The Remote Mexican Restaurant Reviving Jalisco’s Forgotten Cuisine

Maru Toledo and the Mujeres del Maíz are putting history on the plate.

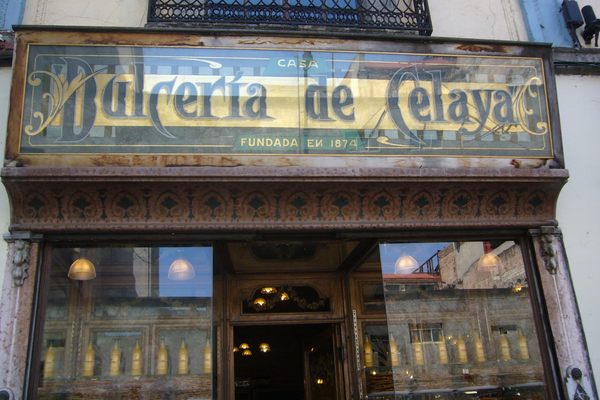

Entering Maru Toledo’s Santina de Covadonga restaurant on a hot, dry day feels like traveling back in time. Visitors who walk up to the gate, dirt crunching under their feet, will likely encounter a dog lazing about and bougainvillea waving gently in the breeze. After passing through the 19th century–style kitchen, filled with dark-red earthenware pottery, old cookbooks, and the smell of smoke, they’ll sit beneath a tin roof and watch as women use pre-Columbian tools to make tostadas raspadas (“scraped” tostadas), grinding corn with a metate and cooking with a traditional firewood stove known as a tecuil. Everything, from the menu to the equipment to the décor, is meant to evoke the historic, nearly-forgotten traditional kitchens of Jalisco.

“We basically cook recipes that are almost extinct, that almost no one prepares anymore,” says Toledo, the restaurant’s head chef and founder.

The restaurant is just one part of Toledo’s mission to uncover the roots of Jalisciense cuisine. Growing up in the Guadalajara, Jalisco’s largest city, she often had questions about food history, but rarely found satisfactory answers. “People didn’t pay attention to traditional food,” she says.

Rafael Hernandez, a Jalisco native and the chair of the department of world languages and literatures at Southern Connecticut State University, agrees. “Most Mexicans imagine that the way they eat is the way pre-Columbian societies ate,” he says. But they “are not even aware that the food we’re eating today is food that was invented in the ’20s.”

Despite being from Jalisco, Hernandez says he was surprised when he came upon Toledo’s cookbooks and research. Compared to states like Puebla and Oaxaca, whose cuisine has received extensive attention, he says there’s still very little published about Jalisco’s indigenous foodways.

Toledo wanted to change that. Her work began at Guachimontones, an archaeological site that dates back to around 300 BC. Although archaeologists had found fossils of purslane and amaranth among the remains of what seemed to be a grand civilization, very little was known about the area’s inhabitants.

To find answers, Toledo consulted Phil C. Weigand, the archaeologist who led most of the modern investigations into Guachimontones. Weigand helped provide insight into the area’s history and culture, and referred her to additional reading. But eventually Toledo needed to move beyond the page and into Jalisco’s kitchens.

“Dr. Weigand told me that my best answer to these questions was in the field,” Toledo says. “I had to do my investigation in the country, to talk to and work directly with the people.”

Toledo has spent the last two decades traveling around the state, to municipalities like Ahualulco de Mercado, Tlajomulco de Zúñiga, Tuxpan, Mascota, San Sebastián del Oeste, and, most recently, Magdalena. As a result of her fieldwork, she has acquired and tested more than 1,000 recipes and published 28 cookbooks—the most recent of which will be published next month.

Toledo’s research has unearthed recipes and ingredients that span Jalisco’s diverse culinary heritage—which extends far beyond its most well-known star, birria. The state has 125 municipalities, each with its own culinary characteristics and traditions, but according to Toledo, most people from Jalisco don’t know the full extent of these offerings.

“[Most] people in Jalisco remember basically five or six dishes, but really there is much more than that,” she says. If you were to put a compass in the center of Jalisco and draw a circle, she explains, within that circle are all five of the standard climates that exist in Mexico. This allows the state to have a wide variety of both ingredients and dishes.

She points to the municipality of Mixtlán, where there’s a region that produces what Toledo describes as “a delicious mineral water” that residents of the area collect and combine with sugar, lemon juice, and sometimes chia seeds to create a beverage for special events. In Etzatlán, she says they used to collect wild plants such as tingueras, a berry that Toledo describes as a black strawberry; princecua, a fruit similar to a capulin cherry; and the flower of San Juan, a white flower with a pleasing aroma that was used to imbue that smell into desserts such as rice puddings. While these plants still exist today, they grow only in extremely remote areas and are difficult to find.

To bring these ingredients and dishes alive, Toledo turned to the local women who knew them best. She assembled the Mujeres del Maíz, a collective of women chosen primarily for, as the name implies, their expertise working with corn as well as their knowledge of traditional recipes from their respective areas of Jalisco.

At Santina de Covadonga, Toledo and the Mujeres del Maíz prepare dishes using pre-Columbian ingredients like amaranth, purslane, avocado, and peanuts, as well as a variety of chiles and flours made from local grains that echo those used centuries ago. Diners can sip corn-based atole and eat a mixture that combines jocoque—a “sour milk” sauce similar to sour cream—with green chiles or a green paste made primarily from pumpkin seeds. As she cooks, Toledo notes that farmers used to wrap this mixture in corn husks with tortillas for lunch when working in the fields.

Toledo says her main goal with the project is not just research, but to generate employment for local women. She brings the Mujeres del Maíz with her to events around the country, giving them the opportunity to leave their home villages and learn new (to them) traditional cooking methods while sharing their own. More than just seeing the world beyond their homes, the women also realized, as Toledo puts it, that they could earn more than in a typical domestic job and potentially open their own restaurant. One of the women has already set up her own business with Toledo’s help in Santa Cruz de Bárcenas.

Despite having one foot in the past, Toledo is still plagued by problems of modernity. In addition to the impact of COVID-19 on the women and some of their businesses, many people around Santina de Covadonga have rented out their land to farm agave, rather than corn, with a devastating impact on the area’s vegetation. While Toledo uses many pre-Columbian techniques in her own cooking, she sometimes incorporates colonial and modern influences, all the while focusing primarily on the naturally available ingredients.

“Nature does her thing and changes the menu for us,” says Toledo. “We just flow with nature. What you see is what you cook with.”

Translation assistance provided by Solomon Behar and Emily Goldman.

Oil-Based Salsa

Published in Pica y Sabe ¡Lástima que se Acabe!, courtesy of Maru Toledo

Ingredients

- 1/2 pound Yahualica chiles de arbol, stems removed

- 2 cups corn oil

- 1 ounce toasted sesame seeds

- 1 ounce roasted peanuts

- Salt to taste

- 1/2 teaspoon cumin (optional)

- 1 garlic clove (optional)

Instructions

-

Heat the oil until hot but not smoking. Fry the chiles until the color changes without burning them. Remove them quickly from the oil and let both cool separately.

-

Blend the chile peppers, sesame seeds, peanuts, and salt with a little warm oil. Season with half a teaspoon of cumin and a garlic clove (optional).

- Store in a glass container for up to 6 months and keep away from the heat. Serve with almost any Mexican dish, from quesadillas to carne asada to tacos.

Notes and Tips

Yahualica chiles are produced in only 11 municipalities in Jalisco and Zacatecas. The chiles are sold dried in local markets, but can be purchased in many places throughout the U.S. and Europe as dried chiles de arbol. Pair this chile with a two- or three-year aged tequila.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook