What Can We See in the Oldest-Known Photographs of Kandahar?

These 72 images are a rare glimpse of an ancient city lost to time and conflict.

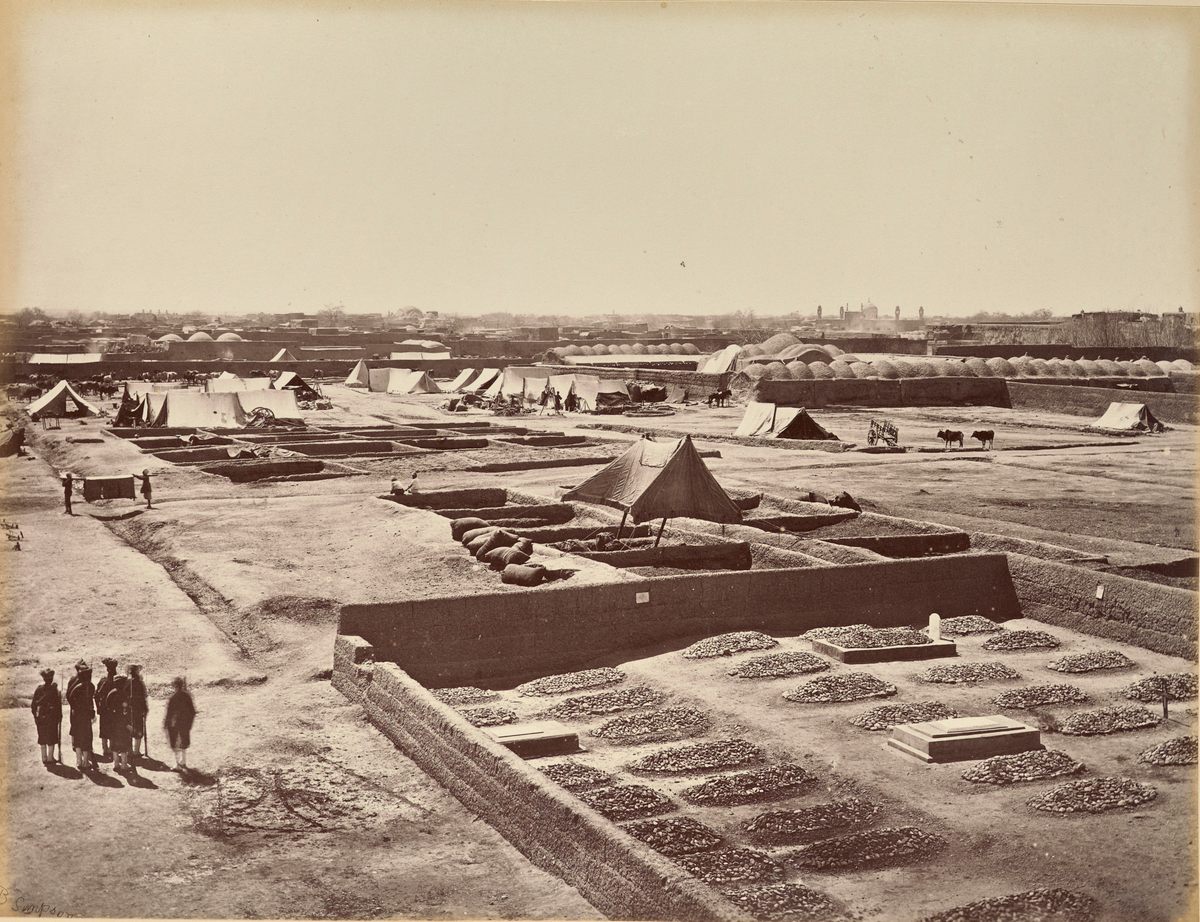

Benjamin Simpson arrived in Qandahar, Afghanistan, in late 1880, at the end of what would become known as the Second Anglo-Afghan War. Simpson, a British surgeon assigned to the Indian Medical Service, had been sent to the strategically located city not only as a military doctor, but also as a documentary photographer, tasked with creating a visual record that would serve a bevy of purposes, including for surveillance, military intelligence, and propaganda directed at the British public. When he left the following April, along with the rest of the British Army, he carried with him images of an ancient city under siege, rare glimpses of a place now lost to time—and to decades of conflict.

“These amazing, sweeping views seem to be the earliest images of the city,” says Frances Terpak, curator of photography at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles, which recently acquired and digitized one of two known copies of the 72-plate album (now available in an immersive virtual exhibition, At the Crossroads: Qandahar in Images and Empires).

Nineteenth-century Qandahar—today generally spelled “Kandahar”—was renowned for its massive walls, nearly 30 feet thick at the bottom and more than 26 feet high. Inside were important Islamic sites like the Shrine of the Cloak, which held—and still does—a garment believed to have been worn by the Prophet Muhammad. Bazaars buzzed with traders selling carpets, camels, sheep, silks, leather, and metalwork from Iran, India and across Central Asia. These goods, along with news and ideas, traveled daily through the city’s six huge gates, each named for a city with which Qandahar had an important economic relationship.

It was that role as a hub of trade that convinced the British military of the city’s strategic importance in the proxy war they were then fighting with Russia. Where the tsar hoped to expand his holdings, the British were protecting their interests in India—the “jewel in the crown” of Queen Victoria’s empire. The British had secured Qandahar after a hard-fought 1880 battle against Afghan forces, but the war overall was going poorly. By the time Simpson traveled to Qandahar, parliament was debating whether to withdraw.

Simpson would have brought his own heavy camera and hundreds of pounds of equipment, including glass plates and chemicals—logistical challenges that reveal the importance of the assignment to his superiors, who may have used these photographs to inform their strategic decisions. And Simpson was a thorough documentarian, capturing bustling street scenes, views of the landscape beyond Qandahar’s walls, images of the British occupying forces and portraits of ethnic groups who lived and worked in the area.

“The album is really one-sided, taken from a British perspective,” Terpak notes. “They were gathering information on who would be sympathetic, where they could find more camels, where they could get enough food, the terrain—basically, how and whether the British can control the region.”

For all their imperial strength, the British were ultimately not able to control Afghanistan, and when they left Qandahar in 1881 they never returned. Simpson’s album was soon forgotten, with the only other extant copy tucked away in the archives of the Royal Geographic Society. (The Getty’s is believed to have been passed down through the family of a military officer who served in Afghanistan.)

Qandahar, meanwhile, saw a century of peace followed by 40 years of conflict. It was a center of mujahideen resistance during the 1979-1989 Soviet-Afghan War, then, in the 1990s, the capital of the fundamentalist Taliban government, whose ties to the Al Qaeda terrorism network led the United States and its allies to invade after the September 11, 2001 attacks.

Modern Afghanistan has endured perhaps more than its share of history, with the ironic result that much of its past has been destroyed or rendered inaccessible to its people. That makes this album all the more valuable, notes Jawan Shir Rasikh, an independent historian who is working on a book about the region, and who recently appeared on a panel discussing the Simpson album on TOLOnews, Afghanistan’s equivalent of CNN.

“Kandahar is an extremely important place in the history of civilization,” Rasikh says, in a Zoom interview with Atlas Obscura. “This album represents a rare source from a very important period, and there’s a richness to the information there that’s worthy of a dissertation.”

Rasikh grew up in Kabul, the son of a teacher and a civil servant, and like all young Afghans, his life has been shadowed by conflict—and that was before America’s 20-year War on Terror, which ended last year with U.S. forces’ abrupt departure and the Taliban’s return to power. But it’s important to Rasikh, who lives in Toronto* but plans to return home one day, that Afghanistan be seen, especially by Afghans themselves, as more than a warzone. These pictures can play a part in that, he believes. It’s why he lent his expertise to TOLOnews, and why he also hopes that the photos might one day be exhibited in person in Afghanistan.

“I have been always interested in how we can transfer what is produced about Afghanistan in North America and in Europe and elsewhere to the people of Afghanistan,” he says. “It has been my intellectual and personal commitment to make sure that the people know that they had a very complex past—one which was not just black and white.”

*Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated where Jawan Shir Rasikh lives.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook