Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the ‘Olympics of Hula’

Hawaiʻi’s Merrie Monarch Festival is arguably the most prestigious event of its kind.

Every spring, thousands of hula fans descend upon the Hawaiian town of Hilo and line the bleacher seats at Edith Kanaka’ole stadium. Thousands more across the islands—those unable to make it to Hilo themselves—watch live broadcasts on their televisions or computer screens. All these people are showing up and tuning in for the beloved Merrie Monarch Festival, sometimes referred to as “the Olympics of hula.” It is arguably the world’s most prestigious (and consistently sold out) hula competition.

The three-day competition is part of several week-long events held throughout Hilo, home of Merrie Monarch since 1963. They include exhibition hula performances, a Hawaiian arts fair, an individual hula competition for the Miss Aloha Hula title, and a royal parade through downtown. In 2019, 23 halau (hula groups) will compete for a panel of seven judges. Upwards of 29 groups have competed in previous years.

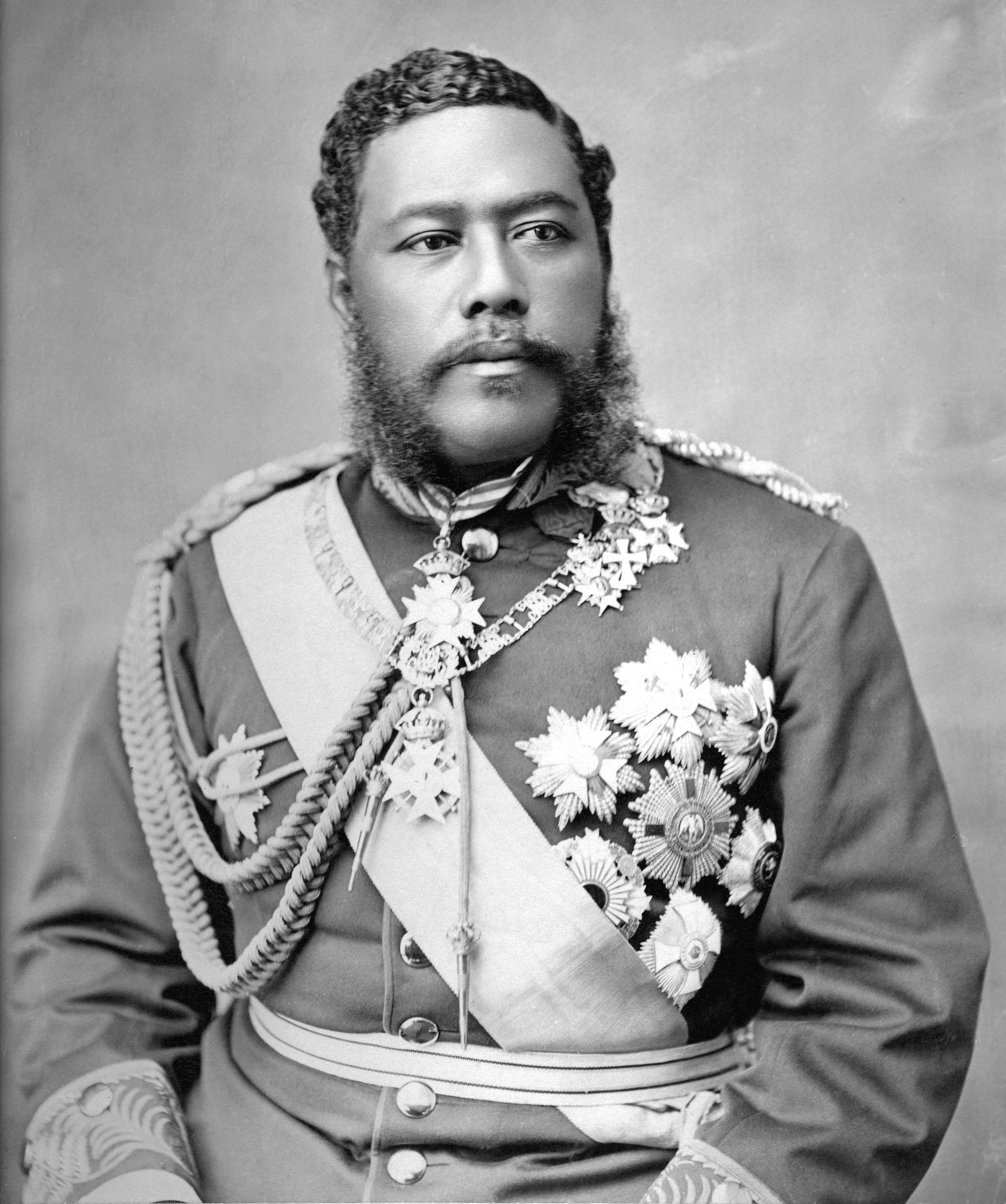

Much credit is given to King Kalākaua, the last of Hawaiʻi’s kings, for reclaiming hula’s place in Hawaiian society. He was elected to the throne in the 1870s by the Hawaiian legislature, and often hosted hula-filled celebrations, including at his coronation. Merrie Monarch was Kalākaua’s endearing nickname and it is his contribution to hula that the competition honors every year.

“It’s electrifying,” says Robert Ke’ano Ka’upu IV, who grew up in Hilo. Ka’upu has participated in the invitation-only competition for the last 30 years as a spectator, dancer, chanter, costumer, and now as kumu hula. In short, a kumu hula, sometimes abbreviated as just kumu, is a hula instructor, but they are also part historian and cultural guide, responsible for passing down Hawaiian traditions to their students from the kumus that came before them. His halau, Hālau Hi’iakaināmakalehua, will return to Merrie Monarch this year. “I don’t get excited like this for any other competition,” he says.

During the festival, every inch of a performance is scrutinized. Dancers are evaluated and earn points for the way they enter and exit the stage, their facial expressions, posture, costume, lei, and adornment, says Ka’upu. However, the bulk of scoring is placed on the kumu’s interpretation of a song, known as a mele, and how well dancers interpret their kumu’s vision of the performance.

To assist in deliberations, every competing group provides judges with a fact sheet that corresponds to each performance. These fact sheets, which are due before the competition, explain everything from a mele’s background to the meaning of the lei that dancers wear “so [the judges] get a better understanding of what each halau is doing,” says Ka’upu. He adds that his halau will submit more than 70 pages of fact sheets to the judging panel for the competition this year. Judges bestow high scores to those who best personify technical excellence, and ultimately the expression of Hawaiian identity through chant and dance.

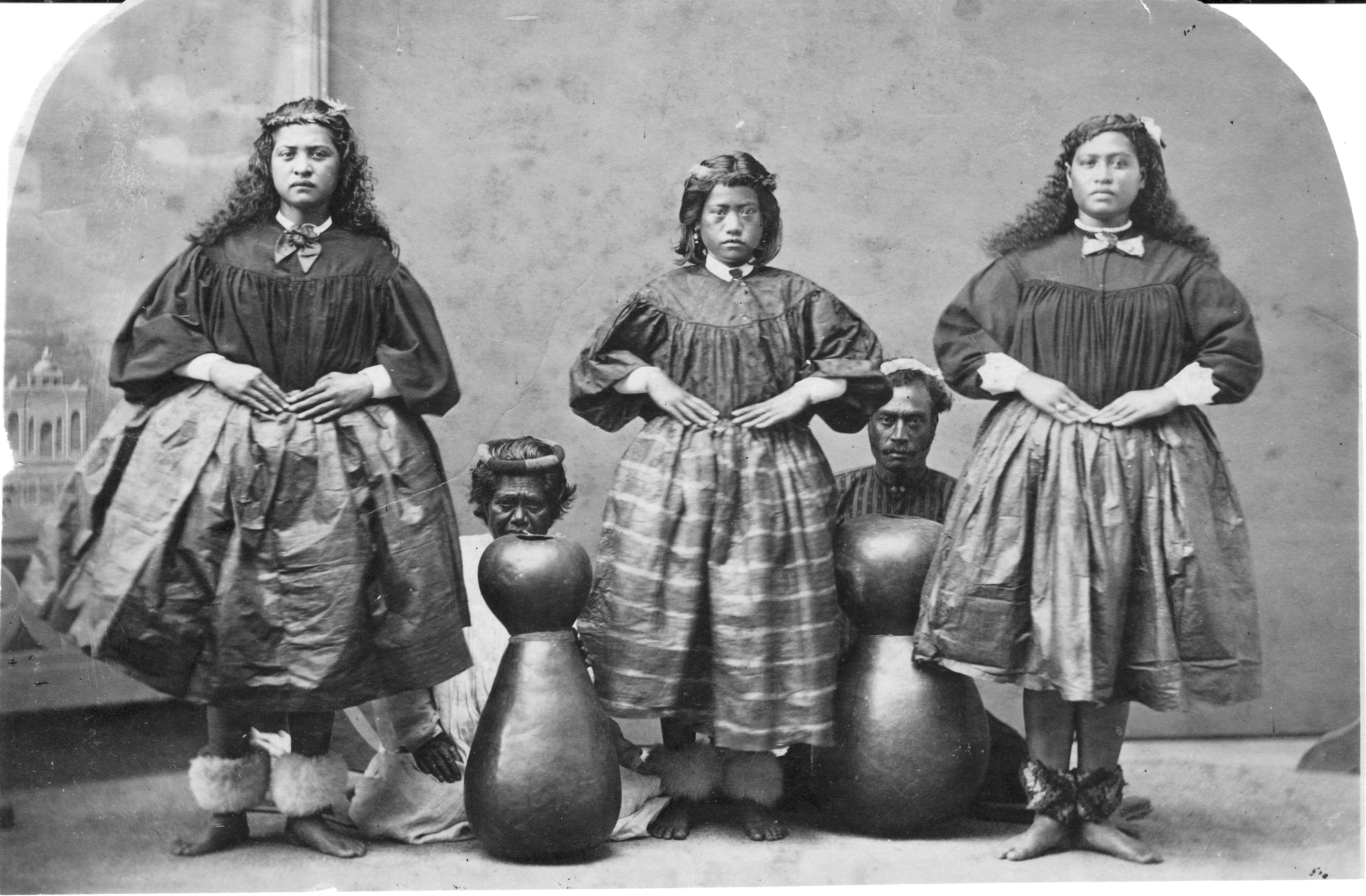

Individual and group performances fall into two categories: hula kahiko and hula ‘auana. Hula kahiko, or ancient hula, is hula before missionaries from New England arrived. Hula ‘auana is its contemporary counterpart and the type of hula visitors to Hawaiʻi typically see at a luau or shopping mall performance. While footwork in ancient and modern hula remains largely consistent, hula kahiko and hula ‘auana—in general—can be parsed by the instruments used and by dancers’ attire, notes Dr. Taupouri Tangarō, director of Hawaiian culture and protocols at University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo, in an email. Dancers competing in the ancient hula category might use ‘Ili ‘ili, pairs of smooth pebbles arranged in each dancer’s hands to create percussive sounds. Alternately, the ‘ukulele commonly accompanies contemporary hula, along with the guitar or piano. The ‘ukulele has remained an inextricable part of Hawaiʻi’s identity since Portuguese immigrants brought it to the islands in the 19th century.

Hawaiian culture existed without the written word until western contact, so Hawaiians passed down knowledge orally and through dance. Through chant and movement, hula narrates place; honors goddesses and gods, such as Pele, goddess of fire; celebrates nature’s surroundings, from birds to waterfalls; and records genealogy and human emotion. “Kaulilua,” for example, is one of Merrie Monarch’s most performed ancient hulas. The mele likens a woman to the island of Kauaʻi’s verdant Mount Waiʻaleʻale.

Hula is a celebrated cultural tradition today, but there was a period—nearly five decades—when hula’s role in Hawaiian culture was suppressed. In 1819, King Kamehameha II let the kapu system, a set of rules and regulations that governed many aspects of Hawaiian life, lapse. In doing so, he created a religious vacuum and ideal conditions for Christianity to take root when American missionaries arrived the following year. As American awareness of hula gained momentum, so did the demonization of hula in the press and public policy. By Christian standards, there was “no place for what was seen as lascivious gyration,” or “the works of the Devil,” notes Tangarō of missionary’s sentiments toward hula.

Much of the monarchy converted to Christianity and this new value system influenced the Hawaiian trajectory, including the decisions of Queen Kaʻahumanu. Kaʻahumanu was King Kamehameha I’s confidant and favorite wife. After Kamehameha’s death, she co-ruled the monarchy with King Kamehameha II. In 1830, a converted Kaʻahumanu issued a ban on public hula performances. According to a paper in The Hawaiian Journal of History, it was likely an attempt to silence “public demonstration of sexuality on the grounds that it was vulgar, savage, and a violation of their Christian morals.”

As Western influence grew and Hawaiʻi’s fate approached annexation and eventual U.S. statehood, so did the need for local manpower to fuel its new sugar economy. In 1858, missionaries with a keen interest in sugar’s profits pursued legislation to suppress hula even further, citing lethargy in sugar cane fields, promiscuity, and attrition from Sunday service. Records show a code of conduct published in 1859 required a license for ticketed, public hula performances. Yet hula persisted under the mesh of legal restrictions and moral shaming. Hawaiians still danced, particularly in more rural areas where government oversight trickled, missionary presence was scarce, and police all the more so. “Hula was never lost,” says Tangarō.

And although the decree requiring licenses was repealed in 1870, opposition to hula continued to play out in the press through the early 20th century. The Hawaiian Gazette, a pro-sugar industry newspaper, ran an editorial in December 1886 condemning hula as, “an immoral dance,” that “cannot claim for itself a poetry of motion or a poetic idea,” and declared, “It is no use Hawaiʻi posing as a Christian State, or even a civilized State, until the stain of the hula is removed.”

That same year, King Kalākaua welcomed public hula performances at his 50th birthday celebration (his Silver Jubilee) on the grounds of ‘Iolani Palace in Honolulu. Several years prior, hula performers were present at his coronation. Before Merrie Monarch added hula competition to its event lineup, the festival’s early years hearkened back to the spirit of Kalākaua’s Silver Jubilee. His frequently cited words—“Hula is the language of the heart, and therefore the heartbeat of the Hawaiian people”—capture the sentiment of a renaissance that revived aspects of Hawaiian culture formerly suppressed, including music, art, medicine, sport, and, of course, hula.

Today, hula is practiced and performed globally, with halaus across the U.S. and abroad. As hula resonates around the world, it endures in Hawaiʻi. “Hula is place, it is its people, it is all that is Hawaiʻi,” says Ka’upu. And as far as hula competition goes, Merrie Monarch remains its benchmark. Come late April 2019, as in years past, proud bare feet will assemble on stage in Hilo, earthy fragrance permeating the air, spectators rapt as the culmination of months and sometimes years of rigorous practice begins and centuries of history come alive.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook