What’s the Most Striking Image of Earth?

NASA’s Earth Observatory wants your help finding hidden gems in its vast archives.

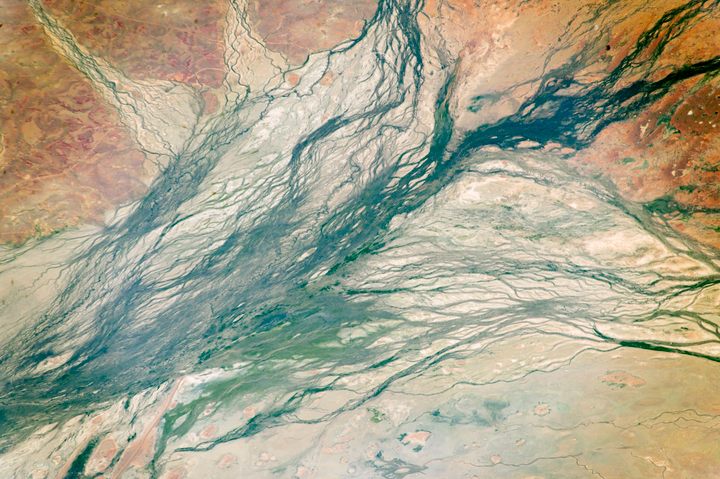

For more than 20 years, NASA’s Earth Observatory has collected and shared images of our planet, as it appears from far above the Earth’s surface. Some capture the entire marbled globe, while others are zoomed-in and abstract. A smattering of holes that could be the work of termites are actually towering sand dunes and desert lakes. Swirls of beige, mauve, and olive green may look at first like brushstrokes in an Impressionist painting, but they turn out to be mud and water mingling in Lake Frome, a saltpan in central Australia.

Over the decades, the Earth Observatory has published more than 15,500 images. They vary in detail, scale, and origin—some were captured by astronauts, others by satellites—but they collectively “tell a story of a 4.5-billion-year-old planet where there is always something new to see,” writes Michael Carlowicz, managing editor at the NASA Earth Observatory, in the foreword to the 2019 book Earth. “They tell a story of land, wind, water, ice, and air as they can only be viewed from above. They show us that no matter what the human mind can imagine, no matter what the artist can conceive, there are few things more fantastic and inspiring than the world as it already is.”

Now, the Earth Observatory is asking readers to nominate the image that left them especially rapt and riveted. You can submit ideas until March 17. (So far, the many suggestions include a 2015 composite of Earth rising above the lunar surface—a nod to a famous 1968 image—and a recent image of melt ponds in Antarctica, captured after the highest temperatures ever recorded there.) Atlas Obscura exchanged emails with Carlowicz about satellites, telling stories with data, and the wonder of a fresh view of our home planet.

How are the images captured?

The vast majority of our natural-color imagery comes from the MODIS instruments on NASA’s Aqua and Terra satellites, from the Landsat satellites (Landsat 5, 7, and 8), and from the VIIRS instrument on the Suomi-NPP satellite. Every weekend, we publish a photo shot by the astronauts. Occasionally we get aerial photos from scientists and engineers on field/airborne campaigns.

For a long time, we used imagery from the Earth Observing-1 satellite (until it reached the end of its life). But we also regularly make maps, plots, and data visualizations based on data from dozens of other instruments, models, and scientist-provided analyses. My guess is that 200 different instruments/sensors are represented in our archives/catalog.

How do you find a story in the reams of data? Do you start with a question and look for an image to illustrate it, or begin with data and then build the story around it?

We do both. Images on Earth Observatory are always accompanied by a story; stories always have to have a strong image (or several). Our site is based on the interplay of images and words—both are needed, and both should reinforce each other.

We approach storytelling like journalists because everyone on the staff comes from a journalism or data journalism background. We read the news and social media to track natural events and hazards, and then we look for imagery or data that can help people understand what the planet is doing. (Sometimes this means we do not tell a story because we cannot see it—the scale is too small for our satellites, or clouds are in the way, or timing is off, etc.)

We scan and read scientific journals for interesting papers, and then work with scientists to convey those concepts in ways that non-scientists can understand. We attend lectures or seek out scientists and engineers in the halls of NASA and other science institutions. We pay attention to the human and natural calendar and look for images and stories that fit the seasons and moments.

Sometimes we find—or scientists share with us—compelling imagery and we ask: What is that? And then we follow our curiosity in reporting. We consider an image and think: What can we say that isn’t obvious from the image? Is it scientifically interesting? Does it convey a timeless or timely scientific idea? Is it just beautiful or wild?

We look for a NASA hook or contribution because we are here to help tell the story of Earth as NASA sees it. Is it imagery or data acquired by NASA? Is it data from a close scientific partner that is shared with NASA-funded scientists? What does NASA bring to this story? Why should we tell it?

Do you have a favorite of the Earth Observatory’s images of Earth?

I honestly do not have one favorite image or story. (I edit all stories and visuals.) I am the current front man for the band, but it wouldn’t be the site that it is without the help of a lot of creative and diligent colleagues—writers, data visualizers, scientists, web developers—who are constantly pushing each other to be better.

I have written a lot about the Earth at night, and I remain fascinated by what we can see. I do have a fondness for places that I have visited—favorite childhood or vacation spots. I have lived most of my life near the coast, so those places are a bit over-represented in my portfolio.

What visual qualities do you look for in an image to share with a broad public? Do they seem to have something specific in common?

We ask a few things for every story: What story are we trying to tell, and what is the best way to show that? If we start from the image, we ask: can we reliably explain what we see there? How do we know—how can we verify—what that is? Is the image visually compelling? What draws your eye when you look at the image? Will this visual be understandable to our grandparents, our children, our non-scientist friends? (For this reason, we try not to use a lot of false-color because research and experience shows that most people don’t understand it.) Can you actually see the action, the details, the concepts that we want to convey? We are not just here to share pretty pictures.

There is repetition to the cycles and seasons and events on Earth. But we are constantly thinking about whether there is a fresh and novel way to present things. Publishing 365 days a year—and for 21 years—that can be a challenge. We try to stay vigilant and creative. We are always hunting for new angles and ideas.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook