Mexico City’s New Day of the Dead Parade is Based on a James Bond Film

The cultural event first appeared in “Spectre.”

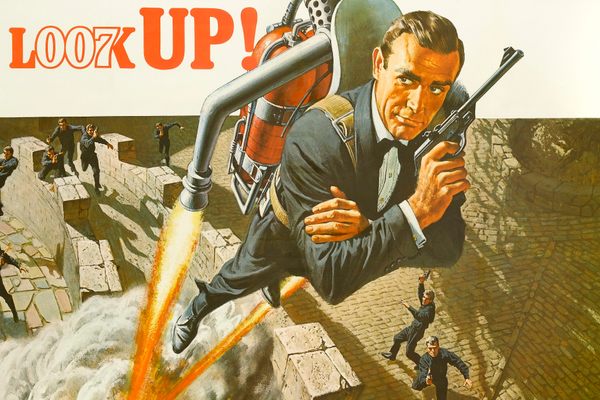

Mexico’s famous Day of the Dead traditions might change because of eight minutes of Hollywood film. In a pre-credit sequence in Spectre, Sam Mendes’ second Bond film as director, and Daniel Craig’s last as the title character, 007 thwarts a terrorist plot in during a Day of the Dead parade in downtown Mexico City, chasing the Italian bad guys around giant skeleton floats, and through a crowd of thousands of revelers wearing elaborate costumes. The sequence features stunning shots of Mexico City landmarks, including the Zócalo, the city’s main square, and the Torre Latinoamericana, a towering 1950s skyscraper.

Mexico City fought hard for its eight minutes in Spectre. Leaked documents show that Mexican officials offered Sony Pictures millions of dollars in tax incentives in exchange for featuring the capital city in the Bond film. Sony Pictures even let Mexican authorities make certain changes to the script, including featuring a major Mexican actress, Stephanie Sigman, as the “Bond girl” and making the villains another nationality than Mexican.

There was only one problem: the tradition depicted in the movie was completely made up. There are many traditions across Mexico that are associated with Day of the Dead, but a parade through downtown Mexico City has never been one of them.

Bringing Bond to Mexico City was part of a project to promote the capital as a major tourism destination. Tourism is one of Mexico’s main sources of income, earning hundreds of billions of dollars a year, and even surpassing oil revenue in the first part of 2016. Mexican chambers of commerce speak of a “Season of the Dead,” running from October 29 to November 2, as an important tourism season, bringing much-needed income to certain rural areas.

Large parts of Mexico City’s historic downtown had to be shut down to accommodate the filming, which took place over 10 days in March of 2015. The street closures cost 6,500 local businesses over 60 percent of their revenue, totaling at least 376 million pesos (about $20 million) in losses.

Mexico City Tourism Secretary Miguel Torruco Marqués, who was involved in securing the film deal, saw the movie as (expensive) advertising for tourism to Mexico. He assured angry business owners and motorists that the traffic problems and lost revenue would be more than made up for when Mexico City became a “Bond City.”

“Bond Cities start booming as soon as the movie comes out,” Torruco Marqués told reporters at a press conference on April 1, 2015. “Not only in tourism, but also in investment. There will be a huge economic boom, and it will make up for the inconveniences.”

However, Mexico’s tourism authorities began to worry that tourists who have seen Spectre might come to Mexico City expecting a parade like the one they saw in the movie, and be disappointed to find that it doesn’t exist. In order to take advantage of all the exposure they had gained from Spectre, they would need to invent a new tradition.

So, on Oct. 29, 2016, Mexico City hosted its first-ever Day of the Dead parade. With over a thousand participants, including professional dancers, choreographers and visual artists, and dozens of floats and giant sculptures for the first edition, the parade aims to attract hundreds of thousands of visitors to Mexico City in the future. Torruco Marqués said that it could even compete with the Rio de Janeiro Carnival for the title of the world’s biggest parade.

The event was presented as a showcase of diverse Day of the Dead traditions and art from around Mexico. It also got some more use out of the costumes and props from Spectre.

Tourism authorities made no attempt to hide the fact that the parade was based on the James Bond movie—they referred to it as a “Spectre-style parade” in press communications (but they took out the parts with the collapsing buildings and helicopter tricks).

The artists who worked with the parade created modern dialogues with Mexican rituals surrounding death. Part of the parade was devoted to the tradition of la Muerte Niña, the mostly-defunct practice of creating family portraits—first oil paintings, later photographs—with recently-deceased children dressed up in extravagant clothing, sometimes as angels with heavenly crowns.

At the 2016 parade, a retro-modern reimagining of la Muerte Niña appeared as adult women seated in meticulously preserved classic cars filling in for cradles, wearing festive colors and holding balloons.

From a tourism standpoint, the event was a success: attendance was higher than anyone expected, and attracted many foreign visitors. City government estimates say that 425,000 people lined the streets running from the Angel of Independence to the Zócalo. Few other events could have brought so many people out in Mexico City—not a protest march, not even a free Roger Waters concert.

It’s too soon to say how much tourism income the parade brought to Mexico City, but a forecast by a chamber of commerce estimated about a billion pesos (about $50 million) in income for Mexico City businesses related to the parade and the Formula 1 Grand Prix, which took place the same weekend.

However, many Mexicans are offended by the government’s enthusiastic support for an invented ritual based on a Hollywood movie. Magaly Alcantara Franco, a student at the National School of History and Anthropology, believes the parade was influenced more by potential tourists’ perceptions of Mexico than by Mexican traditions themselves.

“For me, what I saw that Saturday didn’t represent, not even minimally, what the Day of the Dead celebrations are,” she says. “It was based on an idea that isn’t even Mexican, an idea that was imported from Hollywood.”

Claudio Lomnitz, a professor of Mexican studies at Columbia University, wrote an editorial for La Jornada criticizing the parade. “There’s an element of what we could call ‘national-narcissism,’ of a national imaginary in love with its own image, reflected in the mirror of Hollywood,” Lomnitz writes.

This isn’t the first time that rituals surrounding death have been manipulated by the Mexican state for political purposes. As Lomnitz shows in his book Death and the Idea of Mexico, the late-fall death festival was born out of an effort by the Catholic Church to accommodate indigenous death customs with All Souls’ Day and All Saints’ Day. Later, efforts by the revolutionary state to build national identity led to the holiday’s current form and level of popularity.

For Lomnitz, what’s different about the new parade is that it is only a representation or performance of the Day of the Dead—the parade represents an image of Mexican culture, composed with the views of foreigners in mind.

Due to the success of the first incarnation of Mexico City’s Day of the Dead parade, it will probably become a yearly tradition. The event is essentially a Day of the Dead digest, a show, rather than a participatory tradition. But for a short-term visitor who wants to see Mexican death culture, it might be exactly what you’re looking for.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook