The Museum That Keeps Now-Obscure Confederate Flags

Beyond the “Southern Cross,” there are dozens of symbols of the Confederacy.

Last month Memphis, Tennessee, removed its last Confederate monuments, among them a memorial to Nathan Bedford Forrest, the first grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. The city sold the land on which the statues stood to a nonprofit, which quickly transplanted them to a private location. More quietly now, states and cities are deciding on the fate of these monuments and, if they are moved, where they should end up.

What should be done with objects like these? A minority of people believe Confederate monuments should be destroyed; a more popular option is to move such symbols to museums, where the history they represent might be remembered without being reified.

There are already examples of what this type of preservation looks like. In Richmond, Virginia, the American Civil War Museum, formed from the Museum of the Confederacy and the American Civil War Center, has a unique Civil War flag collection, made up predominantly of Confederate flags, still controversial symbols of the ideas the Confederacy stood for.

Stored carefully away, these flags are held as valuable pieces of history, with the idea that they should be preserved and remembered in a place that can share and display them within a context more educational than ideological. “These things are part of the fabric of history,” says Cathy Wright, a curator at the museum. “Museums seem to be the safe place to explore these, and that is in fact where they belong.”

In museums, these symbols might be remembered and forgotten at the same time. The American Civil War Museum’s collection includes many examples of one of the most enduring symbols of the Confederacy, the well-known “Southern Cross” battle flag, which in the 20th century was adopted as a symbol of opposition to the civil rights movement. The collection also includes dozens of other Confederate symbols and flags, now obscure to most Americans, that were designed by different commanders or women from soldiers’ hometowns.

Of the museum’s more than 820 Civil War flags and flag fragments, some are reproductions and post-war flags. But more than half come from the conflict itself, many captured by Union soldiers.

During the Civil War, flags acted as signals to soldiers—to retreat, advance, and veer in other directions. They had to be big and bold, and the men who carried the flags made easy targets, especially as they could not hoist a flag and wield a weapon at the same time. Capturing a flag was considered an act of valor, worthy of a Medal of Honor. To qualify for the medal, Union soldiers had to turn seized flags over to the War Department, which forwarded them to Washington, D.C.

“They were kept as trophies, but they weren’t that prominently displayed,” says Wright. “A lot of them have evidence of being severely moth-eaten or kept in damp conditions.” In 1905, Congress returned the captured flags to the states where they had originated, and a year later sent hundreds of unidentified flags to Virginia, which handed them over to the Museum of the Confederacy.

At the time, the museum was not an institution that aimed for a neutral reading of history. Founded by society ladies in Richmond in the 1890s, it began as a shrine to the Confederate cause, filled with memorabilia sourced from Confederate sympathizers. (Over time, the museum began aiming for a more scholarly approach and, in 2013, combined with Richmond’s American Civil War Center, which had a much smaller historic collection but a broader perspective.) The first flags in the collection, donated before the museum even opened, might have been sent home earlier in the war or been brought home by Confederate soldiers who hid the flags under their clothes.

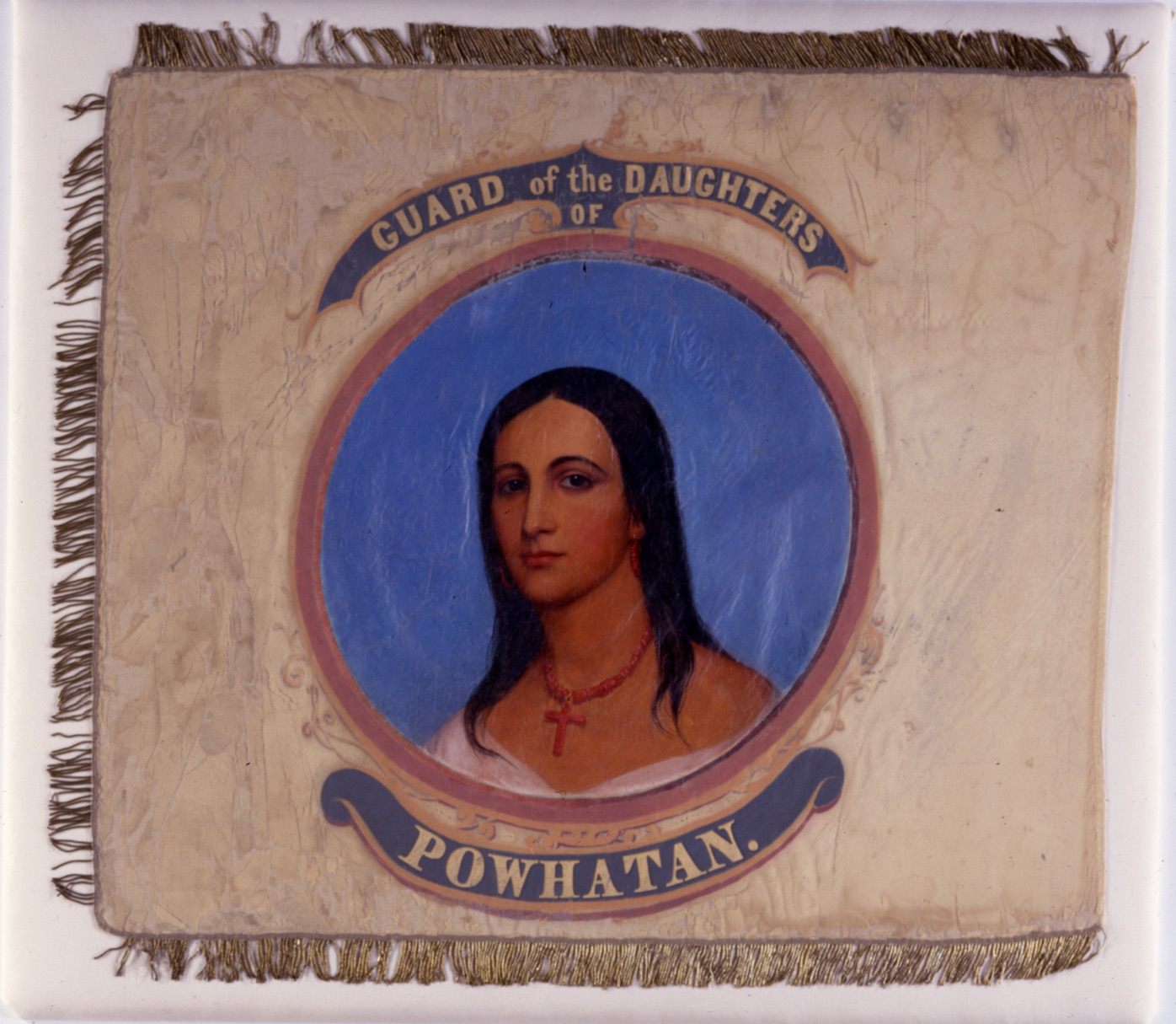

At the war’s outset, women often commissioned or created unique flags for local regiments. There’s a flag in the museum’s collection that has one word—“Home”—on its front and was made from a woman’s wedding dress. Another, from Virginia’s Powhatan County, features a portrait of Pocahontas. One delicate flag features a portrait of a company marching with an angel overhead; the other side show the Virginia state seal, modified so that the goddess of virtue has her spear raised overhead. Some of the flags are small, such as the miniature one a Missouri woman sewed into the hem of a dress. Naval flags, on the other hand, can be 12 feet long.

At the outset of the war, there was little coordination of what flag Confederate regiments should carry, and many carried newly created state flags. The first Confederate national flag, the “Stars and Bars,” resembled the American flag too closely. The second, known as the “Stainless Banner,” was later abandoned because its white background made it look too much like a flag of surrender.

By 1862, generals were allowed to pick flag designs for the regiments under their command. Today’s most famous design was used, in a square form, by the Army of Northern Virginia, led by General Robert E. Lee. But General William Hardee used a blue flag with a full moon in the center. General Earl Van Dorn had a red flag with a crescent moon and 13 large stars. At the time these symbols would have been well known, but they have since become less instantly recognizable as symbols of the Confederacy.

In its own time, the square form of the Confederate battle flag was prominent, and the same design was used by the Navy (in rectangular form) and the Army of Tennessee. A similar take, minus one star, was used by Forrest’s troops—an affiliation that contributed to its revival in the 20th century and its association with white supremacist groups.

“It became used and abused in all the ways we know,” says John Coski, the museum’s historian and author of The Confederate Battle Flag. “The others benefit by their relative obscurity.”

But even when symbols like these are kept in museums, they can retain their symbolic power. In the American South, some people now fly the first national flag of the Confederacy instead of the more famous one. Its design is also incorporated into Georgia’s state flag. “They’re exploiting the fact that no one recognizes it,” says Coski. “It enables them to have their cake and eat it too. They don’t want to give offense.” Other groups, he adds, ones that want to show that they don’t accept the death of the Confederacy, may fly the third national flag, the “Blood-Stained Banner.”

In the museum, however, these flags can become meaningful in new ways. One of the Confederate battle flags in the museum’s collection may be the only flag captured by black Union soldiers that was turned into the War Department. Today, says Wright, the curator, the collection’s visitors include descendants of Union soldiers, and they are interested to see the flags their ancestors captured. Some have contributed funds for preservation and even donated the Medal of Honor earned for a flag’s capture.

“I do think museums are a place of preservation not only of the artifacts but of memory itself,” Wright says. “How we remember probably changes from generation to generation. In the future people might be asking different questions. They might want to look at things differently.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook