The Grandeur of Old Masonic Temples Also Makes Them Vulnerable to Fires

They’re hard to reuse, and can be quick to burn.

The fire broke out around 10 p.m. on October 7, 2019, and burned straight through the night. By the time it was extinguished early the next morning, the nearly century-old Masonic Temple in Aurora, Illinois, had been scorched beyond hope of repair.

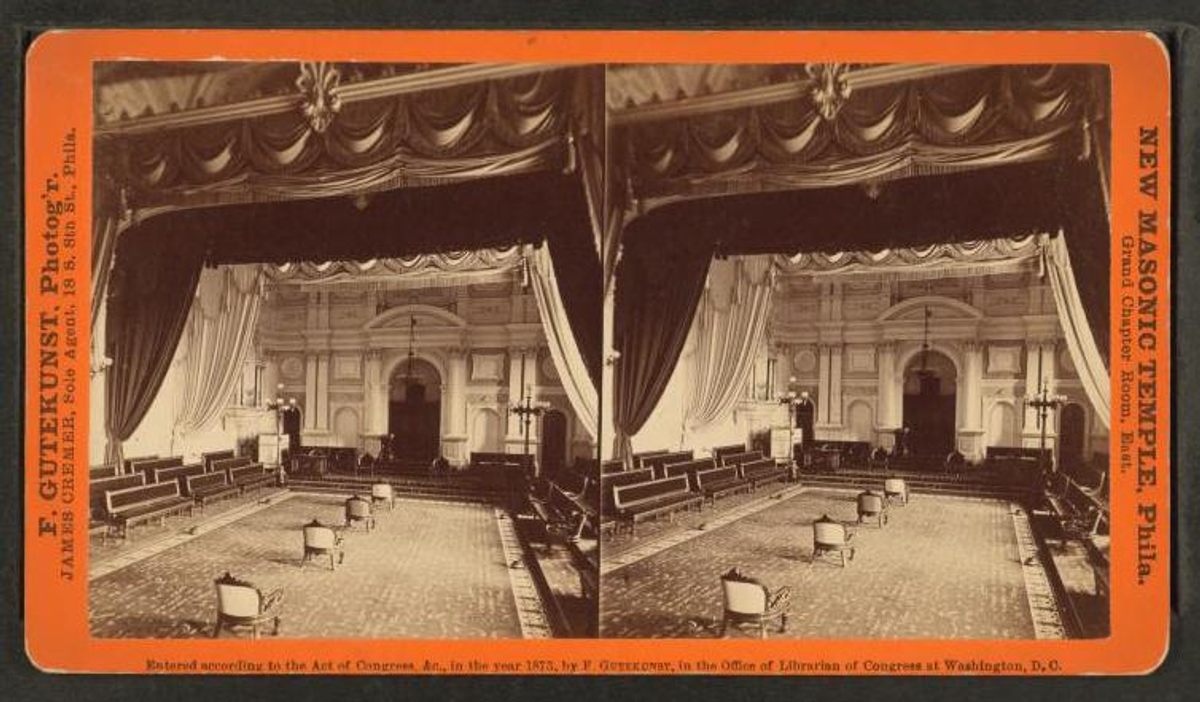

Fires that erupt in Masonic buildings can be stubborn, because some architectural hallmarks of the structures make them easy targets for flames, as well as tough places for firefighters to wrangle a blaze. For one thing, the interiors tend to be pretty cloistered. Temple buildings have relatively few windows, and none that open up into the ceremonial anterooms that form the heart of these structures. “They’re not quite like anything else: They’re kind of like theaters; they’re kind of like church spaces,” says William D. Moore, director of the American & New England Studies program at Boston University, who studies fraternal organizations in America and wrote the book Masonic Temples: Freemasonry, Ritual Architecture, and Masculine Archetypes. “What’s going on in the lodge rooms is supposed to be private and secret,” Moore says, so there are few portals to the world outside.

Those spaces are also often outfitted with flammable decor, Moore adds. They may be draped with ornamental banners, or stuffed with upholstered wooden chairs and home to grand, ceremonial staircases that fires can easily scale. Aurora Fire Marshal Javan Cross told the Chicago Tribune that the building’s design foiled firefighters’ attempts to snuff out the blaze: They had to funnel water from the above, blasting it from the top of the high-ceiling space. “Normally in a fire, we can shoot water through open windows, but there isn’t many, when you think of the square footage of the space,” Cross said. “Even though some windows were broken, we couldn’t get a tremendous volume of water to hit anything that was burning.”

The other trouble was that the 50,000-square foot Aurora temple, like many other Masonic buildings, had slid into disrepair over the years, as fraternal membership dipped from its 20th-century peak, brothers grew older, and the societies found themselves with massive structures they couldn’t comfortably pay for or maintain. The Aurora building, whose cornerstone was laid in 1922, when the lodge was 1,000 members strong, had a second life as a banquet hall and catering hub before sitting vacant for about a decade, the Chicago Tribune reported. (In its Masonic days, the facility was home to a drill room, game room, and 500-person dining hall.) Aurora Fire Department spokesman Captain Jim Rhodes told the paper that the crew had worried that the disused structure was structurally unsound and unsafe to enter once it was aflame, so they battled the fire from the outside instead of sending teams in.

Freemasonry, which traces its roots to centuries-old European guilds of craftsmen, is one of many fraternal organizations that enjoyed big popularity in the United States. The group’s modern history is a little jumbled, but the earliest Masonic organizations in America date to the 1700s, and members still gather for rituals and other activities that celebrate and cement fellowship. (In 2017, there were 1,076,626 full members, according to the Masonic Services Association.) Masonic buildings went up in a flurry between 1870 and 1930, which Moore calls the “great Temple-building period.” During that stretch, “every community had one, at least one,” Moore says.

At first, they were humble—maybe a second-floor rental unit above a bank or a dry goods store. Then, as the groups got wealthier, they commissioned their own purpose-built spaces and installed commercial tenants on the first floor to keep revenue trickling in. Around 1900, Moore says, many of the temple organizations dreamed of bigger buildings that were devoted solely to fraternal functions, and also sent a clear visual message: These were impressive clubs, full of impressive men.

Much as churches sometimes jostled to build the biggest spire in town, there was a premium placed on having a handsome, respectable, institutional-looking Masonic building that evoked the gravitas of, say, a courthouse. In early 20th-century, Freemasonry “was a kind of civic religion that represented bourgeois respectability,” Moore says. “It was supposed to be this organization that represented all the best people in the community, and that’s why the buildings end up looking like civic buildings.” (Many Freemason organizations were exclusively white; several other branches, including Prince Hall Freemasonry, which dates to 1784, were run by men of color.)

The grand construction was a kind of self-mythologizing, Moore says, and also a recruitment tool: “You want the people who are thinking that they’re going to join a fraternity to think you’re the best and the strongest one, with the most attractive building.” Membership had been swelling for years, Moore explains, so the organizations thought they’d need to keep graduating to bigger buildings. Detroit outgrew its first purpose-built Masonic temple in just 20 years, and replaced it in 1926 with the largest Masonic temple in the world, write journalists Alex Lundberg and Greg Kowalski, in their chronicle of the building. The 14-story, 1,000-room behemoth sprawls more than a million square feet. Many of the buildings proved to be way too big. “Even before the Depression hits in 1929, people are feeling the economic pinch, so membership starts to level out,” Moore says. “These buildings that they’ve built expecting that the fraternity is going to continue to grow end up being too large for them.”

Many fraternal buildings are facing the same problems today. “There are underutilized Masonic temples all over the nation, all over the state,” Lisa DiChiera, director of advocacy at Landmarks Illinois, told Curbed Chicago. “They are a really difficult building type for reuse.” The buildings “are definitely at risk,” Moore says. “They’re being closed down or lost consistently, because society has changed, and the purpose for which the buildings were built no longer resonates with as many people as it did.” The most hulking among them are made out of concrete, marble, and steel, Moore explains, so reimagining the interiors is a heavy lift. Still, some have managed to pull it off—Detroit’s sprawling temple, for instance, is now a hopping concert hall and wedding venue.

Other buildings that were once meeting places for fraternal organizations have found a second act, too: New York City Center, a buzzy, lavishly ornate performing arts hub, began its life in 1923 as a Neo-Moorish meeting space for the Shriners, formerly known as the Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine. And in Seattle’s historically black Central District, the Washington Hall performance space, which dates to 1908, was once a gathering place for the Danish Brotherhood—and later for the Sons of Haiti—before a fire swept through and the roof fell into disrepair. Historic Seattle purchased it, reckoned with “decades of deferred maintenance,” including a new roof and an elevator, and reopened it in 2016 after a $9.5 million renovation, says Eugenia Woo, the organization’s director of preservation services. Now, local arts organizations are the building’s tenants. The structure had “really became an anchor to the African-American community, and we didn’t want to change that,” Woo says.

Adaptive reuse is no longer on the table for the Aurora temple. Demolition crews have already begun dismantling the charred building, a process that’s expected to be wrapped in about 50 days and cost somewhere around $780,000, a city spokesperson told the Chicago Sun-Times. As the crew picks through the wreckage, they’ll salvage four columns that once soared above the entrance. A few months from now, those will be all that’s left of the temple.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook