Raising Orange Peels to an Art Form, One Fruit at a Time

The artist Yoshihiro Okada uses only whole, unbroken peels.

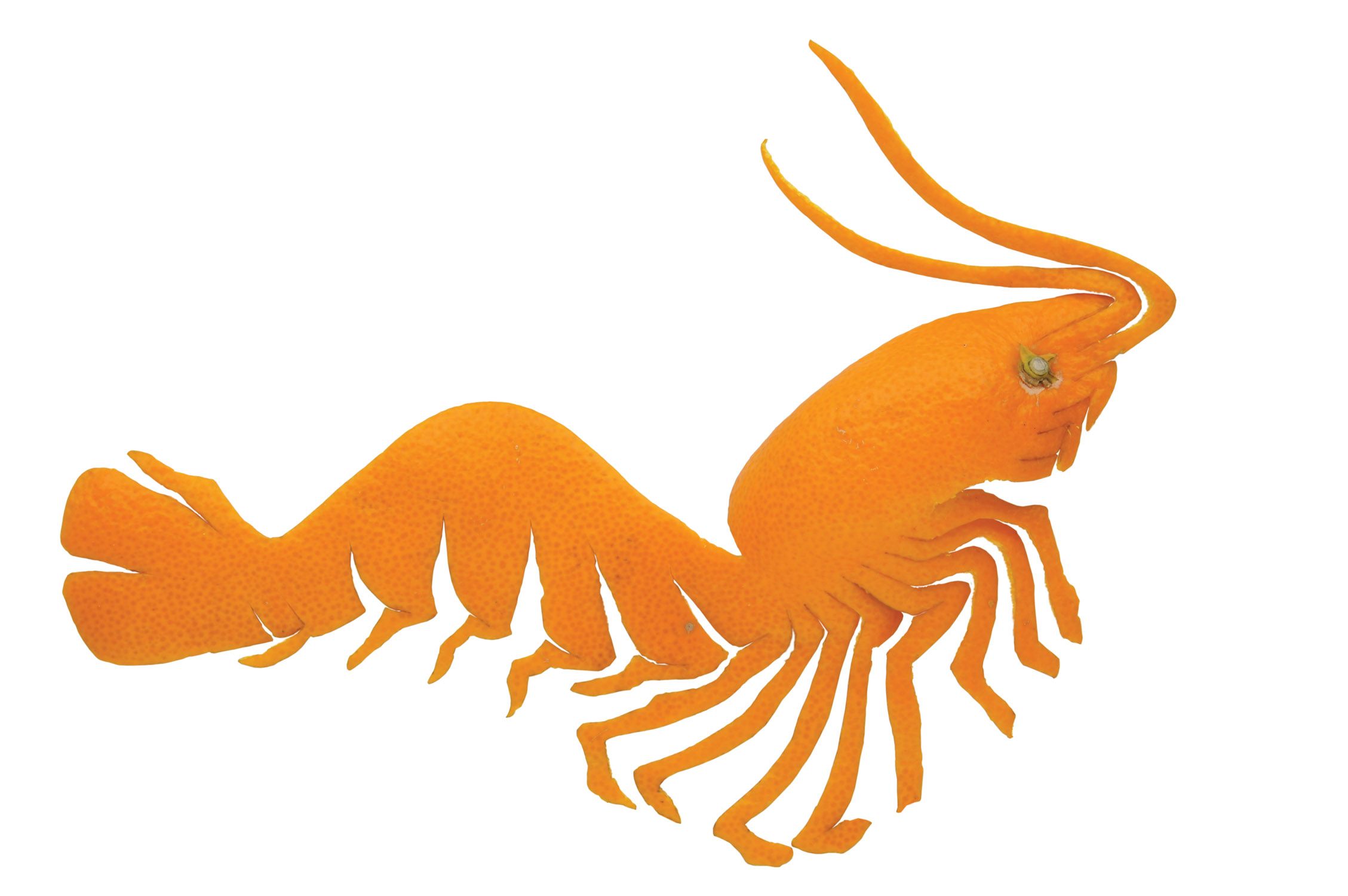

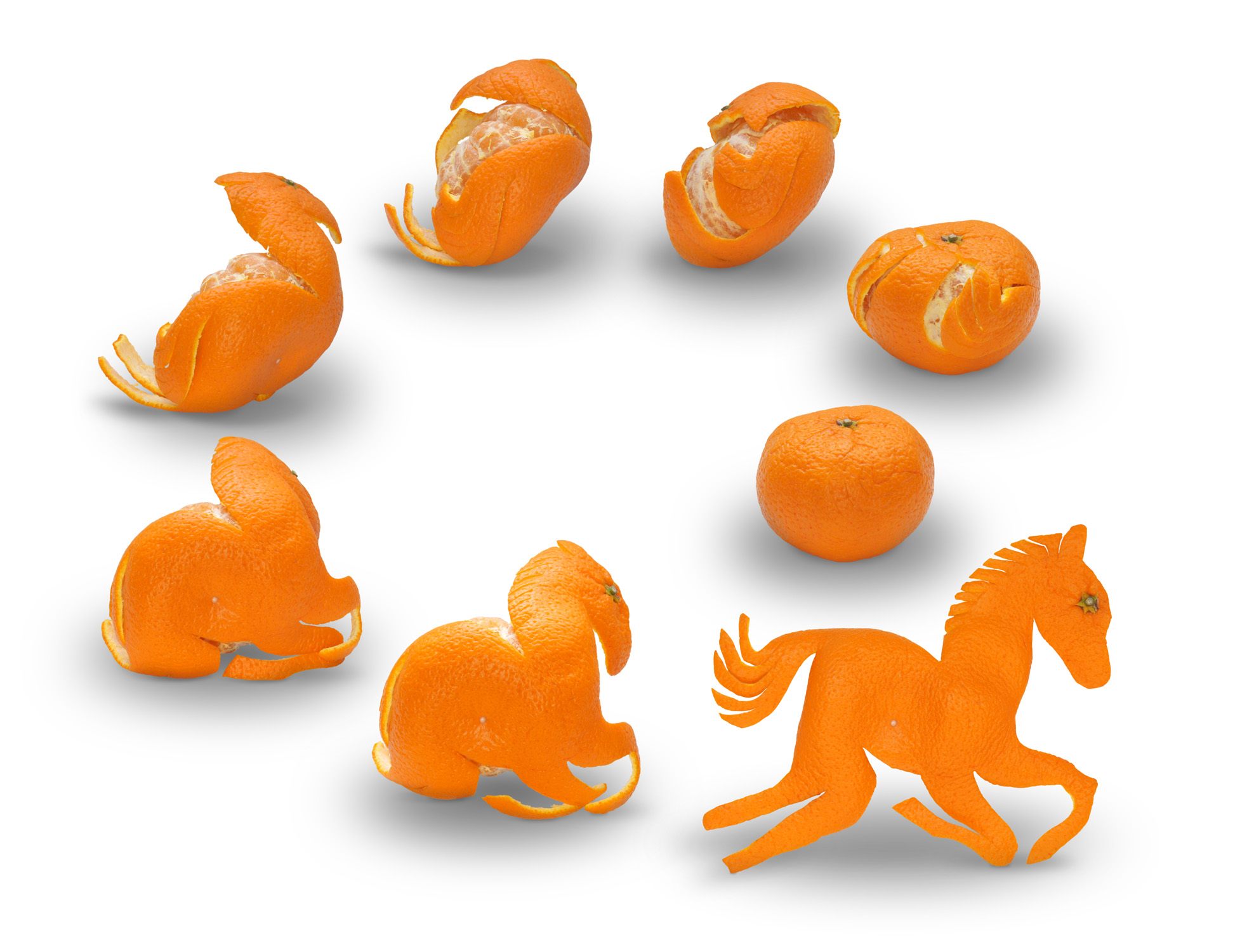

Yoshihiro Okada saw the design of a prawn in a vision. He saw it clearly: Out of a tangerine peel, the crustacean emerged, unfurling its many thin legs, the articulated length of its body, the fan of its tail. Near the eye—the stubby end of the tangerine stem—the prawn waved long antennae that reached out to sense the world around.

After the vision, Okada picked up a tangerine and tried to execute what he had seen. He can peel freehand, but for a design like this, with such delicate features, it helped to use a knife. It came out the way he’d envisioned it on the first try. He was amazed. “The shrimp design is one of the most sophisticated designs among all of my works,” he says.

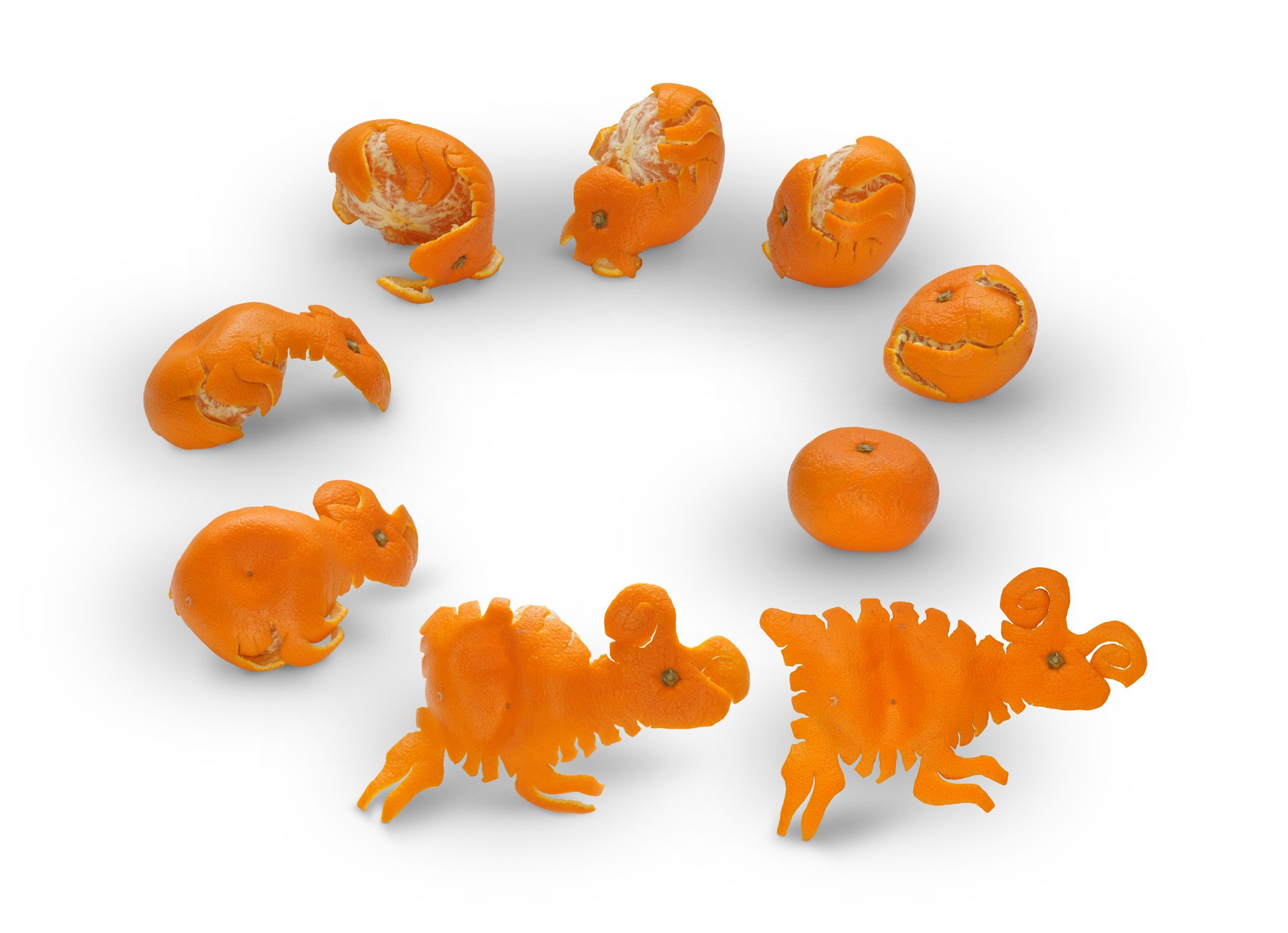

Okada is an unusual artist. His medium is the thin peel of a citrus fruit, which he unwinds into a variety of elegant shapes, most depicting animals from land, sky, and sea. He operates according to a principle of conservation. Each shape must use the entire peel; no part can be removed and nothing can be added. Within this limitation, he has created more than 170 designs. “I am sure that I will be able to make almost any kind of animal or bird if I am asked to,” he says. Now he is working on series of symbols—the Juni-shi zodiac, popular in Japan; the Western zodiac; the symbols of the twelve tribes of Israel.

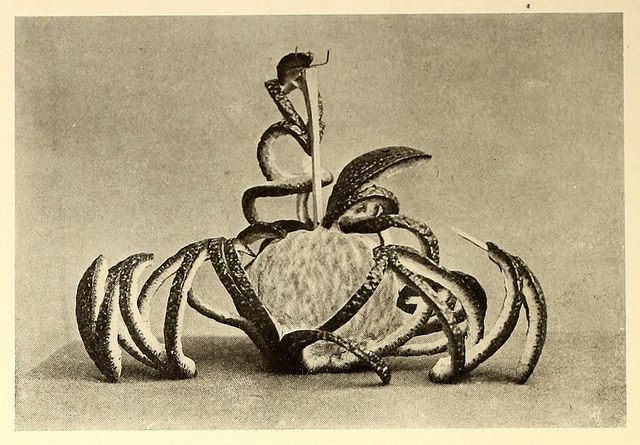

There are a few others in Japan who have pursued the art of peeling citrus fruit, but Okada’s designs are the most sophisticated and varied among them. It is rare for a person to dedicate themselves with such care to coaxing designs from citrus. Okada may be the first master peeler in a century, since a British magazine found a “champion orange peeler” in 1899, a ship’s cook identified only as Mr. Birch, who had created his own vision of ornamental orange art.

In 1899, when The Strand Magazine, a British monthly, introduced its readers to Birch, reporter A.B. Henn described his subject as “the one man we would wish to have as a companion on a desert island of the Pacific.” In a photo, Birch’s hair is neatly parted and his mustache carefully trimmed. He’s wearing an apron and holds a partially peeled orange in his hands. According to the article, Birch was a tinkerer and inventor who could make utensils (including an egg separator) from coconuts, and a very good cook besides—“one of those extraordinary all-round men it is one’s luck to meet with but seldom.”

On his voyages around the world, Birch happened to be holed up with oranges, thousands upon thousands of cases of oranges. By the 1890s, the citrus industry was booming and worldwide trade in oranges was growing. Birch took the opportunity to apply his artistry and industry to his juicy traveling companions.

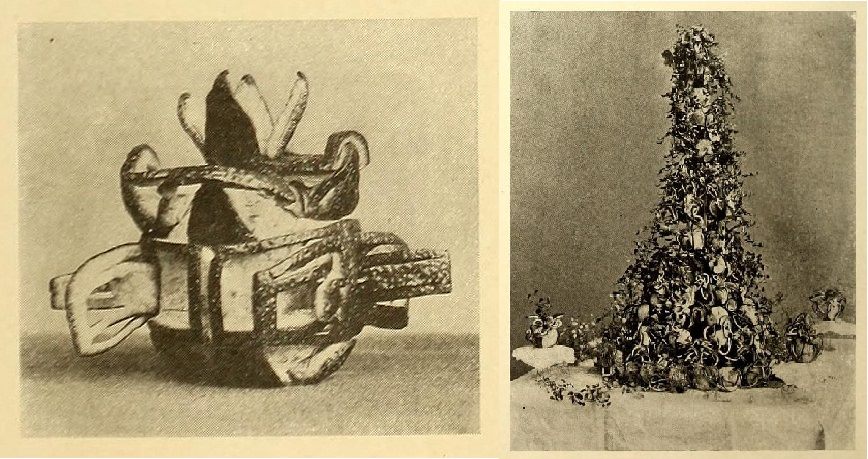

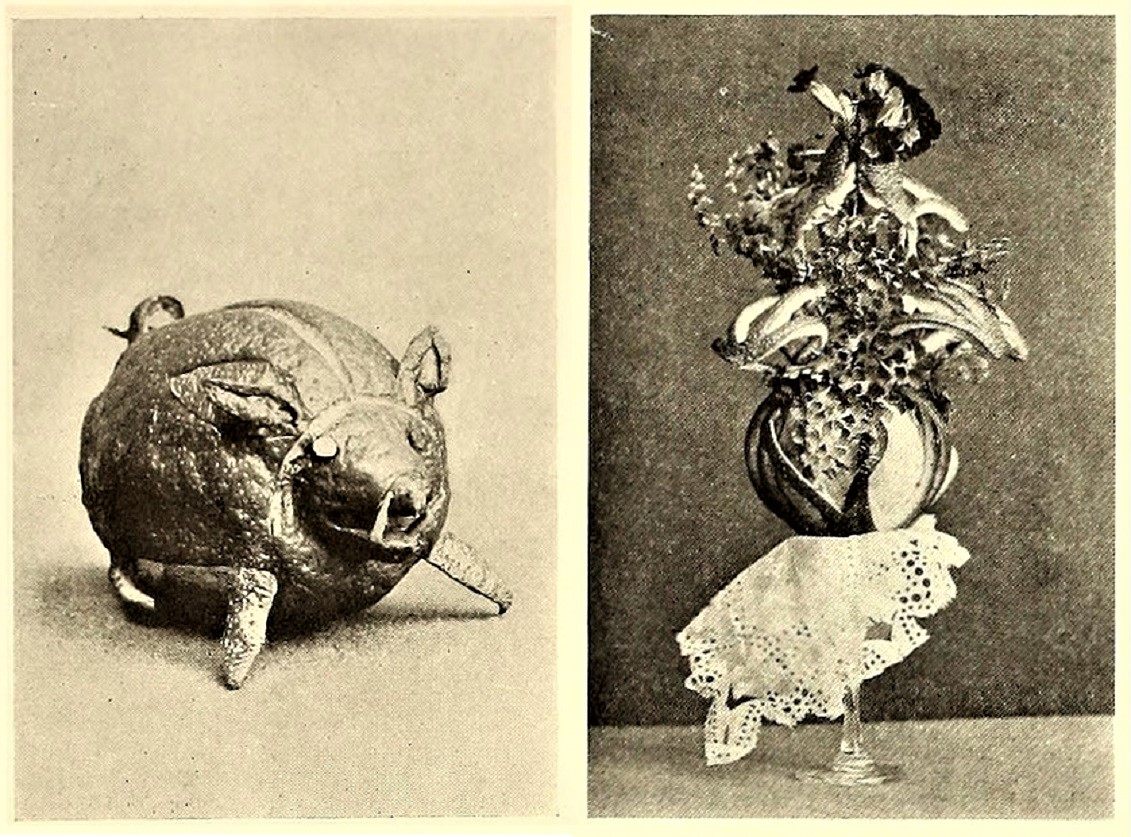

He developed a technique of quartering the peel and then slicing each quarter into a series of attached, ribbon-like strips. Loosened in this way, the fruit’s outer protection could be crafted into all manner of designs. Birch wove the rind into abstract, flower-like decorations that soared away from the fruit. Some of his designs show a sense of humor: He created a man’s face that looked like it might have come from an Cubist painting and a cute little boar complete with ears, tail, and tusk. He also created an Japanese houseboat and a British crown in delicate detail. His pièce de résistance was a pile of ornately peeled oranges, gathered into a towering centerpiece of tangled, twining fruit peel. (It must have smelled amazing.)

There’s little evidence of what happened to Birch. Outside of the Strand article, he doesn’t seem to have appeared in any other contemporary media. In 1910, American Homes and Gardens published the same images that had appeared in Strand, along with instructions on ornamental orange peeling. But Birch had disappeared from the story. As ephemeral as his art was, it outlasted him.

Okada has seen the photos of Birch’s art, and he finds it beautiful, if distinct from his own work. “My art and that art belong to a different kind of art,” he says, and compares Birch’s style to that of a different, current peel artist whose work also features curling strips.

To Okada, the key to his own orange-peeling art is the self-imposed stricture that requires the whole peel to be used in every design. “One of the key words which characterizes this art is compromise,” he says. For his rabbit design, for instance, the section of peel that becomes the rabbit’s tail is wedged between the part that becomes its two ears. If the tail is enlarged, the ears shrink. “Once one part is changed, the other part is changed also,” he says. “The designs always come back to one round sphere. So in that sense, they are inevitable designs.”

Okada discovered the art of orange peeling when he once peeled a tangerine and noticed that it had come out, roughly, in the shape of a scorpion. Earlier in life he had trained as an artist, and the visual problem of the scorpion peel absorbed him. For two weeks he worked to perfect the design—30 minutes each day, peeling fruit after fruit. After hours of trial and error, he accomplished his goal, to the extent that he could. There seemed to be no possibility of more progress. What he had was what could be. “I compromised with that shape,” he explains.

That was in 2006. Today, it often takes him less time to create a new design, as one animal shape evolves into the next. He starts with two tangerines with the same design drawn on their skin. He peels one and uses that shape to guide his revisions on the second. He moves on to the second one. He peels. He compares. He repeats.

“It takes a lot of oranges,” he says.

A new design can still present challenges. In his series of symbols representing the tribes of Israel, he struggled with the one for Simeon, whose symbol is a sword. The long, thin blade left too much peel unused. He tried to solve the problem by making the blade wide, but that only distorted the sword’s shape.

At the time he was also working on a symbol for the Levites, which he chose to represent in Hebrew letters spelling out the name. That solution inspired him: He could incorporate the Hebrew letters of Simeon’s name into the sword. Finally it came together.

Okada is also a pastor of a Christian church. When asked if there’s any connection between his art and his work with the church, he says that the art of orange peeling can demonstrate how the instructions of the Bible can give life meaning. “If the tangerine is peeled at random, the result is random shape,” he says. “But if it is peeled according to the instruction, an amazingly wonderful art is born.”

Okada, now 51, has published books of his designs and tried to spread the word about the practice he has developed. He’s taught classes on the art of orange peeling and would like to publish a book in the United States if he can. But ornamental orange peeling never really caught on in England or America, and in Japan it is more popular but still rather obscure. It may take another century before the next great orange artist comes along.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook