The Middle East as Old Hollywood Saw It

Come to this Beirut poster shop for the lurid stereotypes, stay for the giant killer crab.

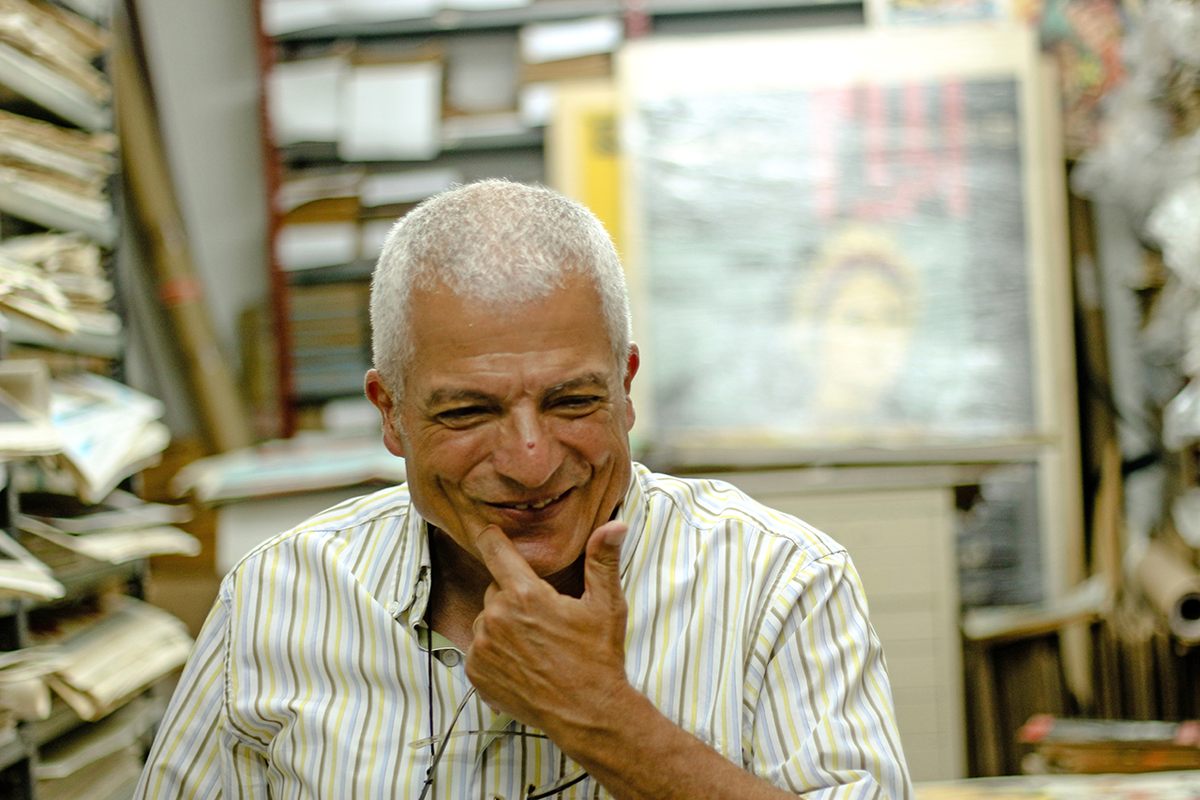

Bold, bright, breathtaking colors paired with sensational, spectacular images of magical creatures, romance, and adventure burst out of Abboudi Abou Joudé’s posters. Every surface of his shop, hidden in a back alley in Beirut, is covered in vintage movie posters that plastered the streets of Beirut from the 1920s to the 1970s. Now a white-haired man, neatly dressed in a striped shirt, he has been collecting for over 40 years, compiling thousands and thousands of posters.

Born in 1952, Abou Joudé grew up at a time when Lebanon overflowed with cinemas. He says there were over 50 cinemas in Beirut alone. Joudé would attend the movies three to four times a week, watching everything from Aladdin to Kubrick. He loved the splashy, thrilling posters, depicting electrifying romps and grandiose fantasies, but over time he noticed that certain images would repeat again and again. “I discovered that those films, or the posters of those films about Arabs, continued the imagined picture of what was thought about Arabs in the 18th and 19th centuries,” he says. “The desert, the tent, the belly-dancing, the haram, the sultan, the king. Stereotyped images continued through the posters.”

The posters pair beauty with blatant Orientalism. The films they advertise would almost universally star white actors in Arab roles, and would be produced by American directors. The headlines on the posters range from salacious Babes of Bag[h]dad to the bizarre Gigantic Killer Crab! The plots of the films feature classic Orientalist myths about passionate, savage Arab men enslaving hyper-sexualized women. These women wore skimpy belly-dancing outfits, and the action always took place in a desert, regardless of the setting.

The fantasy they presented was powerful and dangerous, says Omar Thawabeh, the communications officer at Dar el-Nimer, a Beirut arts center that recently hosted an exhibition of Abou Joudé’s posters. “Image as a tool or as a weapon is probably underrated in how powerful it is. I think what the rest of the world thinks of us is majorly based on images,” he explains. “Although we might take some of these posters with a pinch of salt and say, ‘Well, it’s just a film,’ when this becomes one film after another and generations after generations, and the images, the representation doesn’t change, it becomes more problematic.”

Thawabeh says Dar el-Nimer launched the exhibition to provoke questions around these posters and what role their fantasies play in shaping reality. He says that Orientalist tropes went beyond cinematic depictions, pointing to the infamous quote by Winston Churchill where he allegedly said, “Arabs are a backward people who eat nothing but camel dung,” according to a New York Times report in 1979.

The movie posters promote the image of Arabs as “savages, they’re backwards, they live in tents and they ride camels,” Thawabeh says. The implication, he explains, was that while Arab nations were uncivilized, Western countries were advanced: a belief that could justify the invasion and colonization of the Arab world. “We [Westerners] are civilized and we’re powerful, we have armies and developed weapons and we can conquer them, we can use them. So it starts off with dumbing down the Arab world, then it turns into this invitation to abuse the resources of the Arab world and create these power dynamics.”

The posters show how popular culture reflected the politics of the 1950s, ‘60s, and ‘70s. Abou Joudé says that prior to World War II most films shown in Beirut came from Egypt or Europe, but post-war, American films took over the market as American power and hegemony grew.

The American films initially showed a fascination and exotification of the Arab World replete with tents, belly dancers, deserts, and rich sultans. But after the 1967 Six-Day War between Israel and Egypt, Jordan and Syria, Joudé says images of Arabs began to shift, and he noticed that instead of being portrayed as heroes, they became terrorists. “The [Arab] characters became very evil or sick after the 1967 war,” he says. “It began at that time and has grown since then, especially after 2011 honestly.”

Films today reflect a new type of Orientalism, says Thawabeh. “Now there is less of a fetishization, there is still some, but now there is this dehumanization that can be very effective and that can contribute to this momentum that the extreme right wing is gaining.”

He points to the 2018 film Beirut as an example: the trailer depicts a city of smoking debris where the only Arab character is a terrorist who kidnaps the protagonist’s friend. It’s far from the everyday of Beirut with its endless hipster coffee shops, malls and restaurants.

“If you’re regular European citizen who takes all his knowledge of the Arab world from films like Beirut and series like Homeland, of course I would understand their fear of Arabs and what Arabs are going to do with Western civilization,” Thawabeh says with frustration. “So now there is less fetishization … but there is this dehumanization that can be very effective and that can contribute to this momentum that the extreme right wing is gaining.”

He says Dar el-Nimer’s exhibition aimed to invite questions about the narratives of both the past and present. “We did not feed this information to the audience. Our goal was to take a few steps away from these posters, try to look at the bigger picture and see how Arabs were represented … and see what questions you have.”

Part of the reason Abou Joudé loves the posters is that he likes to observe the changing tides of politics and beliefs through the lens of cinema. “These posters from the 1960s and ’70s show what society liked to see—adventure, war, love, and sex. Through them you can also see the development of society,” he says. He explains that today he sees less dancing, drinking, and relationships between men and women on screen, which he says reflects societal norms becoming more conservative since the ’60s and ’70s in Arab cinema. Increasing state censorship paired with rising religious sentiment in the ’80s and ’90s led to fewer risqué scenes making their way on to the big screen, a change reflected within Abou Joudé’s posters.

Abou Joudésays that when he would attend the cinema he understood that American films were portraying him as an other, but he also observed that all American “enemies” received the same cinematic treatment. “If we take American cinema for example, it’s not just Arabs. Jews were given a bad image, the Red Panic, the Germans, the Russians, the Mexicans—every ‘other’ personality in American films was seen through a racist lens … We as people sadly, show the ‘other’ in a different way … the problem exists for people in general.”

But despite seeing these tropes, Abou Joudé can’t help but remember the films with nostalgia. He remains fond of Sinbad, 1,001 Arabian Nights, and the Thief of Baghdad, even though he recognizes the stereotypes. “When I was young I loved them, I loved to save them so the people in the future would be able to know and discover this type of work that has now finished,” he says.

The posters remind him of the Beirut of his youth in the 1960s and ‘70s, of the old cinemas, and a time when posters were the only way to know which movie was on. In the back office he saves the ticket stubs of the films—keeping alive memories of long-shuttered cinemas through posters of whirling, vibrant, dangerous fantasies.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook