The Early Master Plans for National Parks Are Almost as Beautiful as the Parks Themselves

In the 1930s, park planning was pretty.

In the beginning, there was Yellowstone: more than 2,000,000 acres of mountains, fields, forests, geysers, and rivers, a place of such commanding beauty that, according to an early account describing the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, “language is entirely inadequate to convey a just conception of the awful grandeur and sublimity of this masterpiece of nature’s handiwork.”

Yellowstone was declared the country’s (and the world’s) first national park in 1872, and by the time the National Park Service (NPS) was established in 1916, the program had grown to include Casa Grande Ruins, Rocky Mountain, Sequoia, and Yosemite, among others. After President Franklin D. Roosevelt reorganized and expanded the NPS in 1933, there were 137 parks and monuments across the country (today, the National Park System includes 417 areas, including the White House)—all of which required, and still require, significant management and planning.

The first master plan—a document packed with maps and recommendations for preserving and monitoring a park and the visitor experience—was drawn up in 1929 for Mount Rainier National Park, 369 square miles in Washington state. It was created by Thomas Chalmers Vint, landscape architect and, from 1933, Chief of the NPS Branch of Plans and Designs. It served as a kind of blueprint for the plans to come, and included proposals for a new hotel complex and an expansion of the facilities on the south slope of the glacier-covered volcano.

Throughout the 1930s, a series of master plans for parks and monuments followed. They became the essential documents for the management of every square mile of protected land. “Its use is to steer the course of how the land within its jurisdiction is to be used,” stated Vint. “Each project, whether it be a road, a building, or a campground, must have its construction plan approved. In the course of approval it is checked as to whether it conforms with and is not in conflict with the Master Plan.”

Vint was a crucial figure in the early decades of this form of park planning. When designing or overseeing the design of facilities for national parks, his priority was to complement the natural environment. “The work has to do with the preservation of the native landscape and involves the location and construction of communities, buildings, etc within an existing landscape,” Vint wrote in a 1928 analysis.

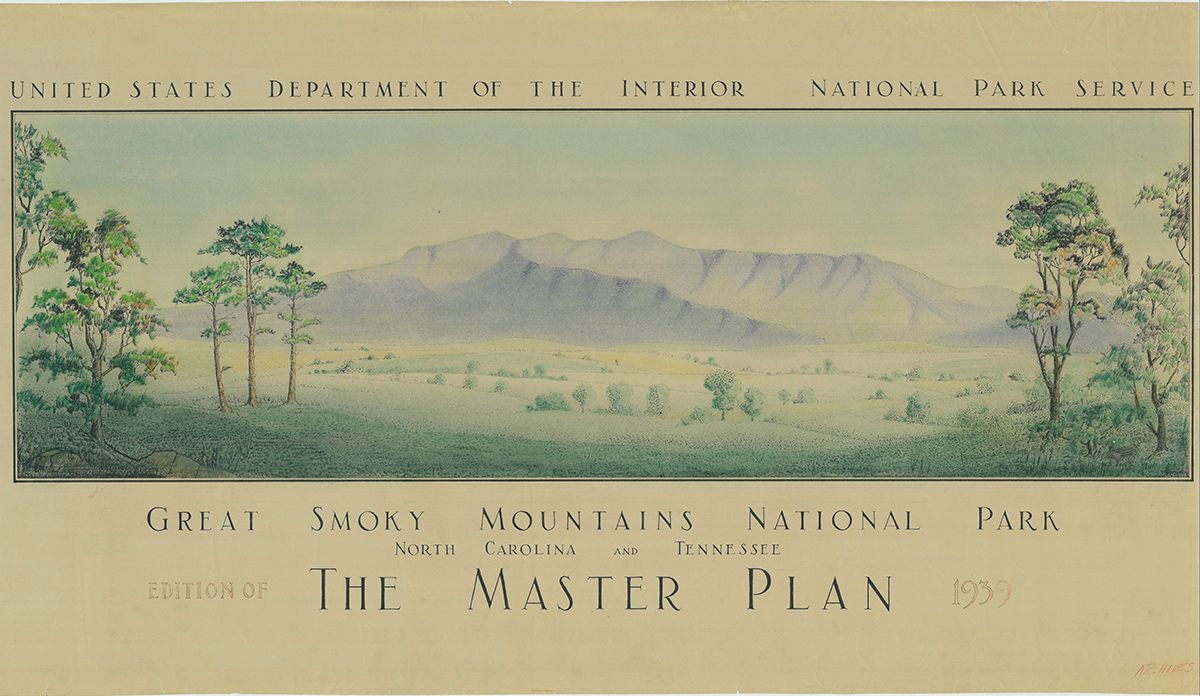

The plans themselves, drawn up by resident landscape architects, often featured decorative covers, an excerpt about the purpose of the park as stated by law, and plans for existing and proposed facilities. As Brandi Oswald, Cartographic Archivist at the National Archives (where the original plans are now held), notes, “the plans contain valuable information about the development of our national parks.” They might include access points by road or rail, hiking trails, museums, lodgings, and administration buildings—all of which is crucial in satisfying the overarching goals of the NPS: to conserve scenery, history, and wildlife, and provide for their enjoyment.

The cover images for these plans are particularly striking, and including either hand-drawn illustrations or hand-colored photos, and neat, elegant lettering. Many parks had multiple editions over the years as conditions and proposals changed. The Dinosaur National Monument plans from 1939 and 1940 kept the same cover but recolored its dinosaur from a dull beige to a vibrant green.

By contrast, the 1936 plan for the Vicksburg National Military Park has a evocative, somber, charcoal cover featuring a bare tree and a row of cannons, while the 1939 edition shows a cheerier green vista with trees (though it still contains a cannon). Unfortunately, none of the plans are signed, so the artists behind the cover illustrations remain unknown.

The master plans held at the National Archives Cartographic Collection are a little-seen glimpse into the early years of stewardship of America’s national parks—for all to enjoy, now and in generations to come. Atlas Obscura has a selection of images from the plans.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook