The Mystery of Maine’s Viking Penny

The coin is the real deal, but how did it get all the way from Norway?

The story that Guy Mellgren told about the curious silver coin began on the shores of Maine, where he met a stranger named Goddard. In the fall of 1956, Mellgren and Ed Runge, a pair of amateur archaeologists, had come in search of the most basic of coastal dig sites—a shell midden—when they happened onto a more unusual discovery.

Goddard had invited them to explore his shoreline property, and there, on a natural terrace about eight feet above the high tide line, they found stone chips, knives, and fire pits, along with an abundance of other unexpected artifacts. Each summer for many years, Mellgren and Runge returned to excavate the “Goddard Site,” with little help from professional archaeologists. In the second summer, they produced the coin.

For two decades, based on an analysis by a friend in a numismatics club, Mellgren described it as a coin minted in 12th-century England, and no one questioned that identification. The discovery should have been noteworthy—there’s no good explanation for how a medieval English coin could have crossed the Atlantic—but Mellgren never sought wider attention for the find. It was a curiosity to show off to friends and his son’s classmates, until, in 1978, a scrappy regional bulletin published a picture of the coin and an article titled, “Were the English the First to Discover America?”

That picture found its way to a well-known London dealer, who recognized at once that the coin could not have come from England. Two weeks after Mellgren died, the coin’s reidentification swept into the news. It was a Norse penny, made between 1065 and 1093—evidence for Viking contact with North America centuries before Columbus.

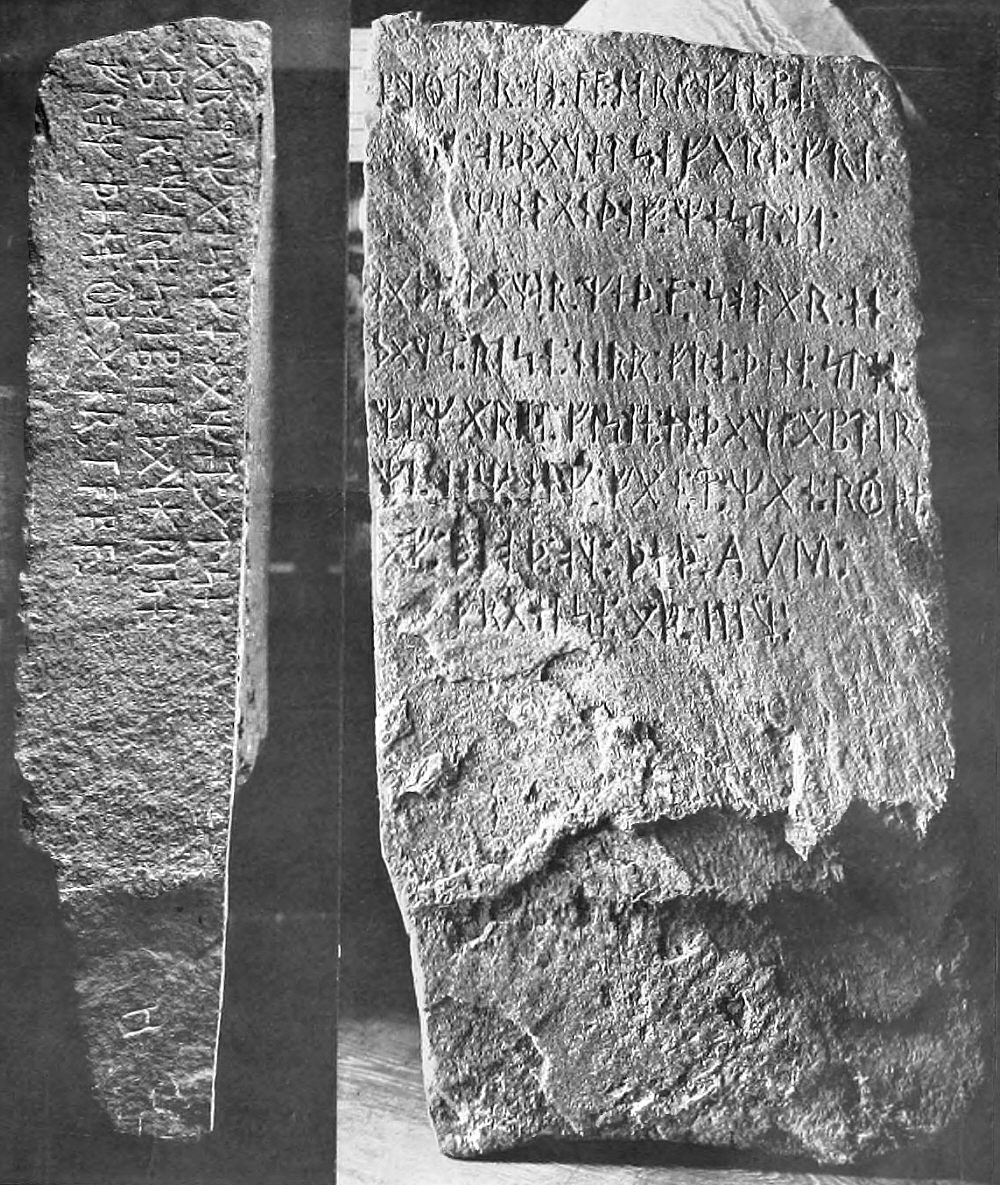

All of sudden, experts from around the world began taking a careful look at the details of Mellgren’s story. Of many objects purported to prove a Viking presence in North America, only the artifacts painstakingly excavated at L’Anse aux Meadows, in Newfoundland, have stood up to investigation. The rest—the Beardmore relics, the Vinland Map, the notorious Kensington Rune Stone—are all considered hoaxes.

Since 1978, no one has questioned that the Mellgren coin is an authentic Norse penny, made in medieval Scandinavia. But 60 years after Mellgren’s find, archaeologists and numismatic experts are still asking how in the world this small, worn coin got to Maine.

On February 6, 1979, Kolbjørn Skaare, a Norwegian numismatist with a tall, wide forehead, walked into the Maine State Museum to see the coin. Just a few years earlier, he had published Coins and Coinage in Viking-Age Norway, a doctoral thesis that grew from the decade-plus he had spent as a keeper at the University of Oslo’s Coin Cabinet. The first specialist to examine the coin in person, he had just a day with it before Bruce J. Bourque, the museum’s lead archaeologist, had to address the national press.

Skaare saw “a dark-grey, fragmentary piece,” he later wrote. It had not been found whole, and the coin had continued to shed tiny bits since it was first weighed. A little less than two-thirds of an inch in diameter, it had a cross on one side, with two horizontal lines, and on the other side “an animal-like figure in a rather barbarous design,” with a curved throat and hair like a horse’s mane. In his opinion, it was an authentic Norwegian penny from the second half of the 11th century.

The mystery centered on its journey from Norway to Maine. It was possible to imagine, for example, that it had traveled through the hands of traders, from farther up the Atlantic coast, where Norse explorer Leif Eriksson was known to have built a winter camp. If the coin had come to America in the more recent decades, the hoaxer—presumably Mellgren, Runge, or someone playing a trick on them—must have been able to obtain a medieval Norse coin.

Medieval Norse coins aren’t an unheard-of rarity. In 1879, farmers in a potato field in Gressli, Norway, had discovered a hoard containing 2,301 coins from the reign of Olaf the Peaceful, the period Mellgren’s penny dated to. Many of those coins were exact duplicates of each other, and the University of Oslo had sold off the extras between the 1880s and the 1920s.

But the Mellgren coin isn’t quite like the ones from the Gressli hoard, which have been described as looking like they’re newly minted. The Maine penny was much more worn, and not an exact duplicate of any coin in the university’s collection. In the 1970s, many experts were inclined to believe the coin was a genuine discovery.

Edmund Carpenter disagreed. Carpenter was an anthropologist and archaeologist known for his films of remote tribal life from the Arctic Circle to Papua New Guinea, and his work at the University of Toronto with the media thinker Marshall McLuhan. From the 1970s on, Carpenter lived as a sort of gentleman intellectual, teaching intermittently and supporting other filmmakers through the Rock Foundation, a charity set up by his wife. He couldn’t believe the credulousness of his colleagues about the Norse penny.

The year Mellgren had found the coin, 1957, was “a bumper year for Viking fakes,” Carpenter wrote in a 2003 article about the coin, published by the Rock Foundation. The year before, Hjalmar Holand, one of the most insistent defenders of the widely debunked Kensington Rune Stone, had published Explorations of America Before Columbus. The same year of Mellgren’s find, writer Frederick J. Pohl* published Vikings on Cape Cod, and a London book dealer started showing around the Vinland map, said to be a 15th-century document of the Vikings’ full knowledge of the globe, but quickly suspected to be a fake. In Holand’s book, he described the Viking Thorwald Eriksson catching sight of Maine’s Mount Desert Island—just across the bay from the Goddard Site.

“Am I alone in finding such a coincidence remarkable?” Carpenter wrote.

Mellgren, he noted, in addition to his archaeological hobby, collected coins and worked part-time at an auction house, which might have given him access to a Norse coin, or at least connections to people who could procure one. Plus Mellgren had an interest in pre-Columbian contact and, like so many of the known Viking hoaxers, Scandinavian roots. He fit the profile.

The idea that Vikings reached the Americas before Columbus goes back to Icelandic sagas that describe journeys west from Greenland to a lush land of grass and grapes. For centuries these were considered only stories to all but a handful of enthusiasts, among them 19th-century Scandinavians who settled in America. Fiercely proud, they relied on these stories to defend their claim to their new country, often in the face of discrimination and scorn from earlier, Anglo-Saxon migrants. They believed the old sagas to be true and wanted evidence to prove it.

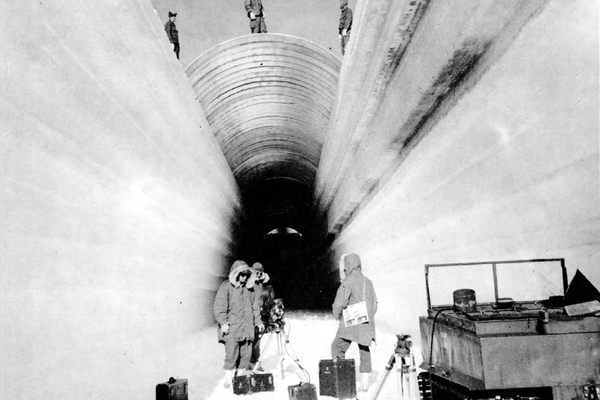

In 1960, Helge Instad and Anne Stine discovered the archaeological site at L’Anse aux Meadows, and over years of excavations produced small artifacts—a pin, a whorl, a whetstone—that tied the site to Vikings. By the time experts identified Mellgren’s penny as Norse, archaeological evidence had already given those tales of ocean-crossing Vikings a toehold in North America.

In hoaxes and other overinterpreted archaeological finds, usually “the hopes outrun the evidence from the very start,” writes archaeologist Stephen Williams in Fantastic Archaeology. But in this case, Mellgren didn’t try to attract attention to the penny. Whatever hopes he had about the significance of his find, he kept them quiet.

“It’s reasonable to suspect that the Norse penny was a plant,” says Bourque, who only recently stepped down as the Maine State Museum’s chief archaeologist. “The balance of the evidence argues it’s an honest find.”

Just this past November, in the Journal of the North Atlantic, Svein H. Gullbekk, a renown numismatist at the University of Oslo and a former student of the coin expert Skaare, took a closer look at the possibility that the coin had come from the Gressli hoard or another notable assemblage of Viking coins. “The pennies of this type, class N, are rare by any standard,” he says. In the paper, he notes that of the hundreds of Gressli coins sold, only 41 were class N pennies, characterized by the orientation of the head design, and all were known from the university’s collection, unlike Mellgren’s. Other major finds contained no pennies of this type, and the class N pennies from smaller finds can all be accounted for.

Based on this process of elimination, “the Norse penny cannot have originated from any recorded Norwegian hoard or single find,” Gullbekk writes. In his view, the circumstantial evidence points to it being a genuine find (even if it does not establish how the coin got there to be found).

There’s unpublished evidence, too, that helps shore up the case. More than a decade ago, Bourque sent the coin for Raman spectroscopy, which, he says, “demonstrated fairly strongly that the coin lay in a horizontal position in the site for a very long time indeed.” The test showed that the corrosion on the coin was consistent with water trickling down around the metal over time, and with other signs of its having been buried for centuries. The wear and tear on the penny, this shows, had not been faked.

After Mellgren’s coin was identified as Norse, the Maine State Museum sent a team of professional archaeologists to the Goddard Site to better understand the context the coin had come from. While no other Norse artifact has ever been found there, the site did hold surprises—artifacts attesting to an explosion of trade contact between Native American groups, stretching from the eastern Great Lakes up to Labrador. At the same time the coin shows up, for instance, archery first appears in the region.

“The site has an unspeakably dense concentration of archers,” says Bourque. Excavations have turned up thousands of arrowheads, along with mounds of pottery sherds and stones that come from hundreds of miles away. “It’s off the charts,” he says. “The real mystery is—what the hell is going on at the site at the time?”

To Bourque, the coin is a clue in this other mystery. All sorts of objects that seem out of place in 12th-century Maine show up in this one spot, as if it were site of a pre-Columbian World’s Fair for northeastern coastal America, from Lake Erie to Newfoundland. Unlike the sagas—all story, little evidence—this site is full of interesting evidence in search of a story.

* This story was updated to clarify that Frederick J. Pohl, the writer of Vikings on Cape Cod is not sci-fi writer Frederik Pohl.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook