War, Romance, and Everyday Life in Beirut’s Emerging Alt-Comix Scene

A generation of creators is carrying on the Arab world’s history of expression and frustration.

Joseph Kai wears a scraggly beard, a black mock turtleneck, and tortoiseshell glasses, and is eating smoked salmon on a bed of greens in a Beirut café. He has just returned home from the French hillside village of Angoulême, which hosts the International Comics Festival, Europe’s premier gathering of comic artists and graphic novelists. Kai and his colleagues who publish the zine Samandal were only the second non-European winners of the festival’s prize for alternative comics, a banner moment for the Lebanese cult publication. “It was the first time we felt that we’re part of a big community, part of a movement,” he says. “It was a new feeling.”

Alternative comics or alt-comix are graphic narratives for adults that encompass fiction and nonfiction, the gritty and the intimate, stories far beyond superheroes, with a diverse range of influences, from literature to reportage to pulp. They’re auteur-driven, often deeply personal, and not professionally produced. Alt-comix were once an underground phenomenon in Europe and the United States, but today many of their most prominent authors have graduated to become mainstream provocateurs, who hit the bestseller lists and spark debates on the evening news. Graphic publications in Lebanon, though, remain a novelty. But they are not new. A little-known history connects Samandal and these Lebanese artists and creators with their spiritual forebears who, a generation prior, used comics to document the fallout of the Lebanese Civil War in the 1970s and 1980s.

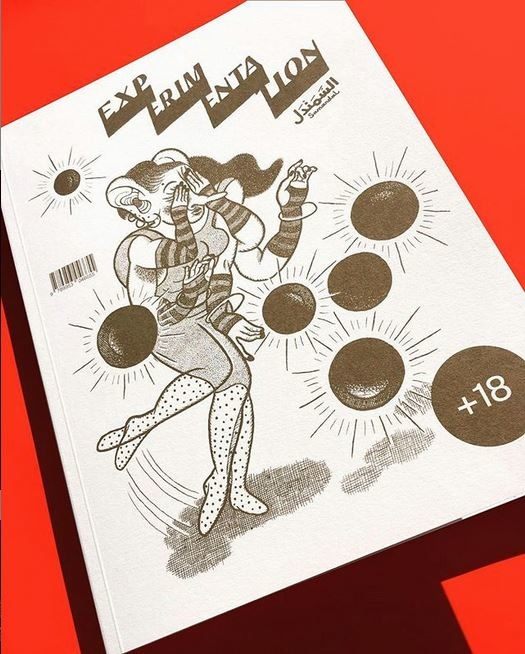

Samandal, technically, is a comic collective that publishes an eclectic zine in various shapes and sizes, and has incubated a new movement of young Lebanese artists and graphic talent. (The prize-winning issue was its twentieth full-length edition.) An underground favorite of those who haunt Beirut’s cafes, bookstores, and galleries, Samandal the zine is a fattoush of memoir, romance, adventure, fantasy, and the surreal, depending on the whims of each edition’s editor-artist, who choses the theme and constraints. Though the comics are decidedly adult, Samandal is often mis-shelved with children’s books, in part because there’s no other place to put it in Lebanese bookstores.

“The scene is developing,” Kai, 30, says. Tonight he and friends will receive another award, the Comics Guardian Prize from the American University of Beirut’s Arab Comics Initiative. With two accolades, Samandal’s international profile is growing in parallel to other comic-art collectives in Arab capitals.

While alt-comix are a new phenomenon—Samandal was founded in 2007—as a political mode of expression, cartooning has been widely used for over a century in Lebanon and across the Middle East. Samandal is, in a sense, an evolution of this, “the display window for what’s happening,” Kai says. Since the 2011 revolutions of the Arab Spring, the spread of underground comics has accelerated across the region, which has seen a fluorescence of similar scenes in Algiers, Amman, Baghdad, Cairo, Casablanca, and Tunis, taking on topics as varied as migration, war, love, and addiction to social media.

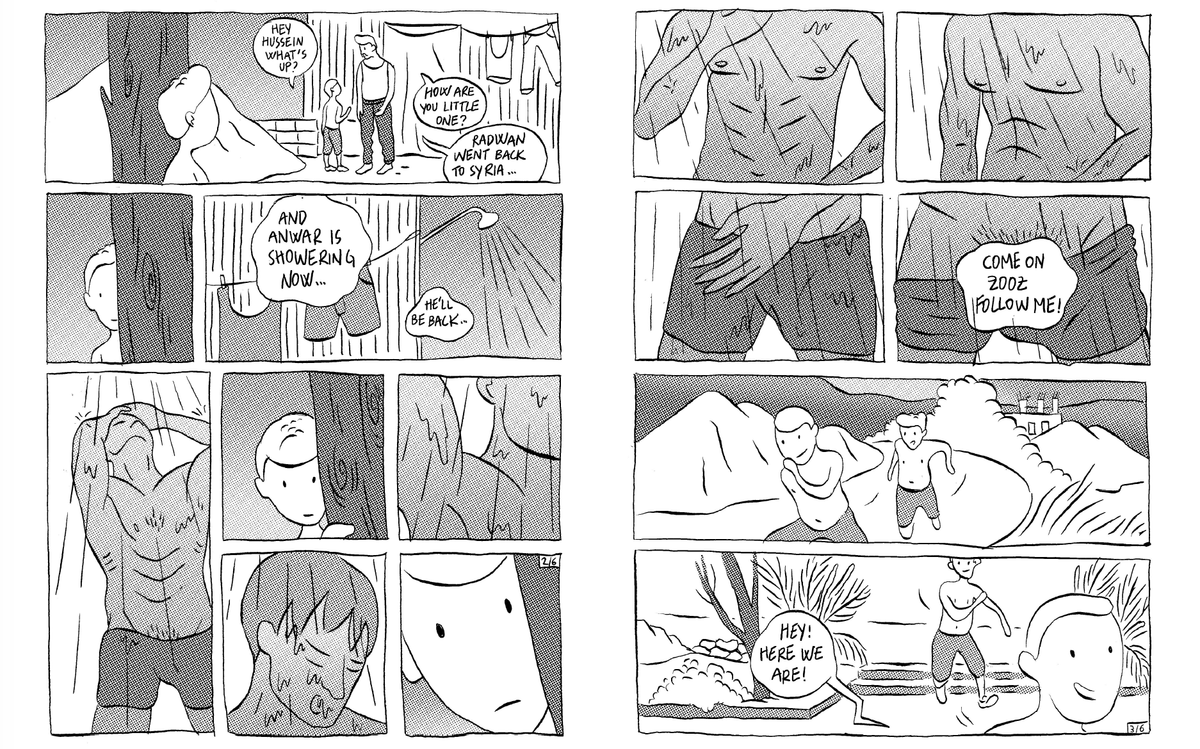

In 2019, as the promise of 2011 has curdled, the Syrian war rages on, and millions have become refugees, Arab comic artists like Kai and others are considering their place. Do they have a responsibility to address conflict and crisis, to grapple with war at a local level? For those in Beirut, the question is unavoidable, as the peaceful city has become an enduring hub of displacement, from the historic refugeedom of Palestinians to the new waves from Syria and, increasingly, other Arab states.

For some Arab and Lebanese comic artists, these crises are urgent and irresistible. But creating and consuming graphic art can also be an escape, a declaration of new priorities that extend beyond the global reputation of the Middle East as a place of civil wars, religious conflicts, and terrorism. “Others might want to shift their attention to something else,” Kai says. “This is another way of claiming their life, this is how they can exist.”

Samandal, which means “salamander” in Arabic, publishes in three languages, uses creative translation techniques, and solicits work from comics artists all over the world. Though their outward image is avant-garde—a highbrow art journal that alternates between automatic drawing and grotesque visual humor—the collective also conducts public education. It is, in many ways, a product of its time and place. Artists from the crew lead workshops for refugees in Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley, where many Syrians have landed. Samandal also brings comics into public school classrooms, and recently worked with the anti-poverty group Oxfam to publish a comic featuring the stories of women called هُنَّ, or Huna (the feminine form of “they”).

“We are aware of our responsibility to give tools to people who want to write about these issues,” says Kai. “That is why we intervene in refugee camps.”

Kai was recruited to draw for the zine in 2010, while he was pursuing a masters in illustration and comics at the Lebanese Academy of Fine Arts. Francophone comics, or bandes dessinées, are popular on Beirut newsstands, and Kai grew up with the adventures of Tin Tin and Asterix. As a student, he found the work of inventive comic artist (and jazz trumpeter) Mazen Kerbaj, in particular his dreamy, rough-hewn 2004 chapbook 24 poemes. After years of studying fine art, Kai saw something authentic and interesting in Kerbaj’s work: “black and white, totally free, totally improvised. Nothing looked real or conventional.”

During the summer 2006 war between Lebanon and Israel, Kerbaj maintained a visual blog, a rough, visceral sketchbook of 33 days under siege. In self-deprecating self-portraits, he conveyed the quotidian aspects of living amid air raids, including an illustrated backpack survival kit, in case you get stuck at a friend’s house:

my life in a bag

each time i leave my flat, i take with me:

my passport and evan’s one

a mini-disc recorder + microphone

2 t-shirts

2 underwear

2 pairs of socks

a notebook and pens

my trumpet

binoculars

a book

tobacco

a small camera

a lighter

a usb key

a toothbrush

4 batteries

“I wanted to draw like this,” Kai says.

Fun fact: Kerbaj is ambidextrous and can draw with both hands at the same time. he is also downright prolific, with books upon books of strips. Anexhibition, co-created with his mother, Laure Ghorayeb, a poet and artist, is called Laure et Mazen: Correspondance(s), was recently on view at the Sursock Museum, a recently reopened modern art palace. There, his frenetic output wraps around the rooms like a scroll of slapdash lines and jokey speech bubbles in three languages.

Kerbaj began publishing comics in the late 1990s and early 2000s, so he connects Samandal to an older history of Lebanese comics—both underground and in the public eye. Lebanon has had political cartoons since the turn of the 20th century. Comic books for kids grew popular in the 1950s and 1960s. Cairo was the source of beautifully colored, action-packed children’s comics, from local titles such as Samir and Sindibad to Arabic translations of Mickey Mouse, Superman, and Little Lulu comics. A cohort of artists left Egypt in the 1950s as the military took control of the state. When president Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalized the press after the 1967 war, the space for free speech in Egyptian media further contracted, after which Beirut emerged as a new capital of commercial Arab comics for children. At one point more than 35 comic magazines graced its newsstands.

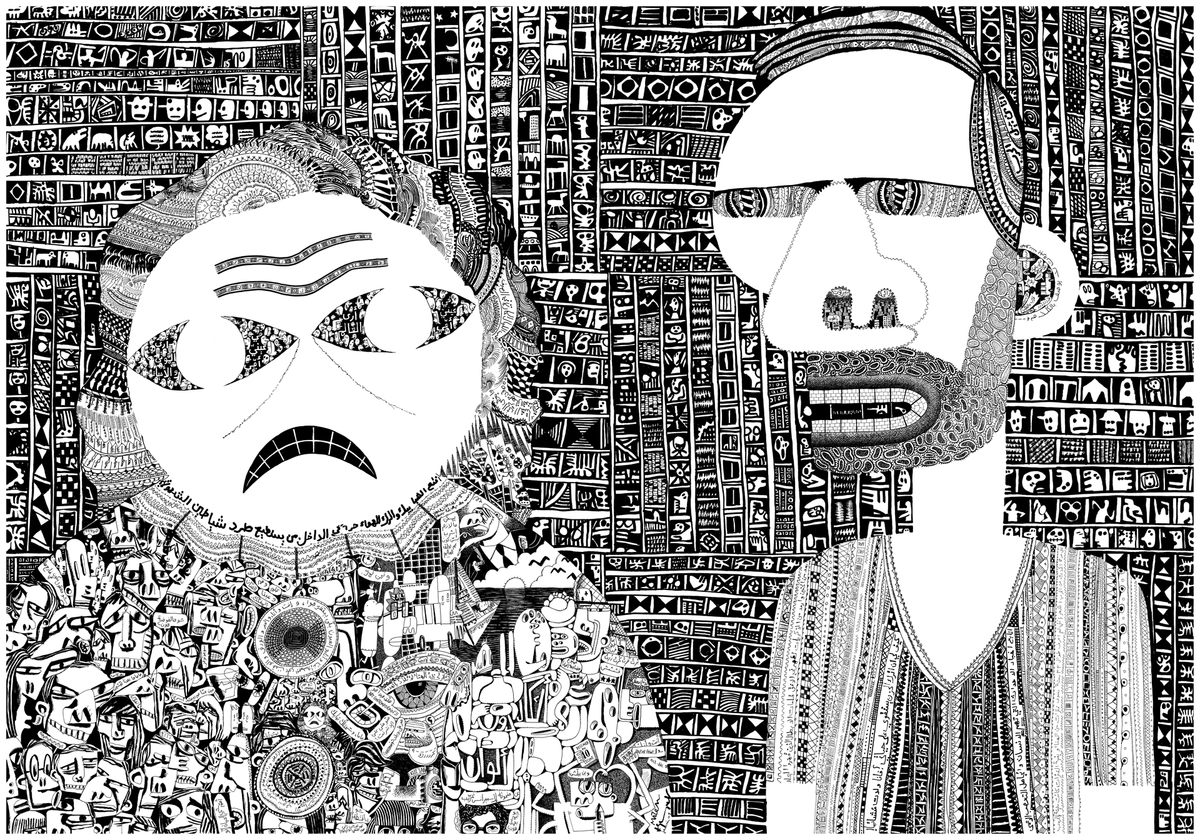

But it wasn’t just popular comics that Kerbaj and Samandal built upon, but another, less-known tradition that documented how the civil war of the 1980s ravaged lives through panels and bubbles. They were explicit. They were graphic. They were for adults.

In 1981, as Israeli planes bombed the Lebanese capital and warring militias enforced curfews and checkpoints, JAD Workshop produced dark comic reflections of the war. Three decades before Samandal would be mis-shelved or not shelved at all, JAD Workshop also couldn’t find couldn’t find bookstores to distribute their dark, oversized comics and graphic novels.

One of the founding artists of JAD Workshop is Lina Ghaibeh, who, as the inaugural director of the Arabic Comics Initiative at American University in Beirut, is today responsible for elevating the study and practice of graphic narrative in the Middle East. In 2015, with funding from a wealthy Lebanese businessman who had once dabbled in cartooning, Ghaibeh established the first archive in the Arab world dedicated to early examples of caricature and cartooning from the 19th century, and the various spheres of underground cartooning they evolved into.

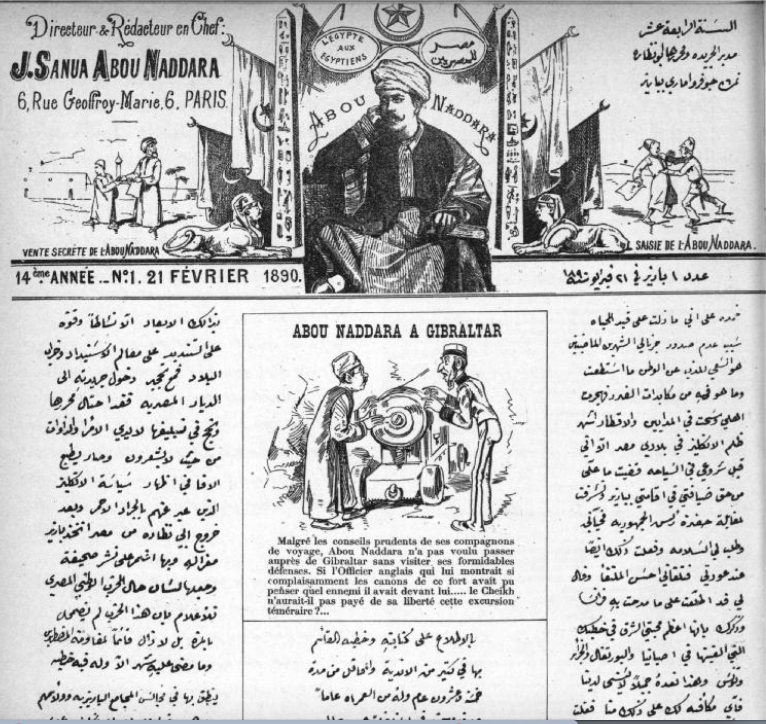

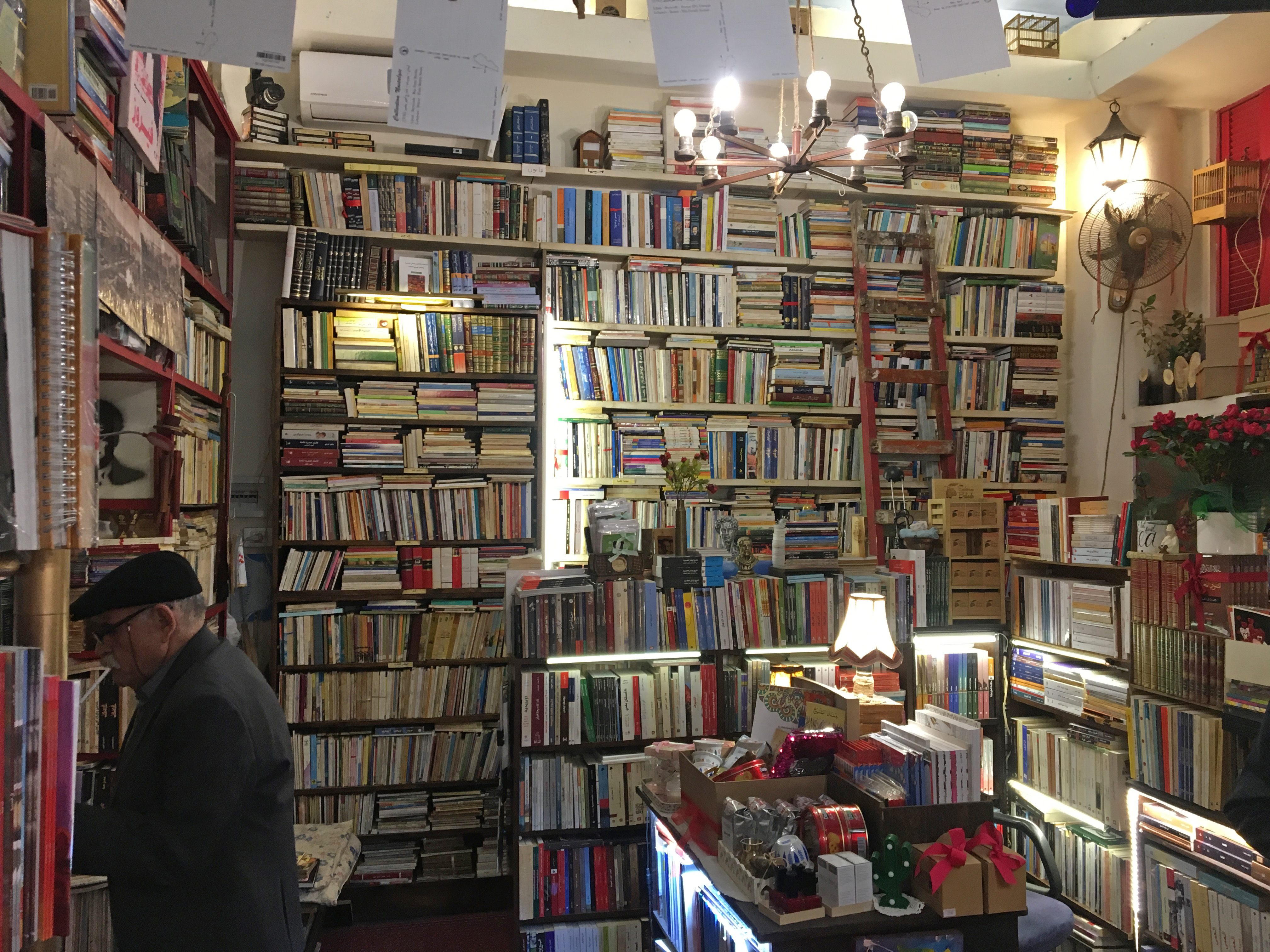

That archive, in a basement corner of the university’s modernist library, includes the early satirical broadsheets by Yaqub Sanu in Egypt, as well as the first children’s periodicals, which initially appeared in black and white. Ghaibeh, whose scholarly post is in the School of Architecture, is captivated by the design and layout of the early generation of children’s comics, as much as by the language, content, and singular aesthetic styles.

What many of these cartoonists from the earliest generation have in common is that they themselves were displaced. Sanu fled Egypt for France in 1878, many children’s comics authors left Nasser’s Egypt for Beirut, and later under Sadat a group of leftist cartoonists fled as well. Some landed in Lebanon and others in the emerging Gulf states. In the archive, there are also monographs of prominent Arab political cartoonists, such as Naji Al-Ali, the Palestinian critic who was gunned down in 1987 in London; and Ali Ferzat, a Syrian cartoonist who survived an attack by Assad’s thugs in 2011 and now lives in exile. On the shelves are also the latest zines from collectives in Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, and more, which Ghaibeh has collected while traveling to comic festivals across the Mediterranean.

With silver hair and knee-high Doc Martens, Ghaibeh is the hip doyenne of the Lebanese comics scene. She calls comics a “critical tool” and, in her drawing and curating, has prioritized “documentation and representation of displacement.”

She has collaborated with her husband, George Khoury Jad, since the early 1980s, when he established the JAD Workshop and published the first graphic novels in the region, including a biocomic called Freud and a surreal nightmare-scape called Carnival, all of which are out of print. Jad exhibited at Angoulême in the 1980s and met the notorious Charlie Hebdo cartoonists Cabu and Wolinski, who were killed along with their colleagues in the 2015 attack on their Paris offices.

“If you want to start a movement of comics for adults, start local,” Jad says, wearing his signature black baseball cap, with his gray ponytail hanging out the back. “And don’t be pretentious.”

The Arab Comics Initiative’s fourth annual symposium of artists and scholars took place in the spring. (Note: The author was an invited speaker, and serves on the editorial board of the university’s new book series on Arab comics.) In a large lecture hall along the gusty Mediterranean coast, Jad delivered a moving talk about early-20th-century exodus stories in American, European, and Arab comics. He noted the trend of reportage and nonfiction portraits of contemporary, failed states, historical conflicts, and postcolonial migrations. Some were made by graphic journalists who visited refugee camps, squats, and border crossings; others by those who spent extended periods of time with survivors of conflict to create illustrated oral histories. These comics largely come from European or U.S. traditions of adult comics, and build upon a similar ethos of documentation through art. There are stories from Smyrna and Alexandria and Algiers and Armenia, written in a cacophony of languages, with a fine sense of detail and expressing great universalities, such as humor in the face of unthinkable conflict.

“From refugee camps in Syria, Turkey, Lebanon, [to] the unwelcome immigrants camps in Europe, artists volunteer to go witness, defend, and collect stories of people with names, coming from villages and cities that have names, running away from torturers who have names, waiting for an unknown future,” Jad told the crowd of students, professors, and artists. He was unable to hold back tears. “Through these artists, [their] names … won’t be forgotten.”

The next night, the night of the conference’s award ceremony, artist and students squeezed between oversized panels from comics about exile, deportation, and identity. The remodeled building where the gathering took place had, during the country’s civil war, been the fault line between East and West Beirut. Today it is, by design, still pockmarked with old bullet holes and studded with rubble—a stark, aestheticized reminder. Kai and I, on the lookout for Ghaibeh and Jad, ambled up six flights of stairs to where snipers had targeted passersby. From the windows of what is now a gallery, we could see Syrian refugee children below, weaving between cars on the streets to ask for money. The exhibition in the gallery, In-Transit, curated by Ghaibeh, includes the work of 37 artists, around 30 of whom mingle around, awkwardly holding champagne flutes. A group of undergraduate students walked in as local news crews filmed Beiruti society mingling with scruffy cartoonists, hipster artists, introverted graphic designers, and jovial children’s book authors. A Syrian ducked so as to avoid a video camera. Discussions could be heard flipping between English, French, and Arabic, with Algerian, Egyptian, Jordanian, Syrian, and Tunisian dialects in the air.

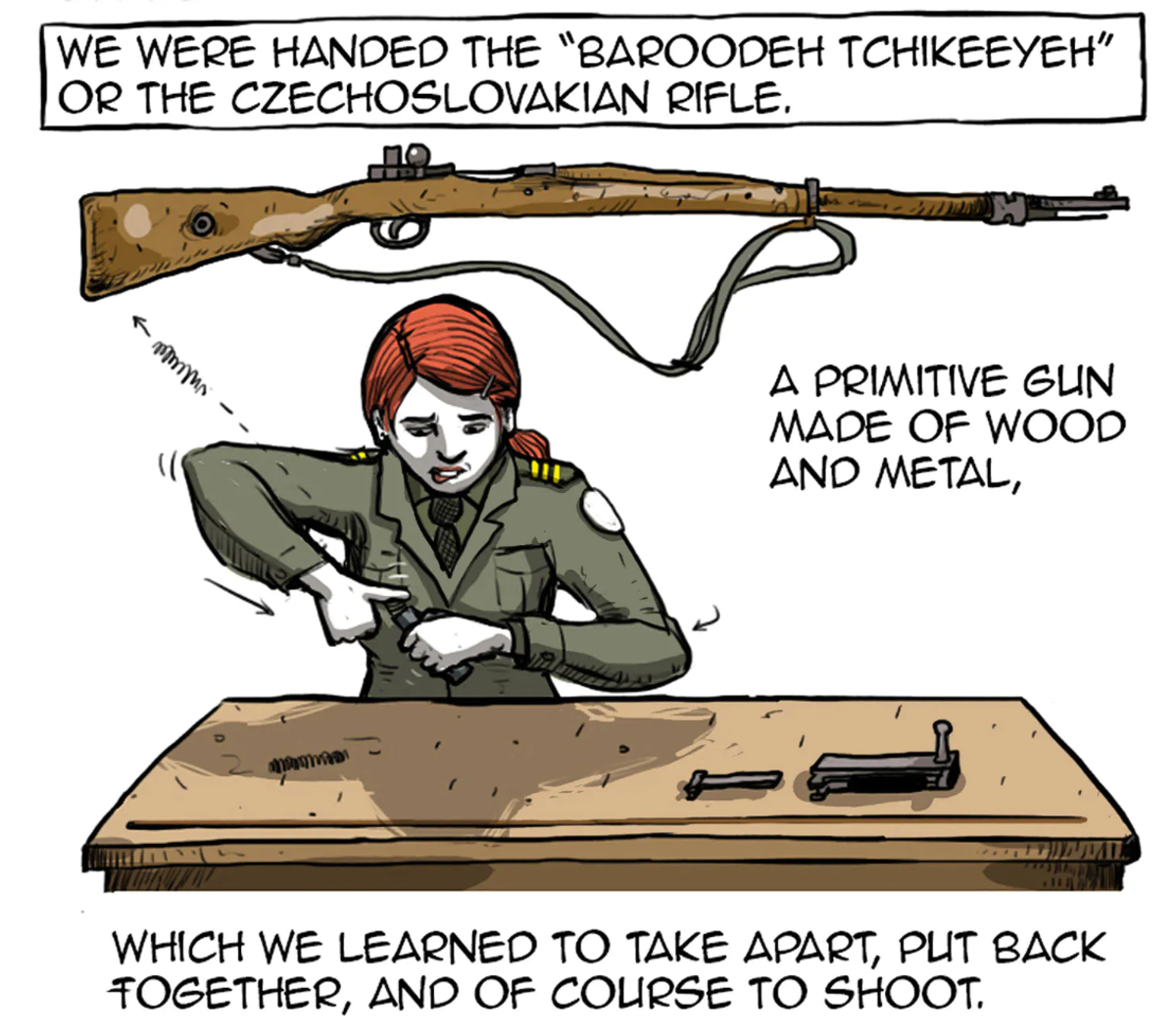

Samandal artists had work on display, including Barrack Rima (a chart of statistics about the refugee crises) and Nour Hifaoui Fakhouri (an intimate take on being Palestinian in Lebanon). There was also the work of Western artists, such as the cityscapes of Raqqa by New York–based artist and journalist Molly Crabapple, who delivered the show’s introductory remarks after arriving on a red-eye. Documentation via illustration, she said, can “make the oppressors unhappy.” Crabapple coauthored, with Syrian reporter Marwan Hisham, a 2018 graphic memoir, Brothers of the Gun, about his escape and return to ISIS-occupied Raqqa. Refugees’ stories are often flattened by outsiders, she said, paraphrasing Hannah Arendt, and she called upon refugees to tell their own stories.

Among the framed works and origami-like boards of comic panels sit two pages of Jad’s new comic, Aleppo Bataclan, his first long-form work in decades. It’s a narrative of inky terror that alternates between a woman whose partner was killed in the 2015 Paris terror attacks and a boy whose father died in a concurrent strike in Aleppo, Syria.

What is an Arab alt-comic, if such a thing exists? Is it stories rooted in language or geography, or is it driven by aesthetics or themes? Ghaibeh emphasizes “the diversity of language of comics out there.” In the pages of Samandal, the common thread appears to be a taste for the uncommon.

Asked about Lebanese comics, for example, Sandra Ghosn, a Paris-based artist originally from Lebanon, says, “I feel there is no such thing.” She drew the cover of Samandal’s award-winning issue, a depiction of a woman-animal hybrid with strange limbs, like a furry cousin of Ed Roth’s Rat Fink. The artist, not the monster, wears a denim jacket, John Lennon glasses, and red lipstick, with a flash of gray in her tied-back hair. “I don’t believe in borders and nations. I feel it is outdated. I don’t think I am inspired by a specific nation,” she says. “Maybe I don’t have enough distance.”

“We are still talking about a very, very small scene,” Kai explains. “It’s super-difficult for me to think of one aspect that is Lebanese…. It has very, very different and various references, and inspirations.”

The reputation of alt-comics in the Arab world today, if they can be said to have one, is leftist, liberal, activist, and progressive, though Samandal is so wide-ranging that it’s hard to see that directly reflected in the collective’s work. Kai, for example, is more interested in form than politics, and doesn’t do reportage.

Last year, he moved to Paris to take up an artist residency at Cité internationale des arts. His graphic narratives unveil personal stories of coming of age and gender and sex. “In France, I feel it might be boring even,” he says, explaining that queer comics get a very different reception there than in Lebanon, where they’re still considered highly subversive. “It’s not something new [there]. I’m just trying to put together my way of representing it. Working on the individual [character] … his body, his dreams, how he moves. Somehow it’s also a study of the queer individual.”

In other cases, national identity is in the foreground, especially as it relates to migration. “I was raised in a family where I had to hide my identity,” says Fakhouri, who is Palestinian and grew up in Beirut. “None of my friends knew I was Palestinian till I was a much later age,” she says. Individuality and the boundaries that nationality places between people—even or especially when they share the same space—figure prominently in her work.

Fakhouri, for one, is concerned that an emphasis on politics would take some of the energy and diversity out of the community. “It’s really important to keep this place for everyone, because there is a lot of violence, suffocation in a way,” she says. “So I think it’s important for artists who want to tell stories to have a platform that offers them a kind of freedom.”

That’s not to say that there aren’t some things in common among Arab or Lebanese comic artists. After further reflection, Ghosn says, “War. War is common. The memory of war, more precisely. I was born in the war; everything I do goes back to this phase that I blocked out completely.”

She recalls the 2006 Israeli invasion as a “mentally intrusive” experience that pushed her to leave Beirut for Paris. “I was really petrified, paralyzed,” she says. “I can’t stay in this country. I couldn’t draw. I had to leave in order to survive mentally. I felt there was a ceiling put on the sky. A closure. The bombs.” Art, illustration, and comics provided a place to reinterpret and recompose those memories.

But pushing those limits in the tradition of alt-comics means that offense, controversy, even danger are possibilities. Censorship has been perhaps the most visible marker of how Arab alt-comix are seen by the outside world, since many of the governments of the region don’t take kindly to criticism of any sort. And any discussion of offense and criticism must mention 2009, when the Catholic Church sued Samandal and the collective was compelled to pay $20,000 for caricaturing Jesus on the cross. It’s not an alarming judgement compared to more violent acts of censorship across the region, but such actions against creators aren’t uncommon, and certainly impact freedom of expression. In addition, the optics are peculiar: the might of the Catholic Church looming over the ragtag collective of artists. But that most public experience is not what this scene wants to be defined by.

“At some point, we need to move on,” and create satisfying works of art, Kai says. “We cannot just mourn this censorship case forever.

The case shows that even being small, independent, or highbrow is no protection from threat—legal or otherwise. The risks run like a current through the community, even under the cosmopolitan veneer of modern Beirut.

This year’s symposium and exhibition were dedicated to honoring artists who have experienced and captured dislocation, migration, and war up close. For at least one displaced artist—who does not want to give his name for now, and who isn’t sure where he’ll live next—the exhibition was overwhelming, too close to home while home is too far away.

This cartoonist, like several among the crowd of creators in attendance who have been displaced, found the outwardly staid presentations about free expression and storytelling to be urgent. In his decade of drawing for the Egyptian press, this artist had endured government harassment and readers’ trolling—through the 2011 revolution, the 2013 military coup, and President Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi’s ongoing consolidation of authority. (Today, tens of thousands are imprisoned on political charges, and the former general has extended term limits.). From Cairo, this cartoonist had tracked the incredible changes in the Arab world with no small amount of visual humor. His work, in contrast to that of many in the Beirut alt-comix scene, is political, and that used to be okay in Egypt, where political cartooning had a wide leeway. But today that space has shrunk considerably. This cartoonist was arrested and spent a night in an Egyptian jail in February. Then he, like other artists, writers, and critics, fled.

Now, he is trying to figure out how to write (or more likely draw) his story. In the meantime, the banal bureaucracies of consulates and functionaries hold his future in the balance while he waits on a visa.

Outside the symposium, he chatted with peers and scholars about home and statelessness. Asked about it again later that night, in the back of a busy, smoky bar, he laughed, and shared the details of his brief stint in an Egyptian prison.

Like it was for a generation in the 1960s, he said, Beirut has become a way-station and stomping ground for artists who no longer feel safe, as dictatorships proliferate and deepen across the Arab world and beyond. But it’s not something he wanted to be reminded of at that moment.

“Let’s go dance,” he said.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook