Meet the Woman Preserving the History of Oregon’s Black Loggers

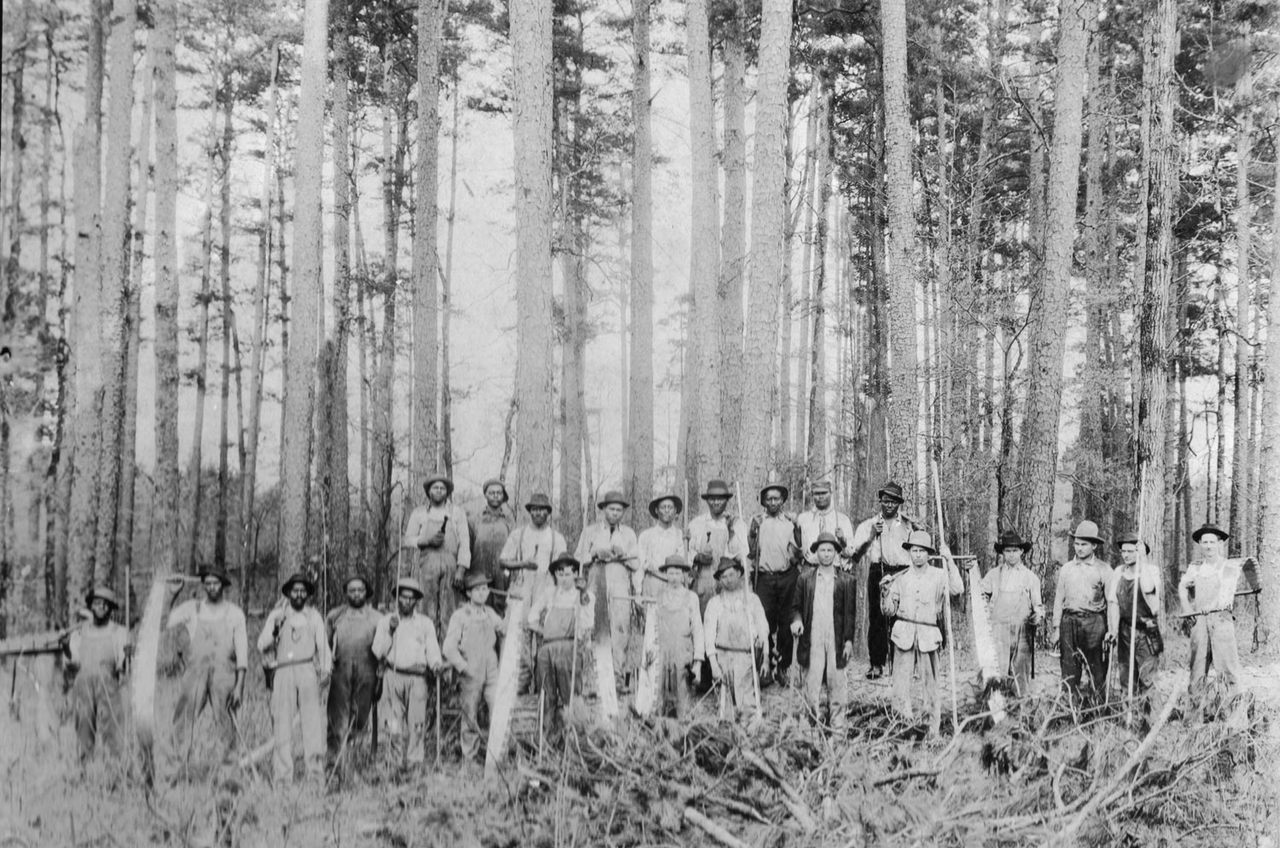

A chance discovery about her father’s past led Gwen Trice to dig deep into the story of Maxville and the families who called it home.

Every summer, Gwen Trice would pack her tent and drive from Seattle, where she lived at the time, to Oregon’s northeast corner, more than 300 miles away. There, in the shadow of the Wallowa Mountains, working ranches and glacial lakes dotted the high desert landscape. The rural setting was not unfamiliar to Trice; she’d grown up in La Grande, just an hour or so to the southwest. But she’d always felt a special connection to Wallowa County. Trice would join others, camping along the Wallowa River and participating in the annual Tamkaliks Celebration, an event organized by the Nez Perce Tribe each July to acknowledge and celebrate its millenia-long presence in the valley. It was during one of these visits that Trice made an unexpected discovery: Her own family also had roots in the Wallowa area.

Intrigued to know more, Trice made her way to Promise, a small community nearby that holds a reunion for residents and their descendents. There she learned that, in the 1920s, her father, Lafayette “Lucky” Trice, had worked as a logger in Maxville, just a few miles from where she stood.

Maxville had been a thriving community of a few hundred people. It was owned by Bowman-Hicks, a Missouri company that, like other lumber companies in the area, recruited skilled loggers from the South, regardless of race. These small company towns were unusually diverse for the state: Oregon’s infamous exclusion laws, which prohibited Blacks from settling in the state, were not generally enforced and were repealed in 1926, but for decades their mere existence discouraged Black families from moving there. Production at Maxville shut down in 1933 after the onset of the Great Depression brought construction to a standstill and the demand for timber plummeted. Today the site is a ghost town: Towering pines surround the last remaining structure, the town’s meeting hall.

For almost 20 years, Trice has committed herself to documenting Maxville and Oregon’s Black logging history, eventually founding the Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center, located about 40 miles from the actual town site. With the recent purchase of 240 acres of land that includes Maxville, the center plans to add additional programs and outdoor tours.

Atlas Obscura spoke with Trice about her Maxville roots and why sharing this story has become her life’s work.

How did you first learn about your family’s connection to Maxville?

It was 2003 and a woman (at the Tamkaliks Celebration) said, “You ought to go up to the Promise Reunion, you know, your people are from that area.” And I thought, why have I never heard that before?

I went to the reunion, which is about seven miles from Maxville. I came up this long, dusty gravel road and pulled in—of course, I was the only Black person in the middle of nowhere in the mountains of Eastern Oregon. For the next six hours or so, I spent time listening to stories of my father.

What was it about these stories that inspired you to found Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center?

I wanted to have the American narrative told with the inclusion of African American people, of black and brown people of color, all of us, with all the perspectives, so it becomes a truer account of our history. And so as the founder of a cultural museum about timber I am able to bring forth the faces of not only Black loggers, but Greek loggers, Filipino, Hawaiian, Japanese, Chinese—there are so many of us and that’s not a complete list. I’ve interviewed Native American logging family members as well. This was in Oregon—not necessarily just Maxville—but it’s Maxville that serves as a template to tell our history. And then it became very clear that this story wasn’t just mine, that it was a story of Oregon’s history that hadn’t been told.

How did you start researching that history?

My father arrived in Maxville in 1923. Most of the people that I needed to interview and talk to were in their mid-to-late 90s. I had to get as many interviews as I possibly could. So I traveled to Texas and other parts of Oregon and California to capture some of these other stories. When I went to the Promise Reunion, the community knew I was coming and they were prepared. They’d put together these mimeograph sheets tied with big orange yarn and said, “Here’s your family’s story.” Kind of like, now you’re the bearer of your family’s history.

What was the Maxville logging community like?

Maxville had approximately 400 people and about 15 percent of them were African American. Maxville was owned by a southern lumber company, so Jim Crow laws were still in place: two baseball teams, two schools. There were a lot of guidelines, and a lot of people didn’t follow those guidelines. One of the local men around here got hit by a dead tree: Dad picked him up, ran with him, and saved his life. And we’re friends with that family still.

How does Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center help preserve Oregon’s logging history?

It’s important to build platforms to tell history, but it’s equally important to bring in people whose history we are supporting; that they tell the history through their perspective. I’m not here to tell Japanese logging history, and that’s why I work with a Japanese museum. It’s the same thing with the Greek loggers. And so we definitely are here to build a platform for all of us and it’s not on me to do that. I don’t want to do to others what’s been done to African American people and other people of color. We all need to tell (our) perspectives and it becomes so much richer. And that’s what the United States has been about.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook