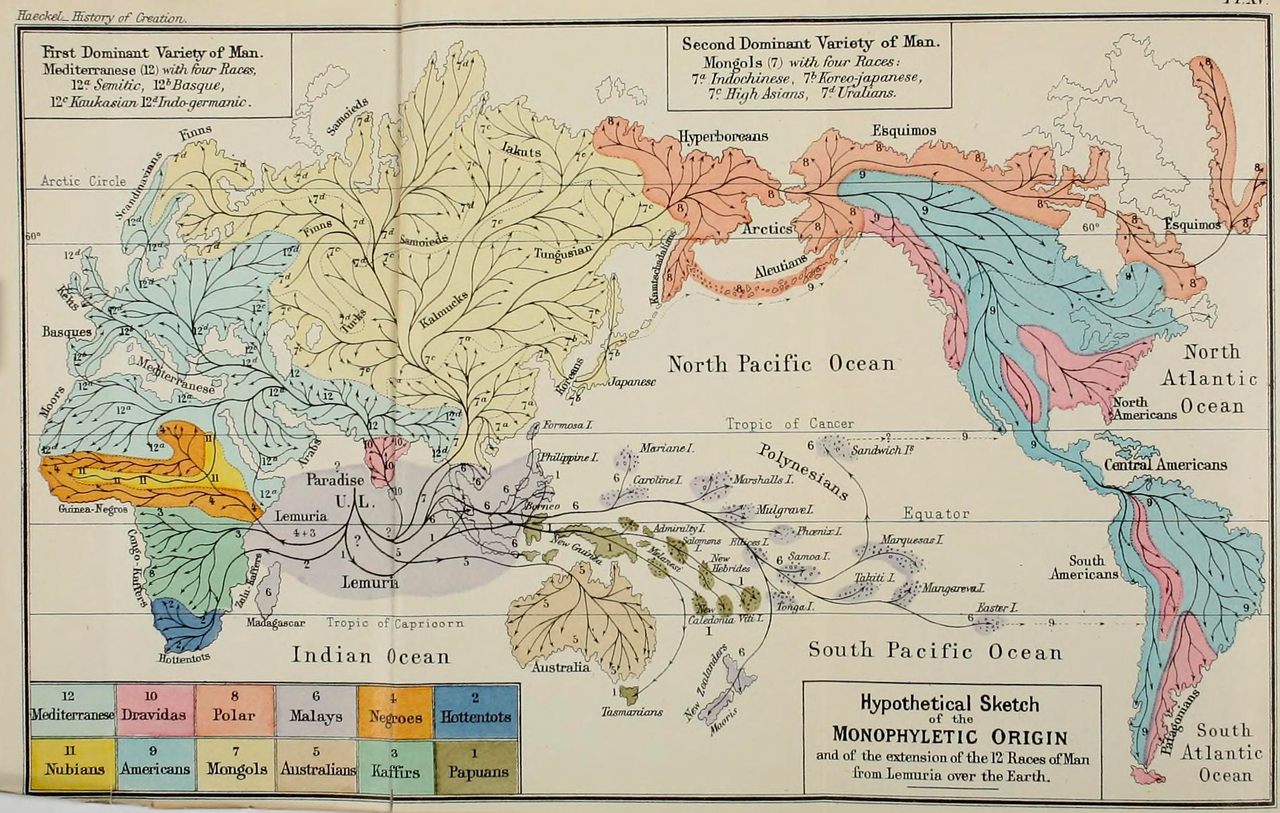

In 1870, German biologist Ernst Haeckel suggested that Lemuria could be the ancestral home of humanity, as a way of explaining “missing links” in the fossil record of early humans. (Rejecting Darwin’s hypothesis of humanity’s African origin, Haeckel had initially favored India as the birthplace of humankind.)

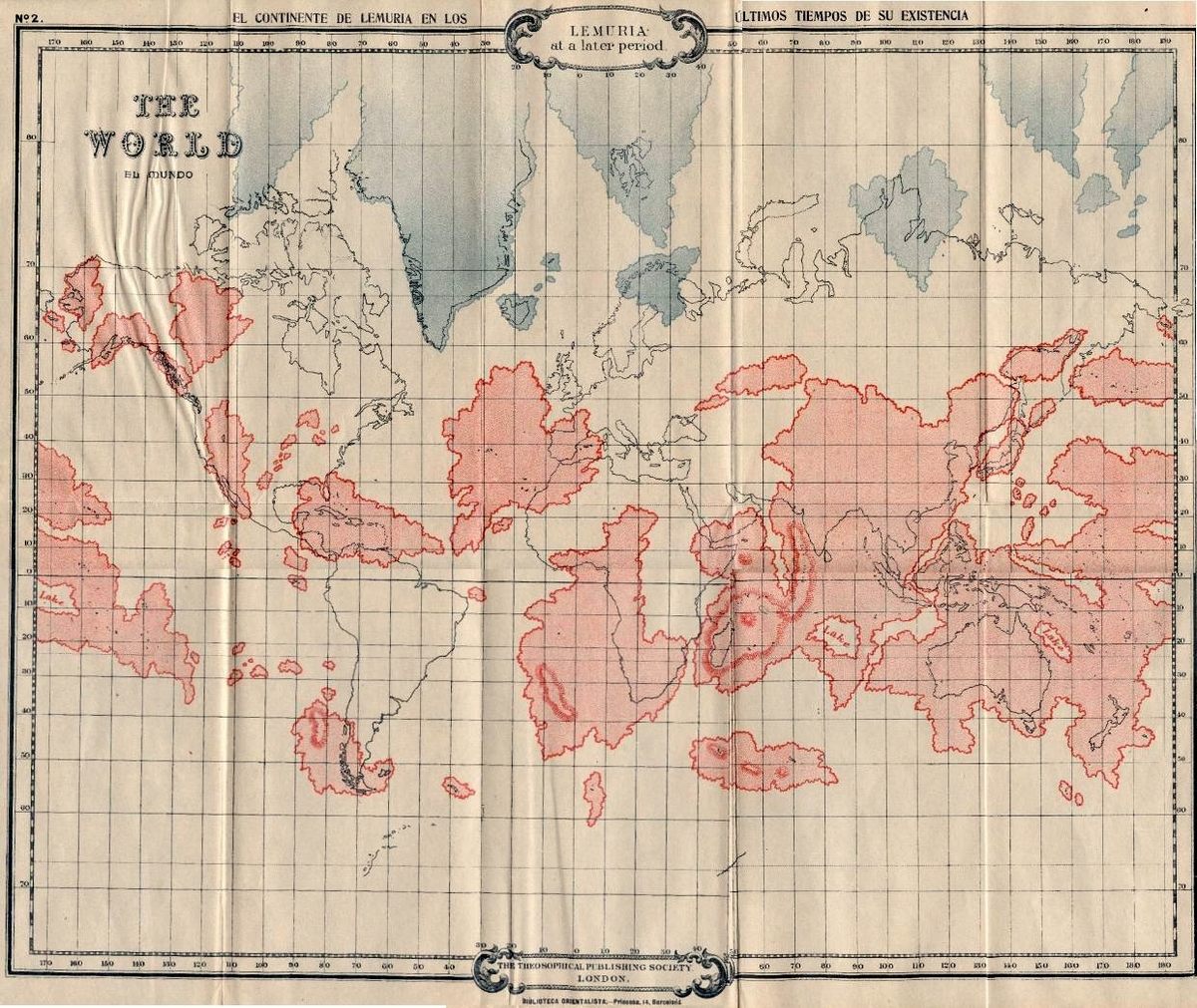

In the 1880s, Lemuria graduated from scientific hypothesis to pseudoscientific fact when Helena Blavatsky, the founder of theosophy, integrated it into her esoteric, proto-New Age belief system. Building on Haeckel’s theory, she proposed that Lemurians were the third “root race” of humanity.

Aided by Charles W. Leadbeater, a theosophist who claimed knowledge of Lemuria via “astral clairvoyance,” William Scott-Elliot elaborated on Blavatsky’s vision of Lemuria and its root races. In The Lost Lemuria (1904), Scott-Elliot placed Lemuria in the Pacific, and described the Lemurians as 15 feet tall, brown-skinned, and flat-faced, with bird-like sideways vision. They could walk backward and forward with similar ease and reproduced with eggs. Interbreeding with animals eventually produced ape-like ancestors to some of the human races.

In India, Lemuria was adopted by some Tamil nationalists and mystics as confirmation of Kumari Kandam, a legendary sunken land first mentioned in 15th-century Tamil literature. Tamil revivalists identified Lemuria with this ancient cradle of Tamil civilization.

The continent’s Tamil name (that is, Kumari Kandam) can be translated as “land of the maiden.” Some speculated that Kumari Kandam had been a matriarchal society where women chose their husbands and owned all property. Kumari Kandam is one of multiple mentions in ancient Indian texts of lands in South India lost to the ocean. Possibly these are records of historical tsunamis and other natural disasters.

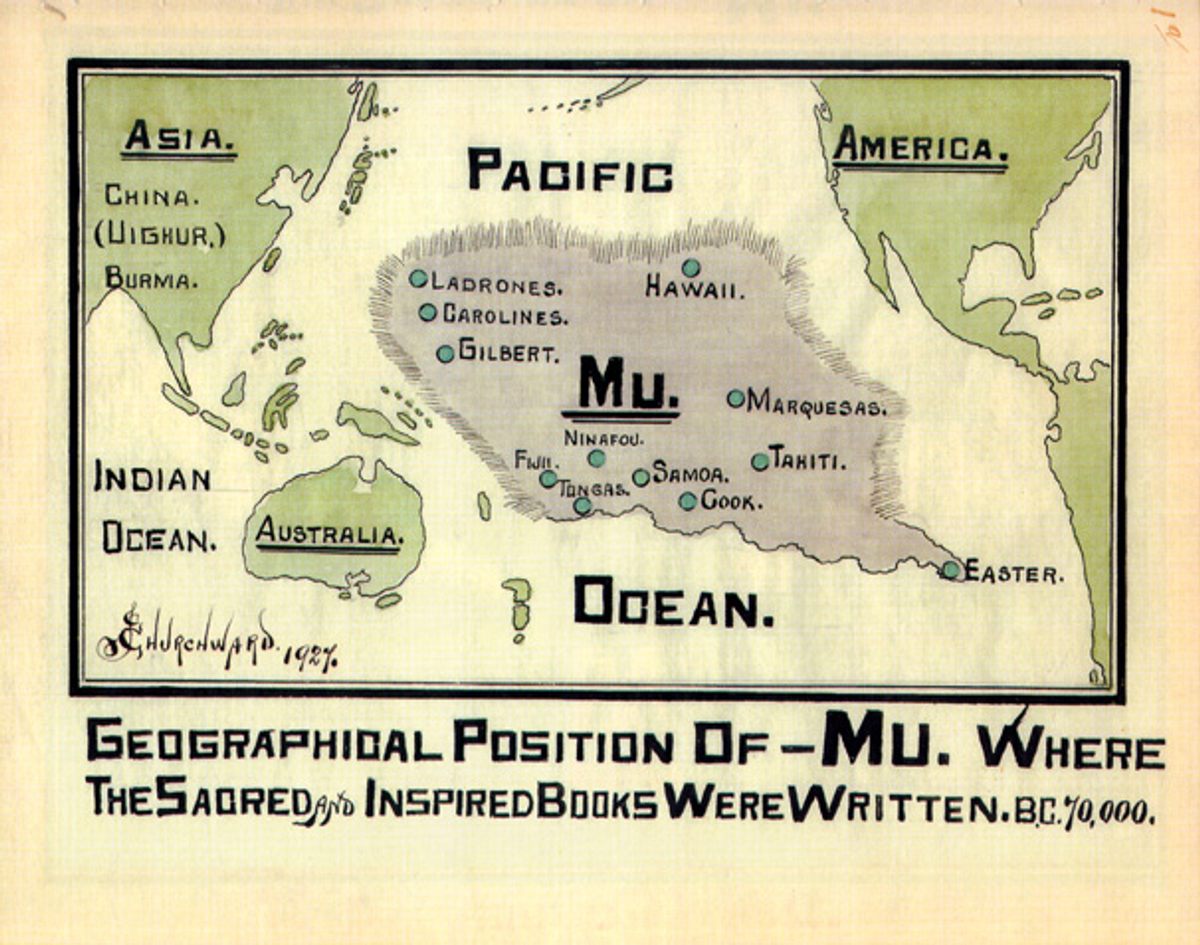

In The Lost Continent of Mu (1926) and subsequent books, James Churchward repurposed the myth of the lost continent and civilization of Lemuria, renaming it Mu and, taking a cue from Scott-Elliot, placing it in the Pacific Ocean.

A jewel-encrusted underground city

In the American imagination, Lemuria became most closely associated with Mount Shasta in northern California, which according to Frederick Spence Oliver (in his 1894 book A Dweller on Two Planets) and other occultist writers was the last refuge of the survivors of sunken Lemuria, who lived there in a jewel-encrusted underground city called Telos.

According to some of the more outlandish theories, other survivors of sunken Lemuria turned to the sea, and became whales, dolphins, and mermaids. Others have walked among humans as shamans and prophets ever since, explaining why many religions are so similar. Sadly, there is no word on whether some Lemurians actually transformed into lemurs.

Lemuria finally fell off the map in the 1960s, when Alfred Wegener’s theory of plate tectonics became widely accepted. Tectonic activity explains continental drift, which eliminates the need for hypothetical land bridges like Lemuria.

As a consolation of sorts, scientists studying plate tectonics found that India and Madagascar had been part of the same continent in the deep past, and not just once but twice: They were neighbors in Mauritia, a Precambrian microcontinent (2.5 billion to 800 million years ago), and in Gondwana, a more recent supercontinent (formed about 510 million years ago). India and Madagascar finally separated about 70 million years ago.

Yet, Lemuria lives on

Scientific Lemuria may be dead, but occult Lemuria lives on. The Kumari Kandam theory remained in history textbooks in southern India’s Tamil Nadu state until the 1980s. In 1981, the state government funded a documentary that tried to reconcile the sunken continent theory with continental drift, and show Lemuria as scientifically valid. New maps of a sunken Tamil supercontinent still surface occasionally, sometimes reaching as far south as Antarctica.

Lemuria is not the only ingredient of the otherworldly cocktail that keeps drawing people toward Mount Shasta, but it is by no means the least. Visitors to the area occasionally report seeing seven-foot-tall Lemurians walking the surface in flowing white robes, supposedly on a break from their subterranean existence.

In the comments section of a local magazine article about Lemurians, someone mentions: “I can tell you the story of a Bay Area child who was told by her parents that if she and her sister wandered off from the car while stopping to get gas in Dunsmuir that the Lemurians would think they wanted to be sacrificed to the mountain and take them away.”

Lemuria also lives on in Ramona, a small town in Southern California and headquarters of the Lemurian Fellowship. Founded in 1936, the Fellowship is a religious organization that transmits the wisdom revealed to its founder by a group of Masters hailing from Mu (the Pacific version of Lemuria).

Reincarnation, karma, and Christ

The Lemurian Philosophy says that if we live by universal laws (including the belief in reincarnation, karma, and the teachings of Christ), we will achieve an advanced stage of civilization. Its guiding principle is balance: spiritually, materially, and mentally. Students who successfully complete first a correspondence course and then advanced training may join the Lemurian Order. The Order supports itself in part by the sale of arts and crafts made by its members.

One of their wooden beakers is in the Museum of Modern Art in New York. That must rank high on the list of weird consequences that Philip Sclater couldn’t have predicted when he came up with Lemuria a century and a half ago.

Weirder still is the fact that “Lemuria” now is used by the British government to describe its tiny territorial holdings in the Indian Ocean. The coat of arms of the British Indian Ocean Territory (that is, the Chagos Archipelago) has the motto: In tutela nostra Limuria, Latin for “Lemuria is in our charge.”

The restless spirits of the unburied dead

A final word on lemurs. These adorable creatures only exist in Madagascar. So what was Sclater talking about? The confusion is the result of a change of definition. Back in the 1860s, the definition of lemurs also included the slender loris, another tiny primate, which does exist in India (and Sri Lanka). While they share some similarities, the species are not closely related, having diverged about 70 million years ago.

Lemurs were named in the 1850s by Carl Linnaeus himself, the founder of the current system of biological nomenclature. Linnaeus got the name from ancient Rome, where the lemures were the restless spirits of the unburied dead. On May 9, 11, and 13, during the festival of Lemuria, the father of the household would rise at midnight to placate the lemures by casting black beans behind him. Those unsatisfied by this nourishment would be scared off by banging bronze pots.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time. Sign up for Big Think’s newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook