California’s Mexican-American History Is Disappearing Beneath White Paint

It’s surprisingly hard to protect beloved public art.

On July 15, 2019, Maria del Pilar O’Cadiz learned that someone painted over one of her father’s murals—another one, that is. The news came in a text from her sister, who was driving home from work at an elementary school in Santa Ana, California. She had just passed the wall, on Raitt Street, to see it was a shocking white. When Pilar O’Cadiz received the text at work, she screamed. “My coworkers wondered if someone had died,” she says. “And it felt like someone had.”

Before it was whitewashed, the Raitt Street wall held a mural by artist Sergio O’Cadiz, who passed away in 2002. The mural, which was painted in 1994 by both the artist and local children, with the permission of the owners of the land the wall abutted, contained scenes of the old Santa Ana cityscape, with caballeros on horseback and children carrying banners that read “Love,” “Tolerance,” and “Peace,” among other messages. A painted scroll noted, in English and Spanish, that the mural was dedicated to “the children of Santa Ana and the people who work for their future.”

It was, as one can imagine, a beloved landmark for the community, which might explain why it escaped graffiti and tagging for nearly a decade. It was only in recent years that those depredations began to accumulate. There were some thoughts and discussions about restoring the mural to its original condition, but no action had been taken. Then, in July, neighbors spotted a solo artist—no one knows who it was—attempting to restore the mural, without the permission of the property owner or the O’Cadiz family, according to Voice of OC. For reasons that aren’t quite understood, the property owner had the entire mural painted over. “It’s silencing our history and our community’s value,” Pilar O’Cadiz says.

Sergio O’Cadiz Moctezuma was born in Mexico City in 1934. He studied architecture at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. He moved to Orange County around the time that the Chicano Movement, a civil rights effort aimed toward empowering Mexican-Americans and sprinkled with revolutionary themes, began to gain momentum. Perhaps the movement’s most significant and visible expression was in the form of murals. In the 1960s and 1970s, more than 2,000 were painted in Los Angeles alone, the vast majority by Chicanx muralists, according to a timeline from the exhibit ¡Murales Rebeldes! L.A. Chicana/Chicano Murals Under Siege, which documented the city’s disappearing murals (and is on display until the end of 2019). Within this context, O’Cadiz became one of Orange County’s most prolific contributors, according to investigative reporter Gustavo Arellano’s 2012 cover story on O’Cadiz for OC Weekly.

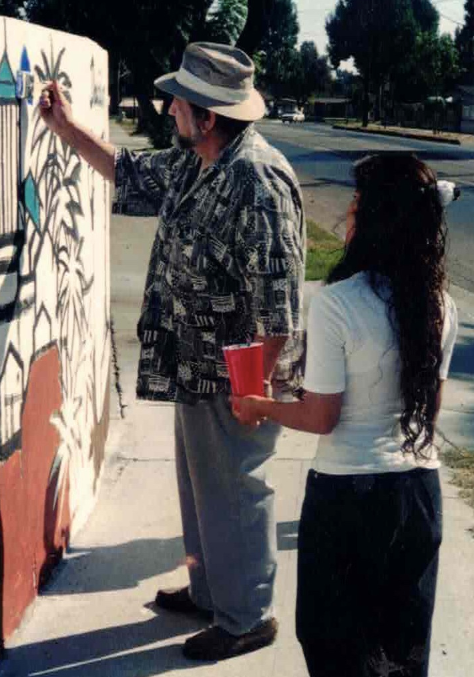

O’Cadiz’s oeuvre consisted of more than murals, but he became known for them. “From the moment a public artwork is made and exists in public space, it impacts the lives of everyone who passes by it,” says Janet Owen Driggs, director of the Cypress College Art Gallery, who is curating an upcoming retrospective of O’Cadiz’s work. “The people who painted it feel their sense of pride and accomplishment, and they see their faces reflected.” Though Pilar O’Cadiz was not present for the painting of the Raitt Street mural, she assisted her father in several other projects. “The key to his artistic process was to get the community involved,” she says. “He listened to them, and he got their input.” In the 1982, inspired by her father’s work, Pilar O’Cadiz painted a mural of her own, in the Third World House dormitory at Oberlin College. “My college flew my dad out and as soon as he saw it, he said ‘Good try, Pilar,’ and went over the whole thing to fix it,” she says. “And it came out gorgeous.”

In the 1970s in Southern California, O’Cadiz’s community murals appeared throughout Orange County. He designed murals inspired by the Chicano Movement for Santa Ana College in 1974 and the Fullerton Public Library in 1974, and in 1976, his magnum opus: the Fountain Valley Mural on the Calle Zaragoza wall of Colonia Juarez, a Mexican-American neighborhood in Fountain Valley.

This 600-foot-plus wall depicted 25 scenes from the community’s history and heritage, including the first arrival of Mexican peasants in California and the Mexican army’s victory over France at the Battle of Puebla in 1862. One scene stood out as particularly controversial, depicting cops clad in gas masks dragging a Chicanx youth toward a police car. The mural was completed four years after Mexican-American activist and journalist Ruben Salazar was killed by a stray tear gas canister fired by a Los Angeles County sheriff.

The police scene was eventually defaced with white paint, which O’Cadiz did not retouch. “The idea of [a] mural is compatible with the American concept of democracy and freedom of expression,” he wrote in response to the defacement, according to materials published in conjunction with ¡Murales Rebeldes!. “Being an American is having the freedom to be as Mexican as I want.”Though the city withdrew funding and support for the mural, O’Cadiz and volunteers finished it anyway. Over the years, the city refused to allow O’Cadiz to restore the mural, so it fell into the kind of disrepair that, by 2001, made it easy for officials to bulldoze the entire thing.

As public art, murals are usually aren’t endangered by direct opposition or censorship, according to the curators of ¡Murales Rebeldes!. More often, they fall victim to prolonged neglect and the tricky bureaucracy of their maintenance and preservation, says curator Erin Curtis.

That was the fate of much of O’Cadiz’s public art. A fountain he constructed in Fountain Valley was turned into planters, and half of his mural on City Hall was demolished for the construction of an annex. Later in life, he contemplated suing the cities that destroyed his work, but never took action.

Pilar O’Cadiz, education director of an engineering research center at the University of California, Los Angeles, has taken up the cause of preserving her father’s surviving work. Before the Raitt Street mural was whitewashed, she had started working on its restoration—a case she’s still building.

Complicating the already complex reality of preserving public murals, the Raitt Street wall is on private property, and the landowner does not live in Santa Ana. There is, she says, a state statute protecting public artwork that requires private property owners to notify the artist’s next of kin before removing or altering the work. “But that’s a battle that I don’t think would resolve in our favor,” she says. “I want to make a friendly plea. Like, ‘This is the artist. This is the significance to the community. This is the historical heritage.’” If these efforts fail, she plans to explore recreating the mural in another part of the community.

At Cypress College Art Gallery, the exhibit J. Sergio O’Cadiz Moctezuma: El Artist, curated by Driggs, opens September 19 and will run through November 14, 2019. Pilar O’Cadiz hopes that the buzz might benefit her cause at Raitt Street. Driggs sees a special kind of value in the artist’s local work, as opposed to his larger, more ambitious commissions. “Sergio’s work in his community murals speaks to a different way of being in the world than the way that best supports the status quo,” she says. “A sense of community, lack of hierarchy, about celebration and sharing, and speaking the truth of the community.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook