Visitors Can Touch Human Brains at This Indian Neuroscience Institute

It’s like a petting zoo for organs.

When the woman died, the police took away her husband. Her parents claimed he had driven her mad, harassing her for dowry payments. True enough, the clinical history that arrived at the mortuary along with her body listed what appeared to be psychiatric symptoms: manic behavior, auditory hallucinations, strange, distorted visions.

It was only once her skull was broken open, her brain removed and segmented, that the truth was revealed: her injury was physical, and inflicted not by her husband, but by a tapeworm.

Visitors to India’s only Brain Museum, in the southern city of Bengaluru, know the woman only as “neurocysticercosis - cerebral.” That’s how a small, typed label identifies the slice of her brain that lives here, pickled in formalin and encased in hard clear plastic, like a macabre paperweight or a uniquely unwhimsical snow-globe.

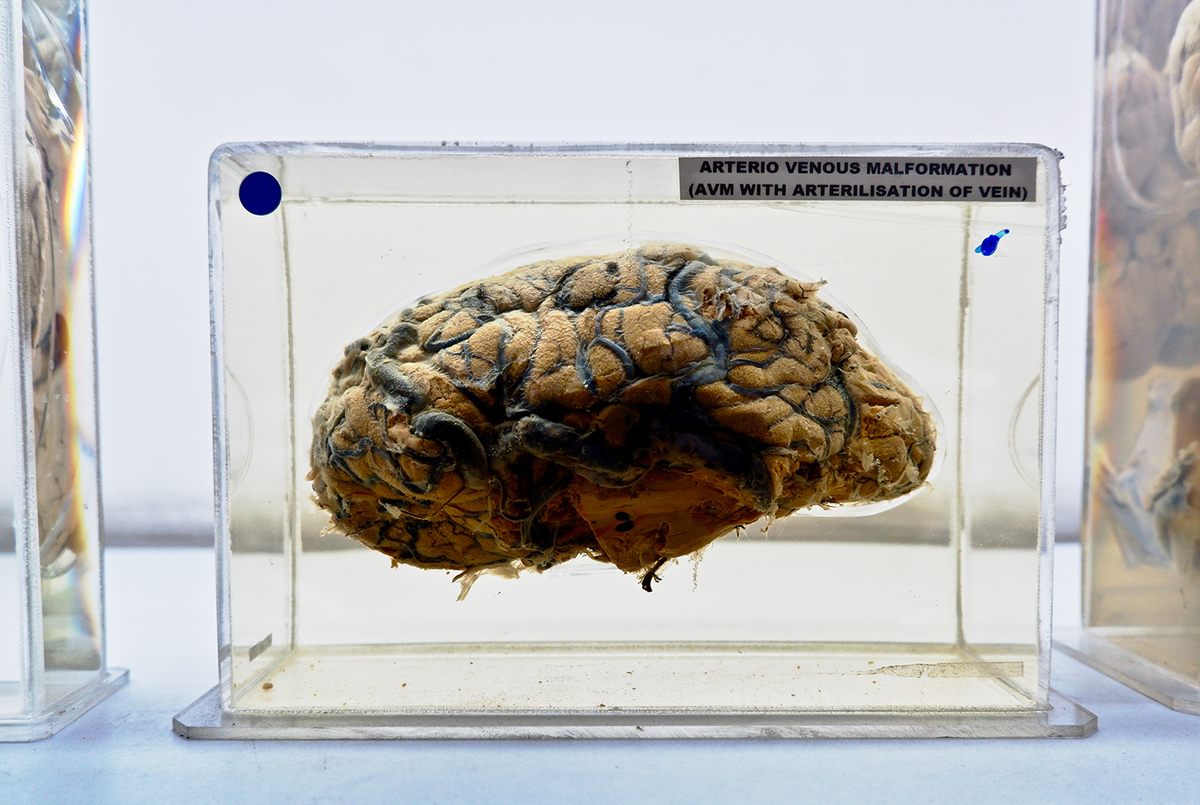

There are hundreds of specimens, all similarly preserved and mounted, arrayed on LED-backlit shelves that stripe three walls of the single, largish room. Among them are cross-sections of brains marred by aneurysm, fungus, bacterial infection, and trauma. Some are warped by tumors, dense and distinct, like thick fleshy mushroom-stems pushing out through the softer, crumpled brain tissue. Others are partially shrunken by birth defects or Alzheimer’s. Cuboid specimen cases contain entire brain hemispheres, spidered with thickened dark veins.

“Neurocysticercosis - cerebral” is a sliver about half an inch thick, strafed through-and-through with holes approximately the size of pepper-corns—evidence of an infestation of larval pork tapeworms. “The importance,” explains Dr. S.K. Shankar, “is that this was a misdiagnosis.” He goes on, “we make mistakes in clinical medicine. But this”—he gestures at the wall of brains—“tells you the final diagnosis.”

Dr. Shankar, a neuropathologist, has been a part of the museum’s story from the beginning. Now in his early 70s, he is a man of a compact stature and brisk manner; he wears a clipped white mustache and a reputation for exacting standards. He retired in 2012, and has shown up to work every day since. “He makes us tick, I think—as a team,” says Dr. Anita Mahadevan, who has worked alongside Shankar since 1998. His colleagues say that the museum was his idea, but when I ask him about that, he shrugs off the credit: everything, he insists, has been a team effort.

The team in question is a group of scientists and technicians at India’s National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, or NIMHANS, which houses both the museum and its twin project, the Brain Bank. Shankar joined NIMHANS as a young researcher in 1979. That same year, he and other pathologists began to establish the permanent collection: brains with interesting, plainly visible pathologies, were gathered at autopsy, and if the family members of the dead person consented, the brains were bathed in a formalin solution for a minimum of three weeks until they grew firm enough to slice, and durable enough to survive on display.

For years, the growing exhibit made its home in a small room, accessible only to medical professionals, researchers and students. “The students rarely get to see specimens like this. They see a patient. The patient dies, and they assume what has happened,” Shankar says. “But here there are no assumptions.”

In 2010, a new building, the blue-glazed Neurobiology Research Centre, opened up on NIMHANS campus, and the museum was shifted into this larger space. Dr. Shankar and his colleague, Dr. Anita Mahadevan, spotted an opportunity to open the exhibit to the public. By 2014, thousands of visitors had toured the exhibit. It had a new objective: “neuroscience literacy” for the curious masses.

“This museum is about the brain, and the stories of the brain,” says Shankar. Here among all his “stories,” he reminds me of a librarian, interrupting himself mid-anecdote to run a finger along a shelf and pull down another title for me to peruse: “atherosclerotic cerebral atrophy,” perhaps, or “Japanese encephalitis.” He presses them into my hands mumbling, “hold this,” and “put these on the table, there.”

Formalin is such an effective preservative that it is difficult to visually distinguish, among the examples Shankar has culled from the shelves, decades-old brains from recently mounted ones, but Shankar remembers which sample arrived when. “All are my babies,” he jokes, when I ask if he has a favorite.

The woman who became “neurocysticericosis – cerebral” arrived on the NIMHANS mortuary slab early on in the museum’s history. As a matter of procedure, her identity has been “de-linked” from her tissue contribution. If anybody still knows her real name, it’s Shankar. But he’d never say: doctor-patient privilege applies even when all your patients are dead.

Their anonymized tales, however, are there for the telling. Some of them even have a moral.

When Shankar’s team discovered the worm-tunnels in the woman’s cerebrum, her husband was released from police custody. Her parents abandoned their accusation. The family, I presume, got on with the unspectacular labor of grief. The pathologists’ “final diagnosis”—beyond clinical error, beyond assumption—had, in other words, a cooling effect. The inflaming forces of mystery and suspicion were dampened by straightforward encounter with the actual substance of her brain.

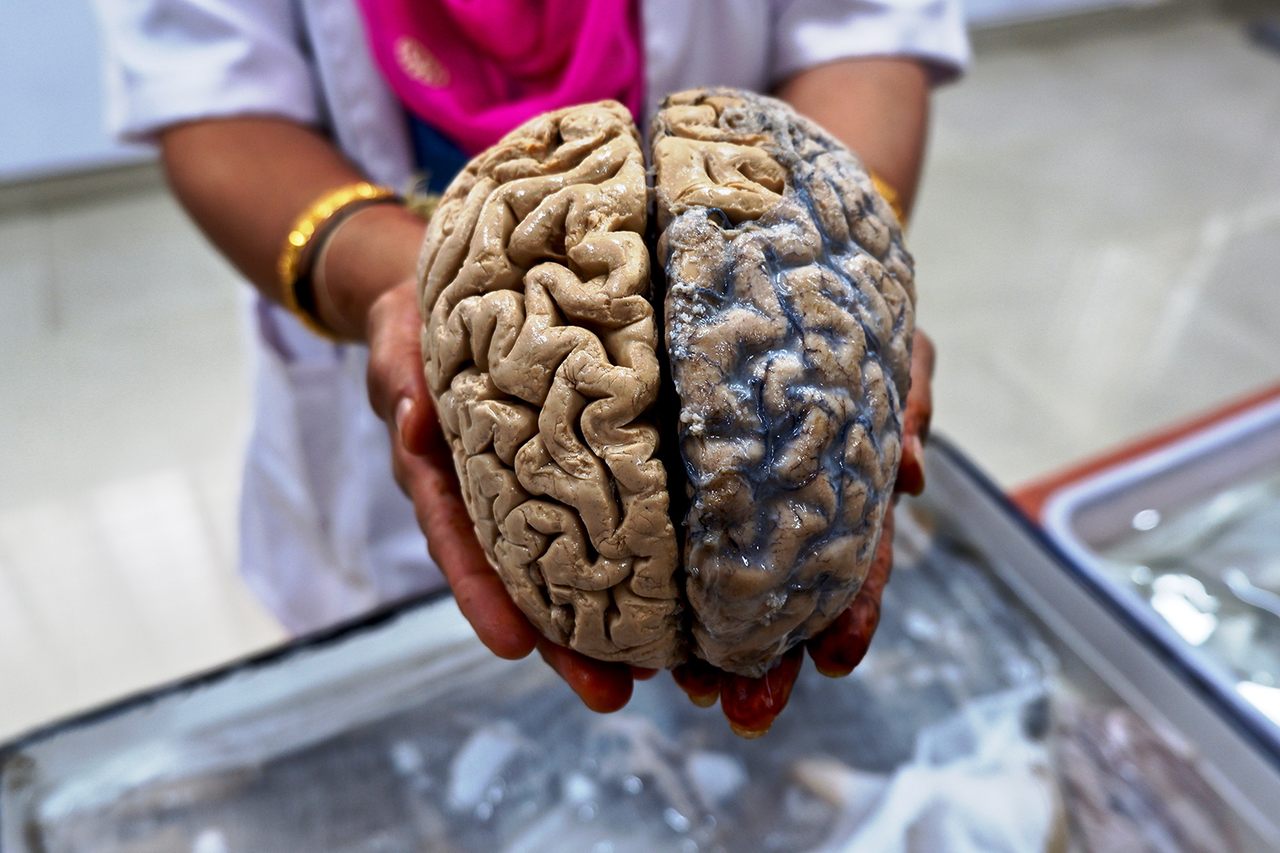

Perhaps this—a belief in the power of a direct experience—is why the Brain Museum’s staff encourage visitors to reach out and hold real human brains, slick from their pickling baths, in their untrained and ungloved hands.

Unlike the brains in plastic, these specimens are “normal”—healthy, that is, though it’s a strange word to use for a piece of a dead person. Really, it means that the brain’s owner died of something else, an affliction elsewhere in the body. It’s possible that they were a donor who pledged their organs before their death, but usually, the source was an unwitting victim of a fatal traffic collision; road deaths are wildly common in Bengaluru. In these cases, it’s a city police officer, rather than a treating clinician, who calls up the NIMHANS pathologists to ask for a “cause of death” pronouncement. Autopsies are the only opportunity for the scientists to directly ask families to consign their loved ones’ earthly remains to this peculiar afterlife.

On my first trip to the museum, there are two whole brains and several other organs—lungs, livers, a heart, the vermicelli mess of spinal nerves, spilling from a split sac—paddling an inch or two deep in a white enamel basin on a table in the center of the room. Bundled in knotted cheesecloth, there is a third brain, this one segmented. The scientist leading the public tour I’ve joined walks her fingers over the slices, as if she’s flicking through a rolodex, to find the cut that will best reveal the seahorse-shape of the hippocampus. She palms the pickled body parts carefully into our cupped hands. I feel, suddenly, like I’m in some kind of eccentric petting zoo.

The intact, formalin-fixed brain is weighty, unitary, stable even at the join of its two halves, and in texture, like an elastic paté. The school-kids who visit the Museum on field trips tend to compare it to tough paneer. Fresh brain is more jelly-like, I’m told. But even in its hardened state, the fleshy, ordinary realness of the organ—the theater of all thought and all emotion—lands a little bit like an epiphany; like the curious inverse of a paranormal experience.

Shankar and Mahadevan use the word “demystification” to describe what they hope the museum will achieve. In India, where illnesses of the brain are often met with stigma and superstition, it’s a word that has a particular, practical resonance. “People think these neurological diseases are something like an evil spirit. We want to remove that idea,” Shankar tells me. Posters on the museum’s walls target epilepsy in particular: “continuous treatment effective,” declares one. “Active life possible!”

Dr. Vijaya Nath Mishra, a neurologist at Banaras Hindu University in the ancient northern city of Varanasi, has spent 20 years working on epilepsy and its stigma. “Epilepsy is considered as a curse of bad evils, and thus, the epileptic patients are abandoned and discriminated from society,” reads a research paper he co-authored this year. A 2012 study published in the Lancet found that only 60 percent of urban epileptics and 10 percent of rural sufferers in India approached clinicians for treatment. The remainder, according to Mishra and his colleagues, rely on “spiritual and witchcraft practices.”

“I feel often helpless when we see the suffering of these patients,” Mishra wrote to me in an email. He has seen an 18-year-old girl brought to hospital in chains. Countless epileptics are abandoned by their spouses, or rejected as prospective marriage partners. On WhatsApp, he sends me videos shot during field research in remote parts of Uttar Pradesh. In one, a man Mishra describes as “learned” insists that the best treatment is to give a baby monkey to the patient. As it grows up, it will lure the disease into its own body, like an animate portrait of Dorian Grey. Another man prescribes the swallowing of bed bugs.

“These superstitions are nothing but the thought processes of human beings about an organ they have never seen,” Mishra tells me over the phone. The brain is hidden, he explains: the heart beats, the stomach growls or aches, but the brain is imperceptible—“always a mystery in life.”

In death, however, lies an opportunity for a course-correct. Mishra visited the Brain Museum in Bangalore in 2003, for a 15-day graduate course in neuropathology. “I was thrilled,” he remembers. “I was very happy to hold a full brain in my hand.” It was a first for him, and it made an impact. Now he carries photos of brains with him when he travels, and dried apricots as small, tactile stand-ins—antidotes to abstraction. “This is your brain. It is soft. It doesn’t break like a bone,” he tells epileptics he meets. “Then they know they can treat it.”

He also carries his donor card. Before his fortnight in Bangalore was up, 15 years ago, Mishra pledged his own brain to the pathologists at NIMHANS.

Dr. Anita Mahadevan, who, since Dr. Shankar’s retirement, runs both the Brain Museum and the Brain Bank, has been delayed. A man has died, and autopsy can’t wait long. When she arrives, she fills me in: the patient’s tuberculosis had spread to his brain, causing vomiting and seizures in his final hours. His referral to NIMHANS came too late to save his life.

Mahadevan has a good teacher’s attitude of focused, benign attention when she speaks. Her enthusiasm for her work is magnetic: “I want to make people realize that it’s such a beautiful organ,” she says. She has always wanted to be a pathologist. “Surgeons are doers. They want to set things right,” she explains. “Pathology is like solving puzzles. Pathologists are detectives.”

The good news, from a sleuth’s perspective, is that the man’s family has consented to donate his brain for research. In fact, refusals are rare. “Mostly the attitude is: my family member has died. Let someone else’s live,” Mahadevan says. “There’s a lot of altruism.” So half of the man’s brain will be kept frozen at -80 degrees C (-112F) in the NIMHANS Brain Bank, an archive of tissue kept by for future research.

The other half—the domain of the museum—will be fixed in formalin, making it useless for biochemical testing but stable enough for analysis under the microscope. This particular brain will likely not be mounted for display. That’s a distinction typically reserved, in the words of Shwetha Durgad, a Ph.D. student who works on the museum team, for “picture perfect” specimens: the ones with obvious, dramatic lesions.

But despite the altruism of the bereaved, Mahadevan is facing a supply problem. This is only her fourteenth specimen of the year. “World-over, the rate of autopsies has declined. We used to reach almost 300 per year—that was before the MRI,” she says.

Modern brain imaging allows doctors to spot problems sooner, and save more lives. But when patients die, the shadow-pictures generated by the huge, looping MRI rig have often already produced a reliable-enough diagnosis: doctors have little incentive to ask for an autopsy, and family members little reason to agree to one.

Had the woman called “neurocysticercosis – cerebral” fallen ill in the years after NIMHANS acquired an MRI machine, or even a CT scanner, she might never have been misdiagnosed as psychotic: the tapeworm pits would have been clear in the ante-mortem images. But had she died anyway, her physicians might have declined to call a pathologist. Her specimen might never have wound up on the museum shelf.

That’s a problem for scientists like Mahadevan, because while an MRI might tell you what’s going on, there are further questions that need to be asked. “Why is the nerve cell dying? What can we do to prevent it? Can we find a treatment? All this requires brain tissue, on which you can do a biochemistry, look at electron microscopy, use omics technologies,” Mahadevan explains. The investigative tools are improving, even as the stocks of diseased brain tissue are in decline.

And the NIMHANS pathologists only have the capacity to perform autopsies within a limited geographical radius. While Mahadevan gets to work trying to kick-start satellite brain banks across the country, living, local organ donors are growing ever more important.

Which means that the Brain Museum’s hoard of unchangeable, picture-perfect specimens are stepping with fresh urgency into their ambassadorial role: advocates for science. A stack of cards with information about the organ donor scheme sit on a table by the door. “First we give the museum visit, then we tell about donation. If people are interested, we give them a card,” Shwetha Durgad tells me. The pledge numbers are slowly ticking upwards.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook