How Gruesome Penny Dreadfuls Got Victorian Children Reading

Despite causing a moral panic, these salacious tales helped boost literacy in Victorian England.

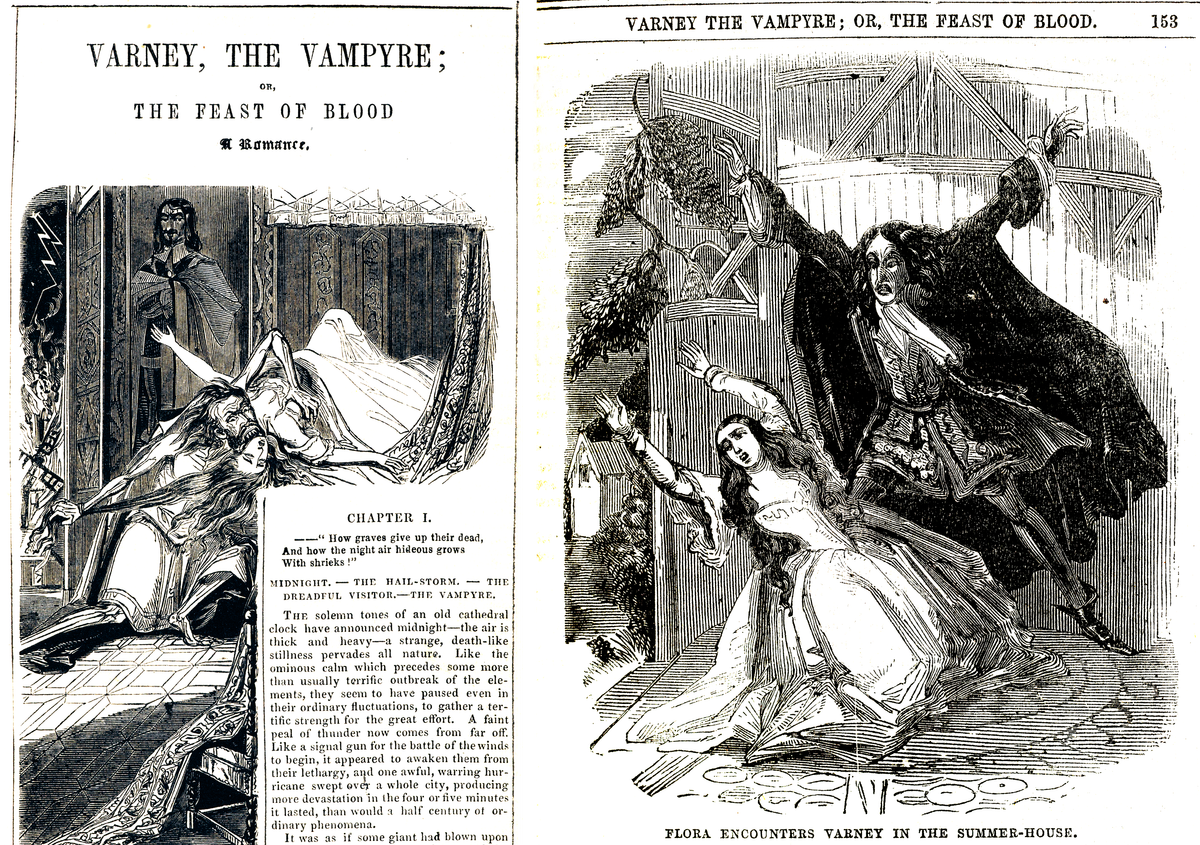

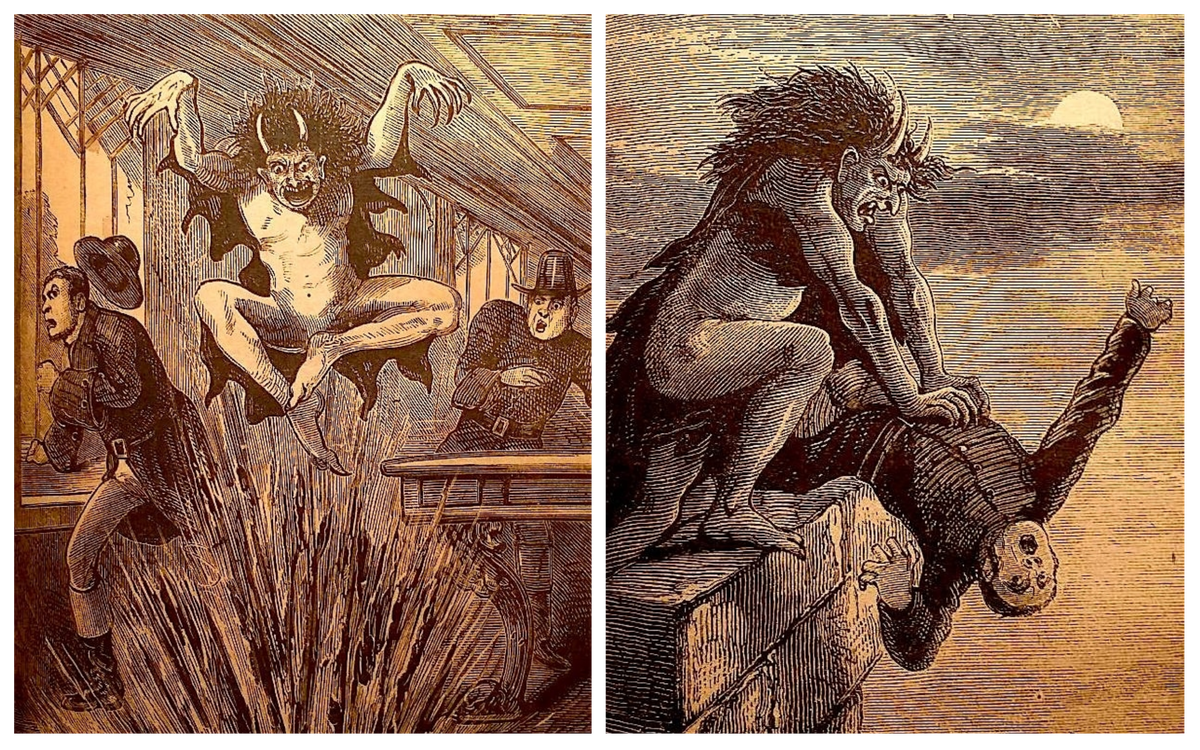

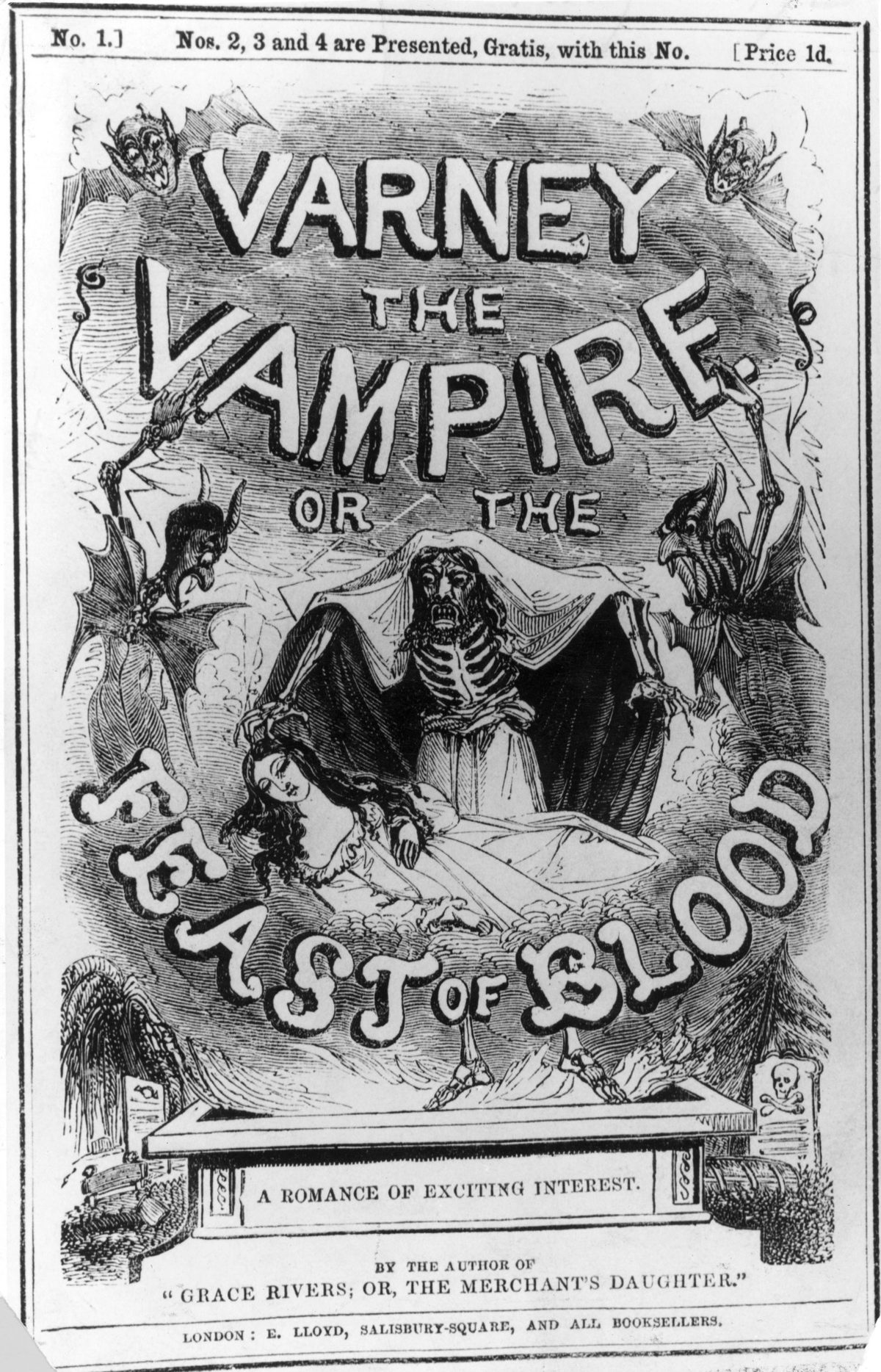

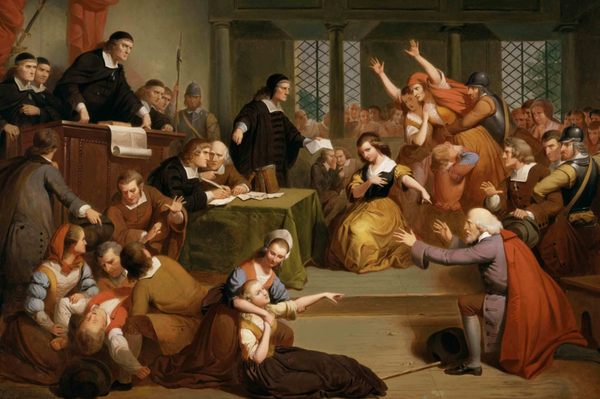

A crash of thunder jolts a beautiful girl awake. She sits bolt upright in bed, her eyes transfixed on a storm outside. Lightning, and for an instant, a tall, gaunt figure is illuminated outside. “What—what was it? Real, or a delusion?” she gasps, melodramatically. The figure scrapes its long nails across the window—definitely not a delusion. “Help!” she cries, but there is no one to come to the rescue. In a sudden rush the figure is in the room and has dragged the girl by her hair to the edge of the bed, where it plunges its teeth into her neck: “a gush of blood, and a hideous sucking noise follows. The girl has swooned, and the vampyre is at his hideous repast!” Not exactly children’s literature, is it?

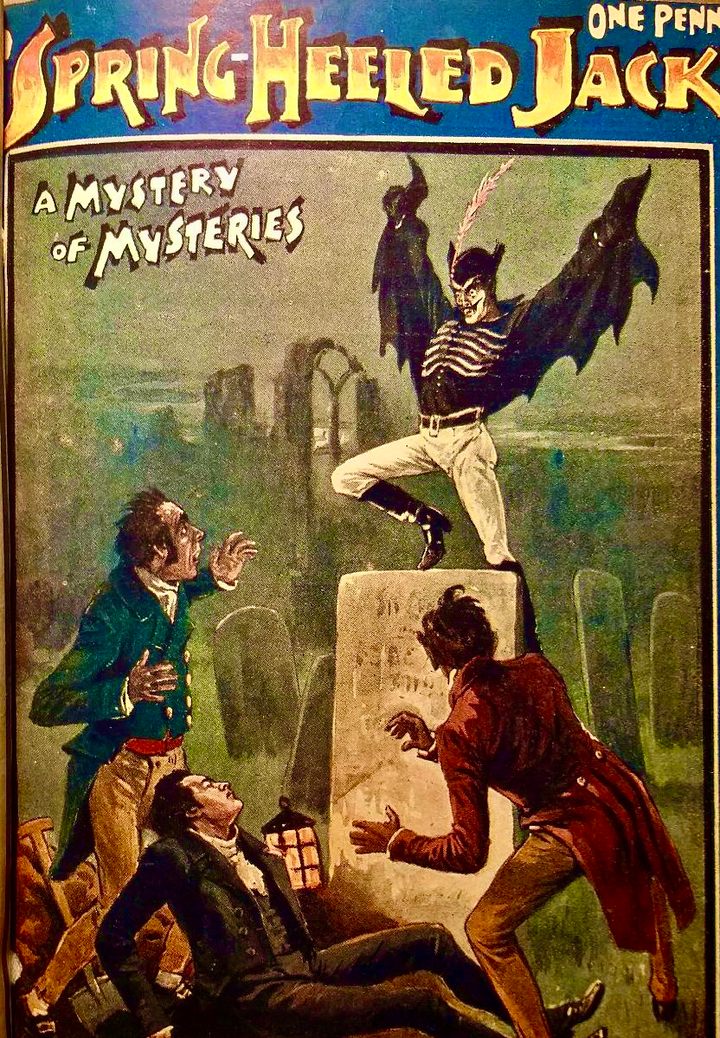

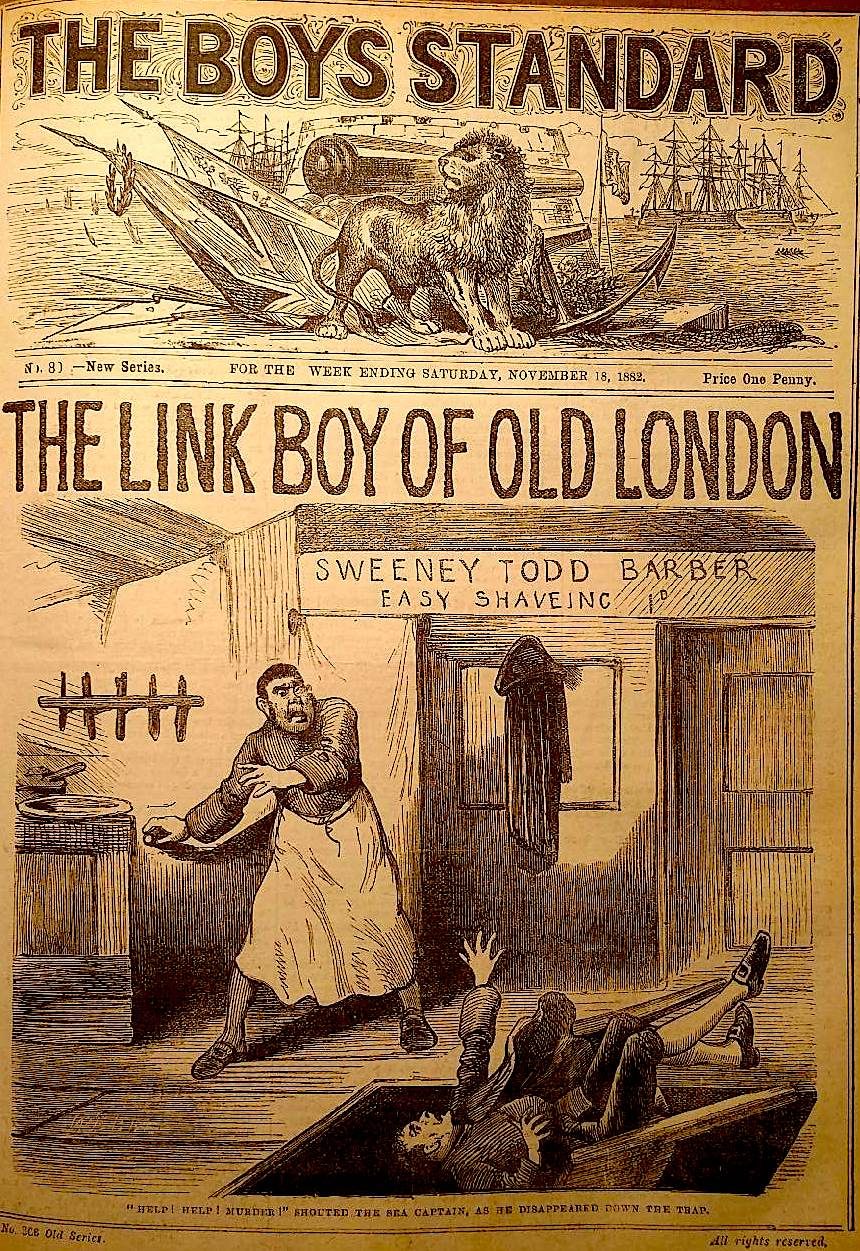

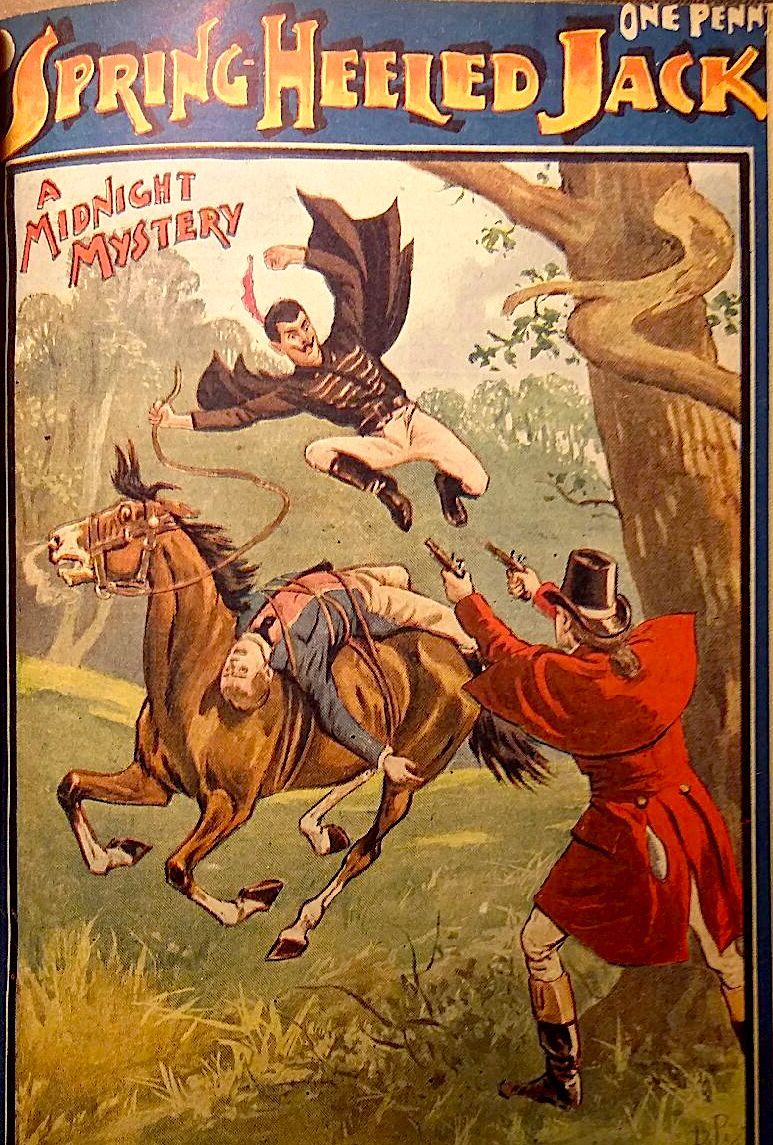

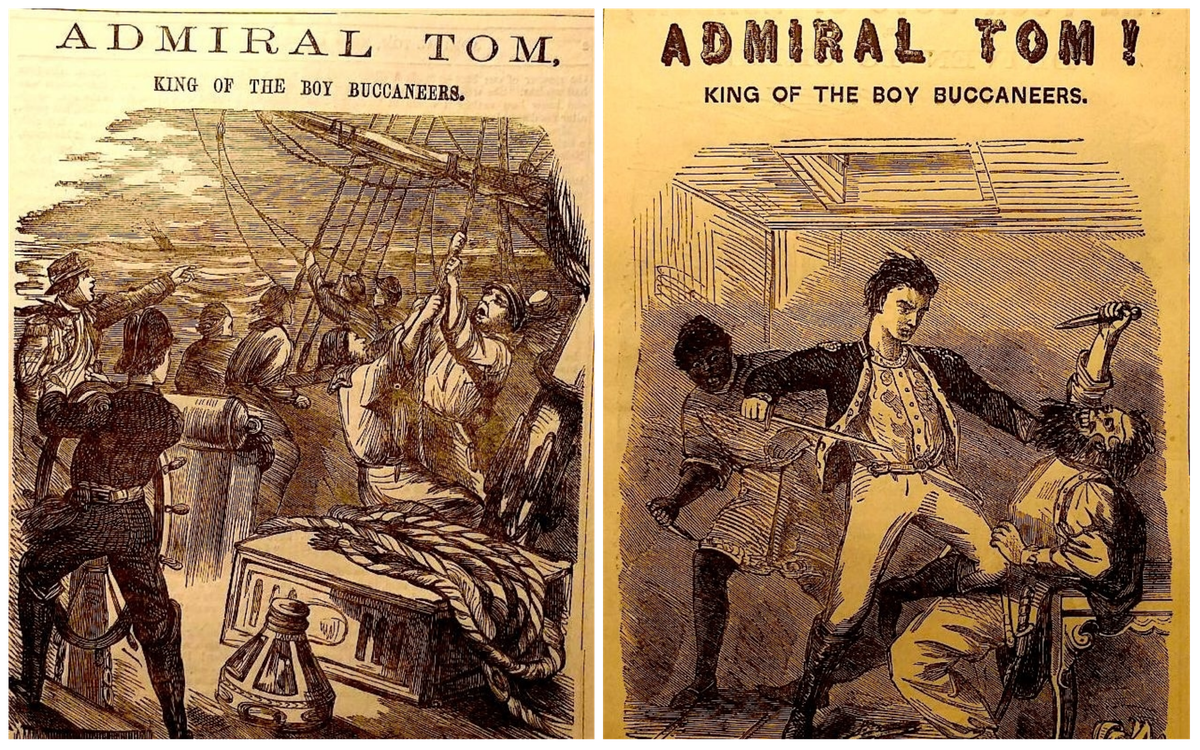

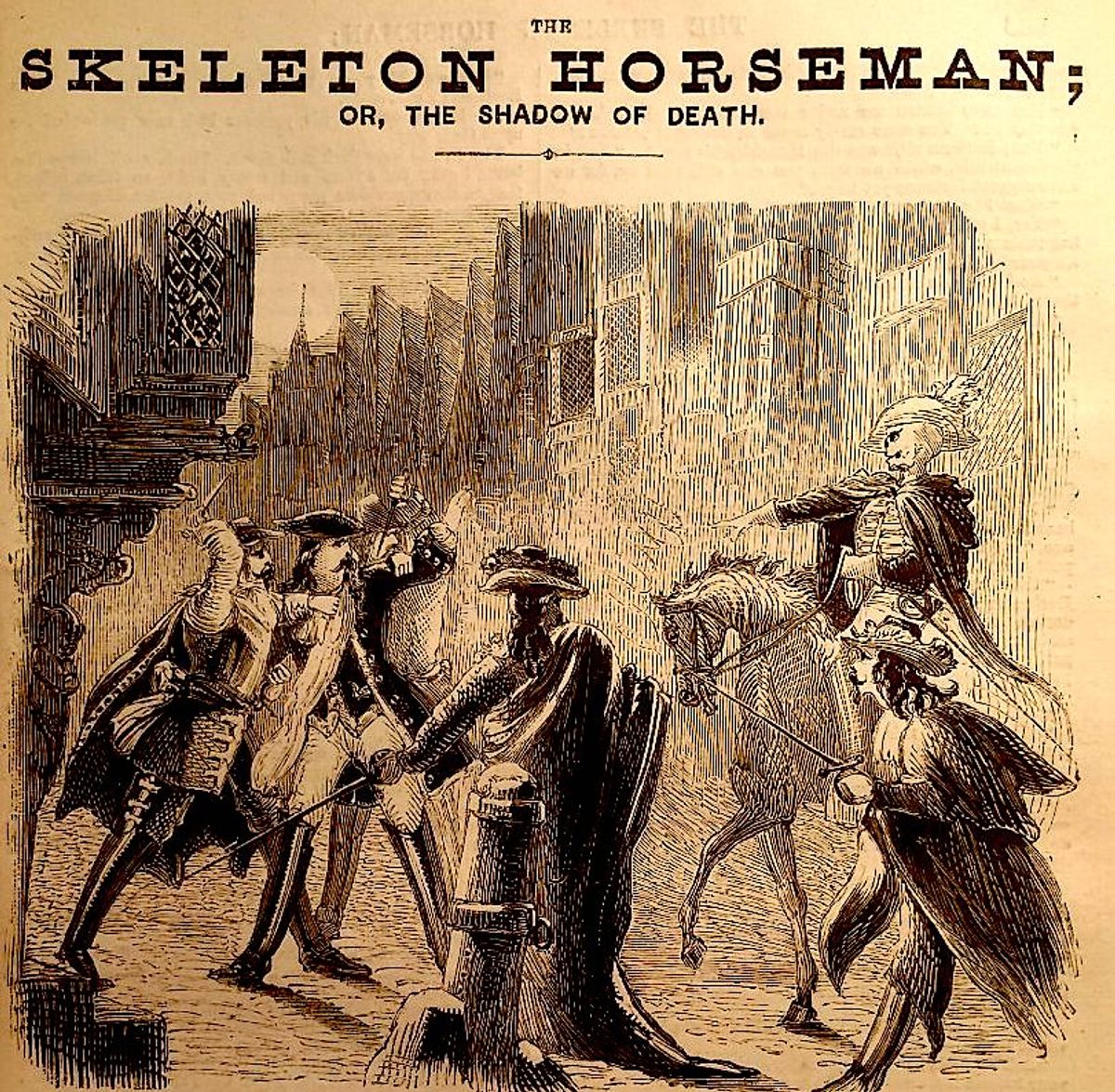

So begins the gruesome tale of Varney, the Vampire; or, the Feast of Blood. First published in 1845, it was one of the most popular stories of its time. Readers could buy serialized installments of stories like these, in pamphlets of a dozen pages or so for just a penny. It’s how they got the name we still know them by today: penny dreadfuls.

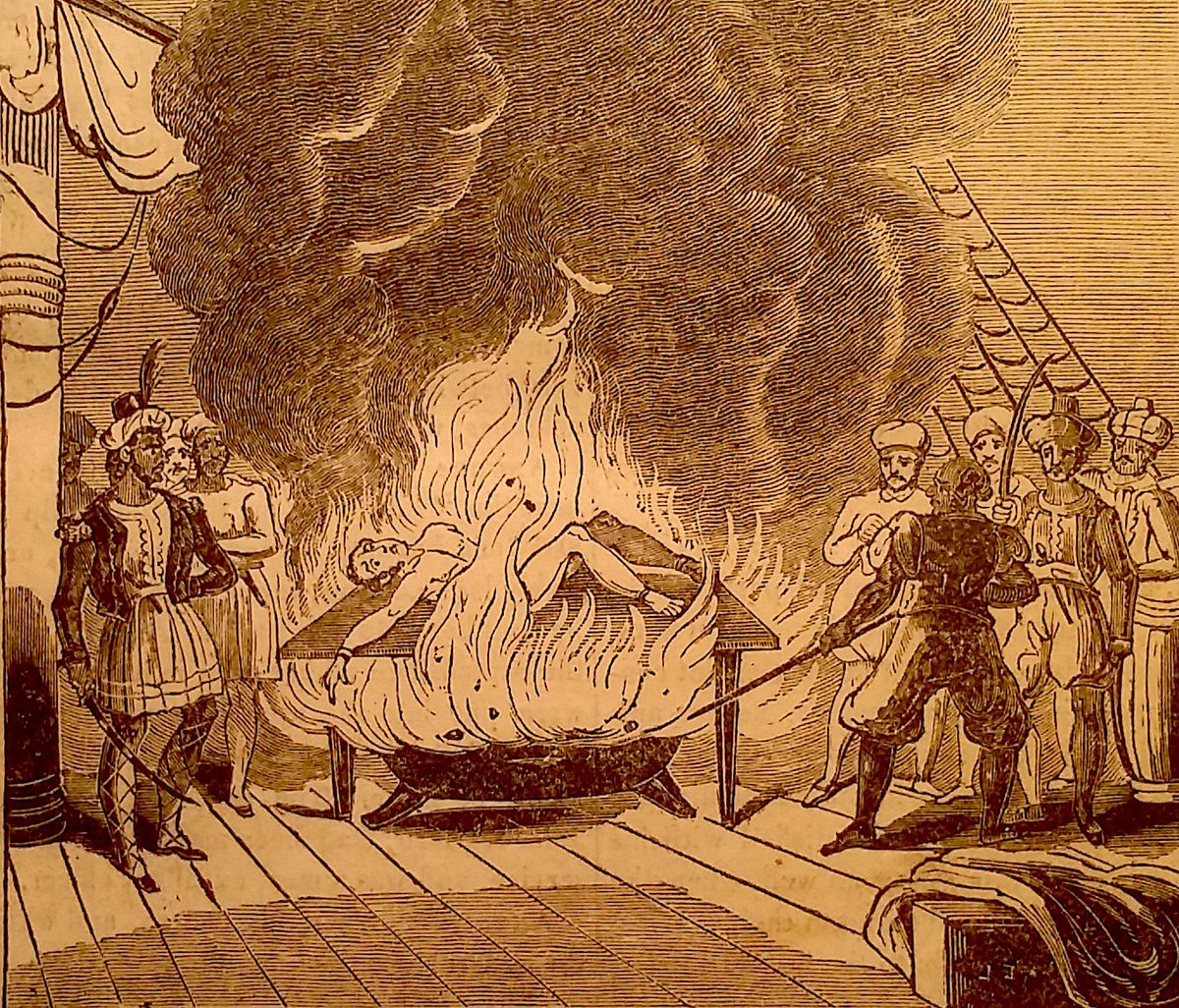

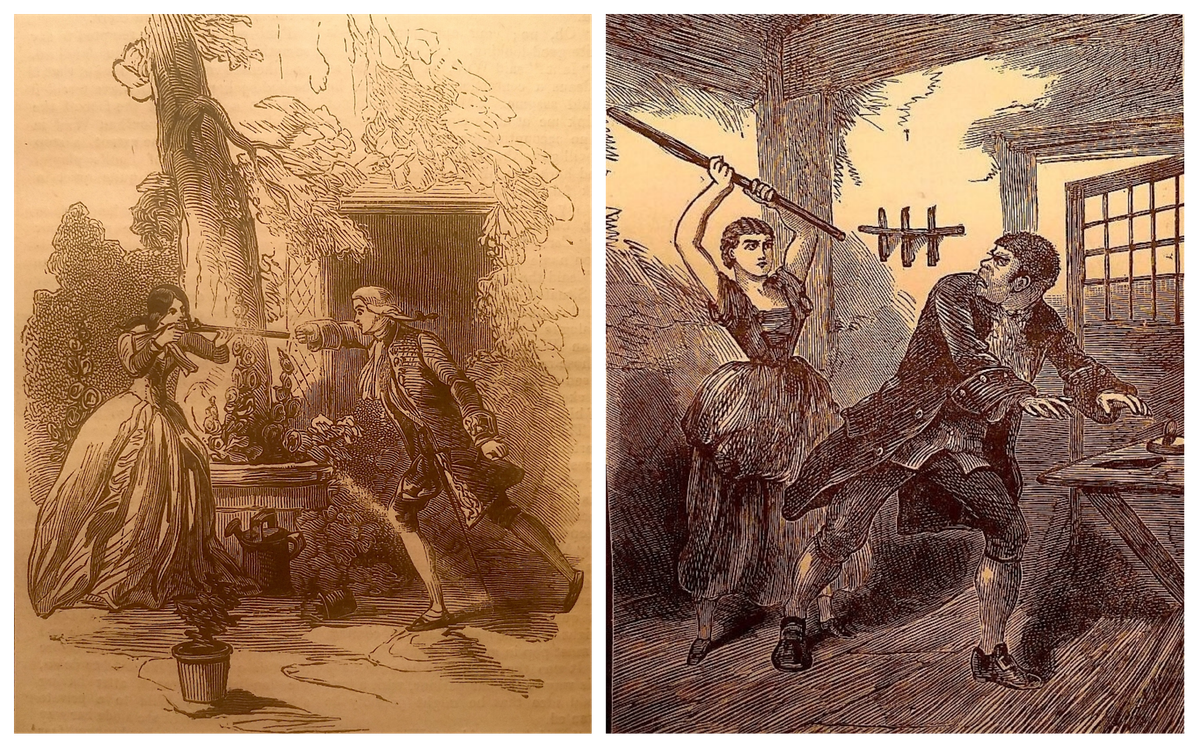

Characters from these stories, such as Varney, Sweeney Todd, and Spring-Heeled Jack terrorized the Victorian, English-speaking public from England to the United States to Australia. Author, journalist, and sometimes apprentice of Charles Dickens, George Augustus Sala wrote in 1861 that penny dreadfuls are “a world of dormant peerages, of murderous baronets, and ladies of title addicted to the study of toxicology, of gipsies and brigand-chiefs, men with masks and women with daggers, of stolen children, withered hags, heartless gamesters, nefarious roués, foreign princesses, Jesuit fathers, gravediggers, resurrection-men, lunatics and ghosts.” They contained grisly tales of murder, crime, and the supernatural, with the occasional romance thrown in for good measure. Between their first emergence in the 1830s to their decline in the 1890s, penny dreadfuls fascinated, horrified, and titillated millions.

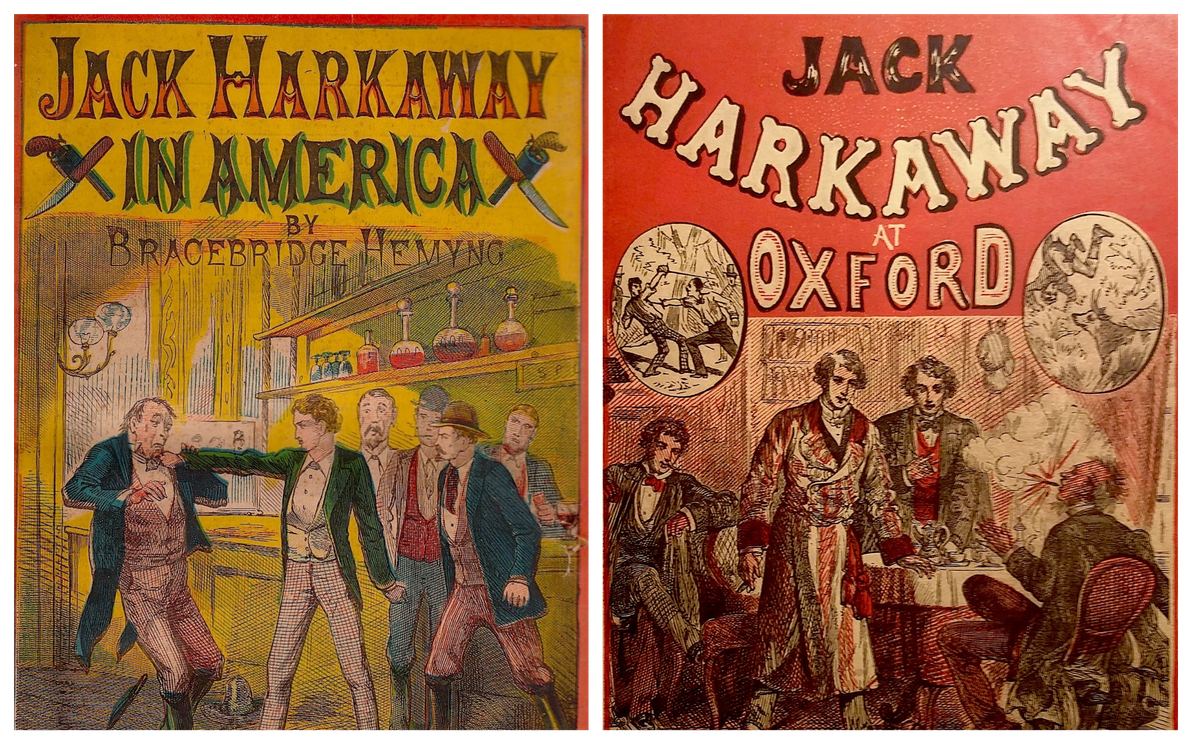

As one might expect, no audience was drawn into the world of penny dreadfuls more than children and teenagers. In fact, they specifically targeted young readers. Many of the stories feature young characters, such as the schoolboy Jack Harkaway, who would become as beloved to Victorian readers as Harry Potter is today, according to the British Library. Boys of England, a periodical marketed to young boys, first introduced the character in the 1871 penny dreadful “Jack Harkaway’s Schooldays,” which details the protagonist running away from school, boarding a ship, and embarking on a life of adventure and travel. Jack even had to battle a 15-foot python when one of his many pranks went awry.

The popularity of penny dreadfuls had another side: They helped to promote literacy, especially among younger readers, at a time when, for many children, formal education was nonexistent or, well, Dickensian. The proliferation of such cheap reading material created “an incentive to require literacy,” says professor Jonathan Rose, author of The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes. People were invested in the stories of Jack Harkaway and Sweeney Todd, and there was only one good way to keep up—learn to read.

While some historians credit compulsory education for the increased literacy of the age, “The fact is that most of the increase in literacy happened before you got universal free education,” says Rose. In England, education wasn’t required for all children until 1880, decades into the heyday of penny dreadfuls.

But don’t take our word for it. For London hatmaker Frederick Willis, reading penny dreadfuls while growing up eventually led to him picking up Shakespeare and Chaucer. “It was the beloved ‘bloods’ that first stimulated my love of reading,” he wrote in 101 Jubilee Road: A Book of London Yesterdays. Alfred Cox, an ironworker’s son, wrote in Among the Doctors that his “budding love of literature” started with “an enthusiastic reading of penny dreadfuls.” Even Welsh poet W.H. Davies grew up reading “the common penny novel of the worst type.”

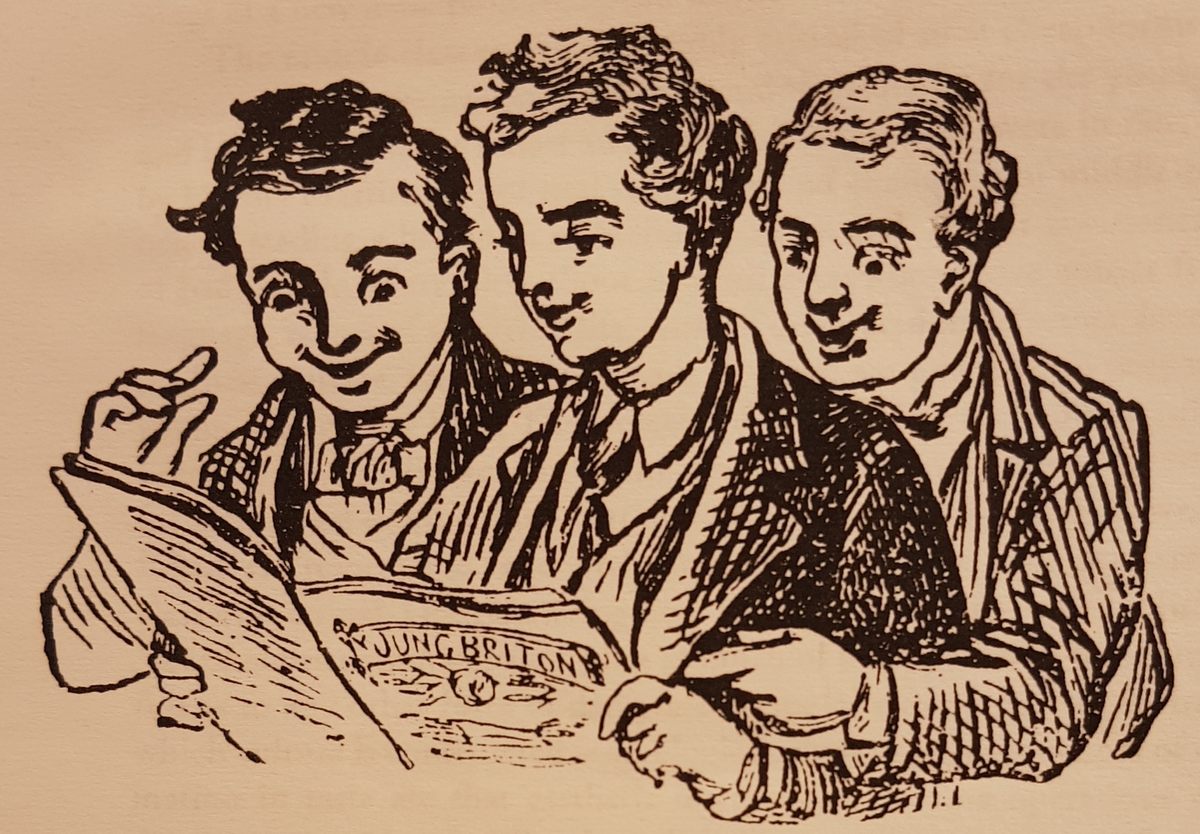

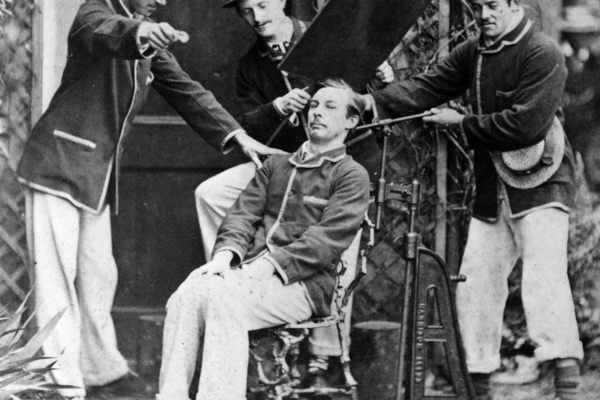

The serialized fiction was so popular among children that they formed clubs to share and read aloud the latest installments. Marie Léger-St-Jean, an independent scholar behind the penny fiction database Price One Penny, says that one group of factory girls in the north of England would pool their money together to buy the latest penny fiction before passing it around. Journalist Henry Mayhew’s 1851 book London Labour and the London Poor also “includes an account of people having a penny blood [another type of penny fiction] read out to a large group of people,” says Léger-St-Jean.

These clubs were “very common,” says Rose. “We’re talking about young people who have very limited disposable income. So, yes, they would basically meet, they would exchange these books. Some of them of course were illiterate so they would sit and be read aloud to.” As the century progressed though, reading penny dreadfuls aloud became less and less common—“because there were higher and higher rates of literacy,” says Rose.

Child labor was a common facet of working class Victorian society, and also has a place in explaining the appeal of penny fiction. In early-19th-century industrial Britain, the average age at which people started work was eight-and-a-half. Industries such as mining, chimney sweeping, and textile production sought out children to do specific tasks that relied on their small size, tasks that were often dangerous. The monotony of factory work was, at the very least, extremely boring. “If you’re in a working-class home, you’re going to the same factory job and doing it day-in and day-out. It’s just not a lot of variety,” says Rose. “And suddenly you have this kind of literature, that’s so different from what you read in Sunday school, and in that sense it’s escapism.”

But not everyone was happy about penny dreadfuls targeting young readers. Some suspected they were learning about more than how to read. “There was this sense that the working class were reading trash,” says Léger-St-Jean. In his book Leaves from a Prison Diary: Or, Lectures to a “Solitary” Audience, 19th-century journalist Michael Davitt referred to penny dreadfuls as “the pestilent literature of rascaldom which has educated so many criminal characters in this country.” An acquaintance who read these dreadfuls, he wrote, “ultimately became a noted burglar.”

Even if penny dreadfuls created a burglar or two, the reality is that violent crime actually decreased throughout the 19th century, says Rose. “You could absorb this literature and still be a very law-abiding and nonviolent person.”

The moral panic inspired by penny dreadfuls in the 19th century wasn’t all that different from the moral panics we’ve seen in more recent years: heavy metal, Dungeons & Dragons, video games, and, yes, Harry Potter. “We had the same worries about the comic books in the 20th century and rap music in the 21st century,” says Rose. “Adolescents naturally, you might even say it’s a healthy attitude, like to read stuff their parents don’t like.” From Hunger Games to Call of Duty, young people dig the subversive and transgressive. For Rose, it’s an “eternal phenomenon of adolescents.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook