Climate Change May Have Helped Spread a Language Family Across Australia

When food and water were in short supply, people moved, taking their languages with them.

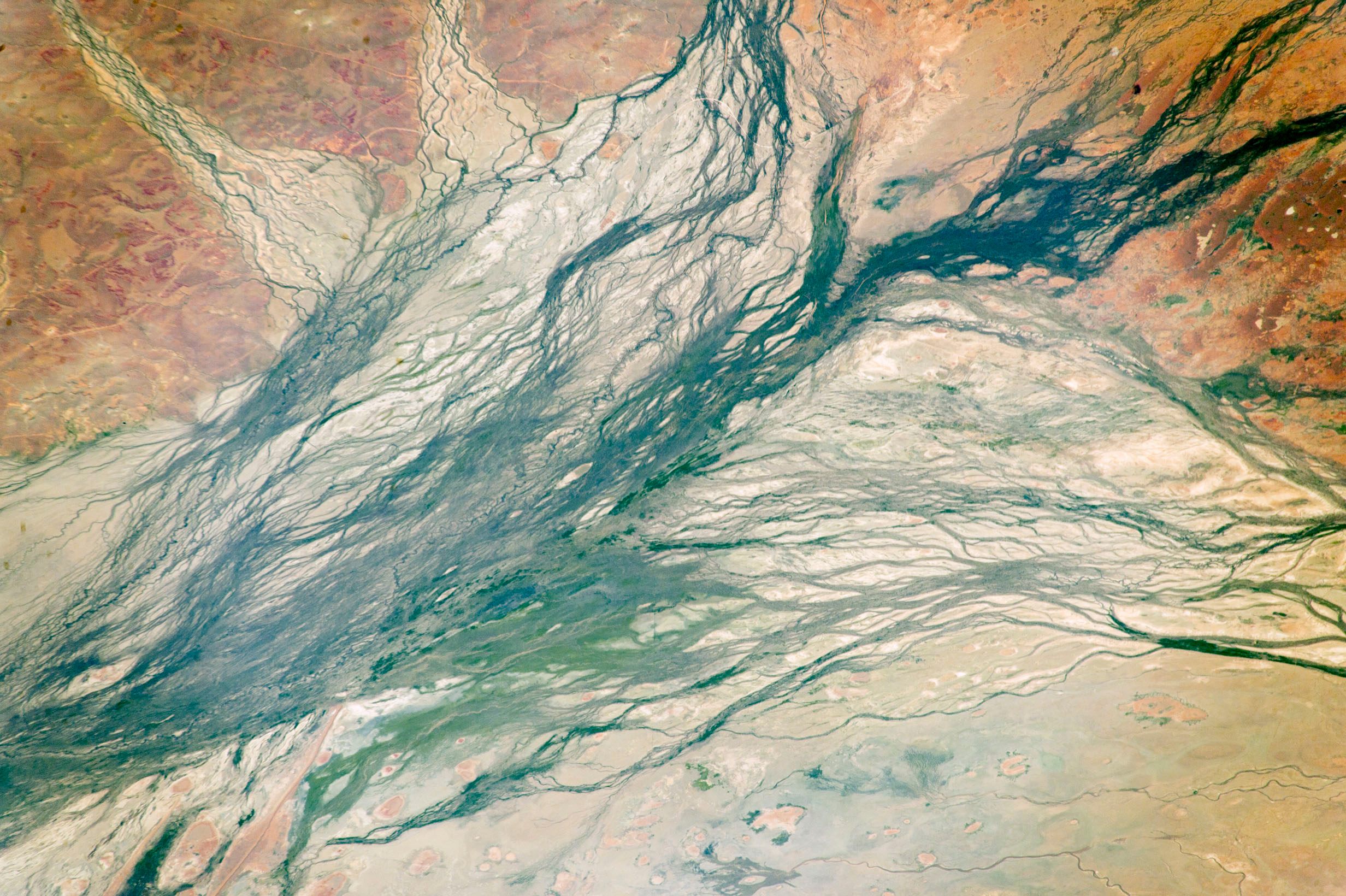

On the map of Australia’s indigenous language types, Pama-Nyungan languages stretch expansively across the country, dipping down into the hollows of Western Australia and Victoria, and reaching high up into the furthest cranny of Queensland, to the north-east. In the remaining 10 percent of the country, languages based on Australia’s other 26 Aboriginal language families jostle for space in a cluster around the Northern Territory.

It’s extraordinary that there are 27 different Aboriginal language families at all—in Europe, by contrast, there are just four—but still more incredible that Pama-Nyungan should have such dominion across so much of Australia. For decades, linguists have puzzled over this problem: Where did the ancestral Pama–Nyungan language originate, and when? And why did it make its way across 90 percent of the country? Researchers at Yale University now believe they may have the answer, with their results published this week in Nature Ecology and Evolution.

Researchers compared changes in 200 words from 306 different Pama-Nyungan languages, allowing them to build a “tree” of languages. (The computer model they used, co-author Claire Bowern wrote in an article on The Conversation, is “adapted from those used originally to trace virus outbreaks.”) The models don’t just show how words are related to one another, but how long they might have taken to change. This, in turn, helps to reveal an estimated age of the language family. The models pointed researchers to what is now the tiny, isolated settlement of Burketown, Queensland. It has a population of just over 200 people, and a turbulent history of disease, storm devastation, and the massacre of many Aboriginal residents in 1868.

According to the model, the proto-Pama-Nyungan language likely appeared just under 6,000 years ago. But why did the language family travel thousands of miles south, from Queensland down to Western Australia and Victoria? Bowern cited a theory which posits that around the same time, “increasingly unstable conditions caused groups of people to fragment and spread.” The model supports that theory: In short, changes in climate affected food and water sources. When there was plenty, people stayed, and populations increased. But when there was a shortage, they moved, taking their languages with them.

“Because languages change regularly, we can use information in them to work out who groups were talking to in the past, where they lived, who they are related to, and where they’ve moved,” Bowern wrote. Though there is little written record of Aboriginal history, there is history hidden in the words of these languages themselves, revealing the stories of their original speakers.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook