An Olmec ‘Earth Monster’ Returns to Mexico

The repatriation of an ancient sculpture highlights the influential early Mesoamerican culture.

This story was originally published on The Conversation and appears here under a Creative Commons license.

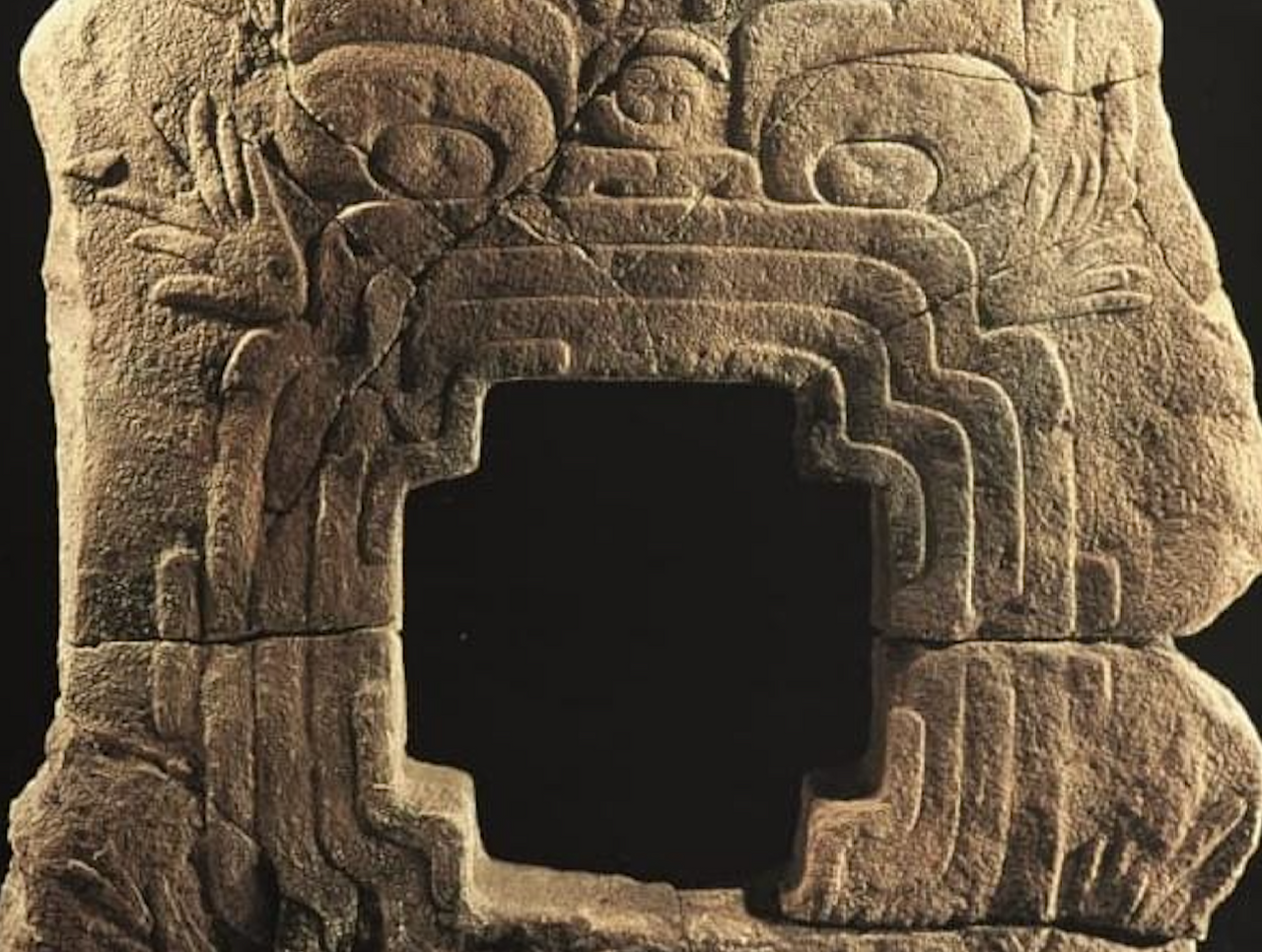

An extremely important 1-ton sculpture, sometimes referred to by archaeologists as an “Earth Monster” or Monument 9, was repatriated to Mexico from a private collection in Colorado in May 2023, according to an announcement from Mexico’s Consul General in New York. The monument features the head of a front-facing creature with a gaping mouth: a supernatural being that represented the living, animate earth to an ancient culture in Central America and Mexico.

This sculpture was reportedly found at the base of a hill at Chalcatzingo, an archaeological site some 80 miles (130 kilometers) south of Mexico City, and dates to roughly 600 B.C. Chalcatzingo is closely related to Olmec culture, one of the earliest in ancient Mesoamerica.

I am an archaeologist specializing in Mesoamerica: an area that encompassed present-day southern Mexico, parts of Costa Rica and all of Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, El Salvador, and Nicaragua. I have visited Chalcatzingo many times while researching the development of this rich cultural region.

Many scholars regard the Olmec as the “mother culture” of ancient Mesoamerica, a civilization where particular types of monumental architecture, sculpture and gods originated. Among the later Maya, for example, the gods of wind, rain and corn—or more precisely, maize—are clearly derived from the earlier Olmec culture.

The Olmec heartland was in what are now the Mexican states of Tabasco and southern Veracruz, along the southern coast of the Gulf of Mexico. Much of their influence was based on economic wealth from corn.

Of Olmec art that has survived the centuries, their carved heads are particularly striking and well known. By 1000 B.C., Olmec sculptors at San Lorenzo, Mexico, had fashioned no fewer than 10 colossal heads, all over 6 feet high. Archaeologists believe these are individualized portraits of rulers, each with their own specific headdress: depictions of specific people, which is quite rare in New World art.

The Olmecs were also masters in the carving of jade. I was involved in locating the original Olmec and Maya jadeite sources in highland eastern Guatemala, found in stone outcrops often located about 6,000 feet above sea level.

Artisans beginning around 900 B.C. carved life-size jade masks that almost look like molded plastic, but which must have been the result of a laborious process to grind and polish this extremely hard, dense stone.

All Olmec sculpture was created for a purpose, whether it be religious or political. In the case of Monument 9, it clearly pertains to the Earth, which in Mesoamerica was considered a sacred, living being.

The Olmecs existed at a time when maize agriculture had first developed, which stabilized and increased their economy—a transformative shift in the development of Mesoamerican civilization.

During this period, they developed an elaborate religious system that emphasized the sacredness of corn and rain, including a maize god. Quite frequently, this deity is depicted with an ear of corn emerging out of the center of his cleft head. In other cases, the head is sharply turned back, invoking growing corn. This form appears in Teopantecuantitlán, an archaeological site in highland Mexico, where there is a masonry court with four images of the Olmec maize god.

As a tall grass, corn needs a great deal of water to survive the summer, making rain all-important. Trying to please the rain god in return for rain was a vital part of Olmec religion.

The Olmec spread similar practices and beliefs across ancient Mexico and Guatemala, probably in part to engage other peoples more directly with their economic trade network. Rather than an empire of domination, the Olmec were a culture focused on agricultural abundance and wealth.

Sacred mountains were of extreme importance as well, as can be seen at Chalcatzingo and at a hill called Cerro El Manatí, located very close to the site at San Lorenzo. At this hill, there is a perennial spring with sweet freshwater that fills a pool below at the base. In this pool, the Olmec offered a huge amount of valued material, including rubber balls for ritual sport, as well as many jadeite axes. According to two scholars of Mesoamerica, Ponciano Ortiz and María del Carmen Rodríguez, this is the first clear example of a sacred mountain of abundance, which persists in Mesoamerican belief and ritual to this day.

Far to the west of the Olmec heartland, in the Mexican state of Morelos, is Cerro Chalcatzingo, the site where the Earth Monster monument originated. Here, the Olmec focus on the mountain as a provider of wealth and sustenance, portrayed in several sculptures as a cave.

Even before Olmec times, the idea of fertile caves was shown as a four-lobed motif resembling a flower – an important symbol that continued even into the 16th century with the Aztec.

The most famous Olmec bedrock carving at Chalcatzingo is called Monument 1 and features a woman in profile—probably a goddess—seated within the cave. This carving is directly above where rainwater pours down from the top of the mountain. Below are what archaeologists call “cupules”: cuplike holes carved in bedrock directly below to receive this water, and collected by priests and pilgrims. On the opposite side of the hill is another rock carving featuring the same cave in profile, facing Monument 1.

Sadly, Monument 9, which was recently returned to Mexico, was looted from the site, so its original context is unknown. In archaeology, it is important to understand not only when an object was made and who created it, but where it was placed. Nonetheless, Monument 9 portrays the same cave as two other sculptures at the site, which are carved directly into the rock surface of the mountain.

Monument 9 is significant, as it denotes the central Earth Monster cave, and unlike the other two Olmec carvings, it is face-on rather than rendered in profile. It probably was placed against a mound with its open mouth leading to a chamber inside, symbolizing a portal to the underworld.

That this highly sacred object is back in Mexico is of utmost importance for Indigenous Mexicans. To its creators, Monument 9 likely represented the source of life and abundance, as well as sacred rituals associated with them—ideas and practices that pervaded subsequent Mesoamerican civilizations.

Karl Taube is Distinguished Professor of Anthropology at University of California, Riverside.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook