Before Food Trucks, Americans Ate ‘Night Lunch’ From Beautiful Wagons

They were the ancestors of the modern diner.

In 1893, Boston was bustling, especially after the sun went down. “Night owls of all classes” roamed the streets, wrote the Boston Daily Globe, including “workers, idlers, pleasure seekers, spendthrifts, tramps and bums.” At some point, all of these people would want something to eat. The wealthy could get their quail on toast at any hour, observed the writer. For everyone else, there were the night lunch wagons. While they served inexpensive eats, the wagons themselves could be as fancifully decorated as music boxes on wheels.

Though night lunch wagons would eventually be gilded, they had humble origins. According to Richard J.S. Gutman, a diner expert and author of the classic American Diner: Then and Now, it all started with a man with a basket. Walter Scott was a street vendor who sold sandwiches and coffee in Providence, Rhode Island, first from a basket and later from a pushcart. Business was good, so in 1872, he set up shop in a wagon outside a local newspaper office. Scott was a pressman himself, so he knew that journalists wanted quick meals at strange hours.

It wasn’t just journalists who stayed up late, though. Night shift workers wanted a meal when they punched out, and party-goers wanted grub when they emerged from the bar. But most restaurants closed at 8 p.m. Scott’s innovation—serving sandwiches, pie, and coffee from a horse-drawn wagon as a “night lunch”—soon spread. In 1884, Gutman says, a cousin of an imitator of Scott’s moved to Worcester, Massachusetts, and made the first lunch wagons that customers could sit inside.

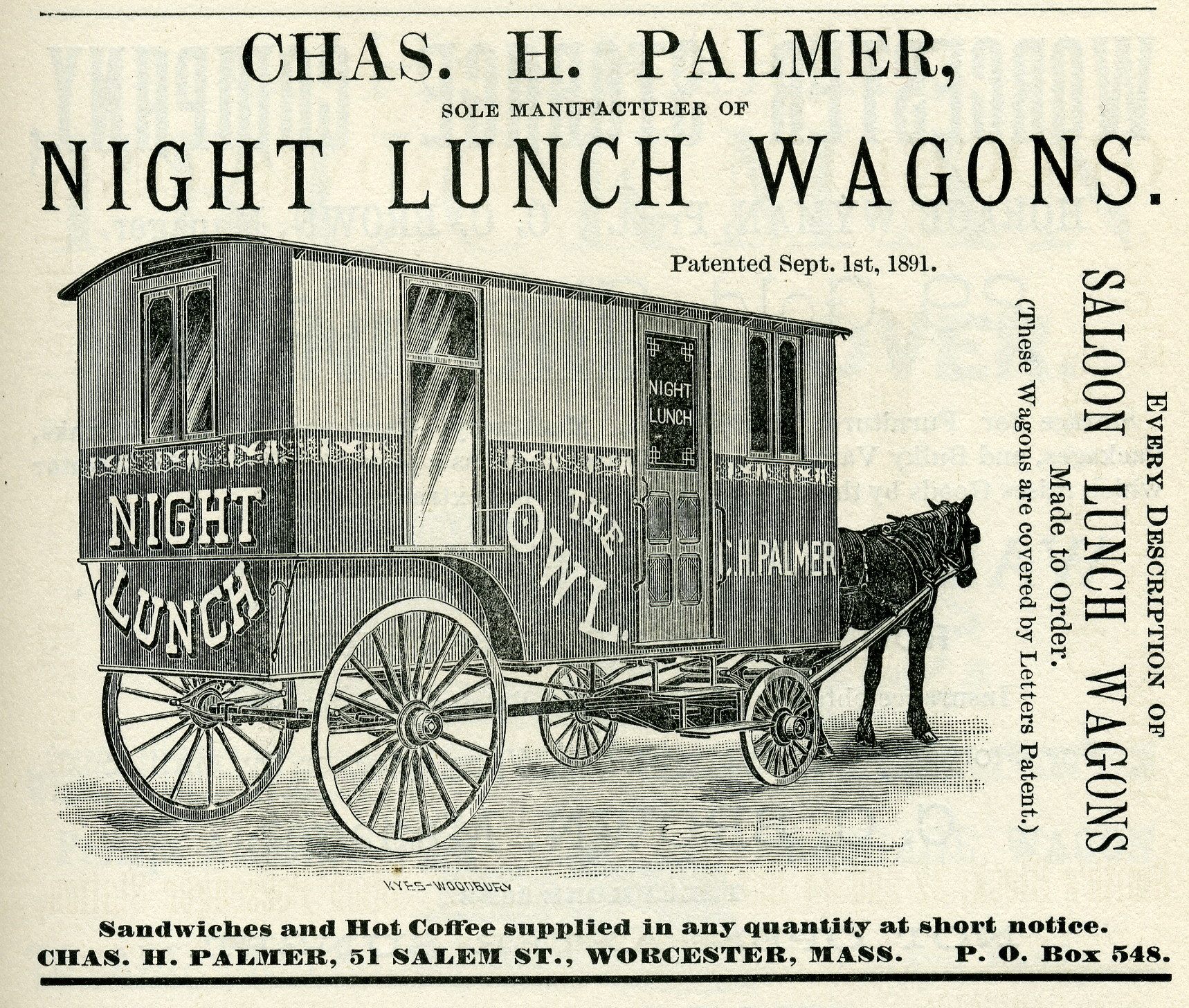

Worcester soon became the nation’s lunch-wagon producing capital. Businessmen such as Charles H. Palmer and Thomas H. Buckley received patents and built factories to turn out lunch wagons, and shipped them across the country. While Scott’s original wagon was a renovated freight wagon, lunch-wagon makers began to design aesthetically pleasing vehicles. Etched-glass windows and colorful exteriors beckoned eaters inside, and the interiors were “painted up with fleur de lys and amazing murals” that echoed the work of old Dutch masters. Gutman, who studied architecture, notes that lunch wagon designs mirrored trends in commercial architecture at the time.

According to the Cincinnati Enquirer, the first such-decorated wagon that rolled onto the streets of Worcester caused a sensation. When another debuted in Ogdensburg, New York, people gathered to stare open-mouthed at its “Aladdin-like” interior. The Enquirer described the popular wagon style as having elegant carvings, skilled paintwork, and amenities such as sinks for washing dishes. Proprietors typically stood behind small counters, heating food on grills and dispensing coffee from elaborate urns to patrons inside and out. The average size of the wagons was eight by 14 feet. Buckley’s wagons were particularly sensational. “They were described as perfect little palaces,” says Gutman.

Despite the needling of the Boston Daily Globe, night lunch was for everyone. A typical night would see “people in tuxedos, businessmen, along with the ordinary worker and the showgirl,” says Gutman. In the early days, menus were simple: sandwiches filled with ham, chicken, or cheese, apple and mince pies, and coffee. Adding a grill expanded some lunch wagons’ offerings, but the food remained hearty and simple: a contrast to the positively rococo interior design.

But according to Gutman, their elaborateness may have contributed to their downfall. “Certainly in the beginning, they looked fabulous,” he says. But the wear-and-tear of nightly traffic wore away the paintwork, and some business owners couldn’t afford upkeep. Many successful lunch wagon businesses eventually became stationary establishments, and former wagon manufacturers followed suit, resulting in what would eventually be known as diners. The remaining horse-drawn lunch wagons became increasingly shabby and downmarket, not to mention in the way of automobiles. Much like the food trucks of today, restaurants lobbied against them, and as early as 1909, lunch wagons began to be banned from city streets.

Still, one wagon managed to survive and remain in operation to this day.

Not everyone was ready to let go of the horse-drawn past. Namely, Henry Ford of automobile-producing fame had a soft spot for a particular lunch wagon. According to The Henry Ford curator Donna Braden, the Owl Night Lunch Wagon rolled the streets of Detroit when Ford was a young, hungry engineer. Years later, in 1926, Detroit banned night lunch wagons with a city ordinance. So Ford snatched it up and later installed it at Greenfield Village, an outdoor history complex that is part of The Henry Ford museum in Dearborn, Michigan.

For many years, the Owl Night Lunch Wagon was the only spot to buy food in Greenfield Village’s sprawling grounds. Boxy and white, it was a pale shadow of lunch wagons past.

But in the 1980s, Gutman contacted The Henry Ford and told them that they had the last horse-drawn lunch wagon left. He also pitched them on restoring it to glory. “He showed us lots and lots of pictures of typical lunch wagons of that era,” says Braden. The Henry Ford ultimately brought Gutman on board for the renovation of the Owl Night Lunch Wagon.

From its stripped-down state, the Owl Night Lunch Wagon was transformed. Gigantic red-and-blue letters now decorate the sides, and etched-glass windows show owls perching atop of crescent moons, an ode to the night-time eateries of the past. While diners once sat and ate inside the Owl Night Lunch Wagon, these days servers hand period-appropriate frankfurters out the window. “This wagon is the real thing,” Gutman says of the rebuilt and renovated eatery.

Despite the restored pomp of the Owl Night Lunch Wagon, Gutman speaks longingly of even more lavish lunch wagons, whose glitter now exists only in photographs. Gutman hopes to one day unearth a better-preserved example, with its paintings relatively intact. “That is what I’m looking for, to find some buried lunch wagon,” he says. While diners are the direct descendants of lunch wagons, and food trucks still roam cities today, their designs speak more to Guy Fieri than the Gilded Age.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook