‘Mail Art’ Makes a Comeback During Quarantine

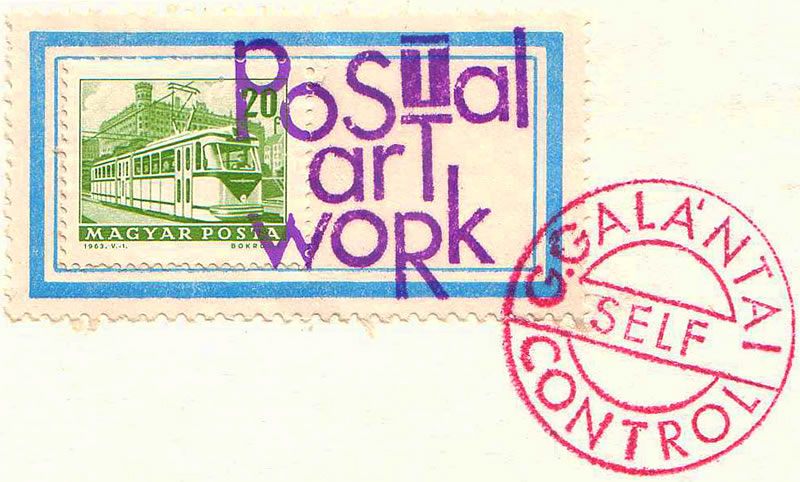

All you need is an idea, an envelope, and a stamp.

In the 1950s, the New York–based artist Ray Johnson pioneered a new form of expression known as “mail art.” The idea was that artists could distribute their work privately, through the postal service instead of through galleries and other exclusive institutions. It’s been observed that Johnson, in some ways, anticipated how the internet and social media would influence the dynamics of the art world. It may be the COVID-19 pandemic, however, that brings his original, analog way of doing things back into vogue.

Artnet News reports that, in this time of social distancing, a variety of artists and patrons are re-engaging with mail art as a safe mode of communal creativity. Nashville-based artist Jason Brown, for example, has called for submissions using a simple prompt: “my view from home.” Brown is open to both real and imaginary renderings of what you see from inside quarantine, so think carefully if you plan on submitting to his project—he’s going to donate the full haul to the Vanderbilt University library. Your submission could one day end up in an art history student’s thesis on visual representations of COVID-19.

On his website, Brown celebrates one of the central tenets of mail art: that absolutely anyone (with an envelope and stamp) can create it. All techniques (painting, drawing, mixed media, and beyond) are welcome, nothing will face a jury, nothing will be sold, nothing will be returned to sender. Brown quotes a simple definition of the form, from the University of Buffalo: “A work of art becomes Mail Art once it is dispatched … ”

Printed Matter, Inc., a New York-based nonprofit purveyor of artists’ books, has captured that roving spirit with a recently launched mail art initiative. Manager Johanna Rietveld says that the organization has received nearly 500 works of art so far, ranging from textiles, to a punny can of SPAM, to old leather book covers that had been removed to allow rebinding. The artists, meanwhile, have included a 101-year-old, a five-year-old, and an incarcerated person, she told Artnet. Printed Matter—which will publish a book featuring a selection of the works—issued a broad prompt: “We live in real time.” Rietveld told Artnet that the prompt refers to “experiencing the moment, moving through life in real time, while also looking ahead to the moment when we’ll be thinking back on it.” Like Brown’s, Printed Matter’s project will function as a kind of living history archive.

Not all curators, however, feel the need to issue prompts to solicit mail art. Jason Pickleman, whose Lawrence & Clark gallery in Chicago has held annual mail art exhibits since 2018, feels that “the less you say the better, and the more authentic the response.” Artists have certainly run with that freedom. About two weeks ago, Tony Tasset sent Pickleman a list of instructions entitled “Burning Man for a Lockdown.” The request? Burn a roll of toilet paper, dance around naked, film it, and post it on social media. Pickleman gladly obliged, though the video was taken off of Instagram “for obvious reasons.”

Pickleman adds that he always follows mail art instructions—and they often carry tasks for the reader to execute—“to the letter,” with one exception: He did not heed the piece of mail art that told him to destroy all mail art, though he appreciated the ambitious, auto-destructive impulse behind the idea. (For the record, Pickleman also receives more traditional, non-instructional works, such as collages—even if one sender did claim to be living on the planet Jupiter.)

While Pickleman’s gallery has showcased mail art for several years—he has been interested in the form since attending a Ray Johnson exhibit in the 1980s—he says that the COVID-19 quarantine has greatly increased the volume of submissions he receives. Johnson, he believes, was “subversive” in the way he was able to circumvent the galleries. For different reasons, Pickleman believes, mail art has maintained this subversive cast by defying the pandemic itself.

Typically, he notes, art is something that can’t be touched, with museum guards in place to remind us. Mail art, meanwhile, is physically handled by its creator, its couriers, and its recipient. There’s a “tactile quality” to the experience that quarantiners can’t find on Instagram. “In this moment of social distancing, where the idea of touch has become so suspect,” says Pickleman, “this idea of absolute physicality has a renewed sense of purpose.”

To get started, choose one of the initiatives asking for submissions—or just choose a friend to send your work to. Whether you’re looking to express all your intense feelings, pass the time, give future historians a hand, or just clear out some clutter, now’s the time to make a masterpiece and have it delivered.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook