What Do You Do With Hundreds of Unearthed Human Bones?

When a Philadelphia construction company dug up an old cemetery, local archaeologists stepped in to help—because there was no one else.

This past March, Anna Dhody got a phone call that put her day in ruins.

Dhody is a forensic anthropologist and the curator of the Mütter Museum, Philadelphia’s famed collection of anatomical curios. On the line was a contractor who’d spent the day digging the foundation for what will eventually become a 10-story apartment building at 218 Arch Street, a few blocks from the Delaware River. An earlier prediction of Dhody’s had come true, the caller told her—as they excavated, they had, indeed, run into more bones. How many? “A lot more,” said the voice on the other end.

Dhody and her friend Kimberlee Moran, the director of forensics at Rutgers-Camden University, had already helped these particular contractors deal with a box of bones they had found a few months earlier. Figuring they could easily reprise this roll, the two headed on over. “It wasn’t until we got there that we realized what ‘a lot more’ meant,” Dhody says. “[We found] coffins four-deep. It was very daunting.”

With the help of volunteer archaeologists from up and down the U.S. East Coast—as well as the contractors and their handy cranes—Dhody and Moran spent the next few days turning the construction site into an archaeological dig. All told, they ended up with 77 colonial-era coffins, each stuffed with bones and dirt.

Cities like Philadelphia have long, layered lives—which means they’re full of hidden surprises, including bones. “I sometimes say if you put a shovel in the ground, you should expect to find a human skeleton,” Janet Monge of the Penn Museum told Billy Penn last month. Over the past decade, construction projects in Philadelphia have unearthed centuries-old bottles, ceramics, and even an entire 18th-century city block. Experts say they’re shocked that more remains haven’t turned up.

While some of these finds enjoy automatic legal protections—for example, those found on public lands, or during projects undertaken with public money—others do not. The only relevant piece of Pennsylvania legislation, the Historic Burial Grounds Preservation Act, “is not constructed to address private activities on privately owned burial places,” says Howard Pollman, a spokesman for the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, the Commonwealth’s official history agency. “There is no path for PHMC to intervene even in this extremely negative situation.”

The plot at 218 Arch Street lies within a mile-square area known as Old City, which once housed the state’s original settlers. The neighborhood played an outsize role in America’s founding: the Declaration of Independence was signed in Old City, as was the U.S. Constitution. The future apartment building at 218 Arch will stand on a piece of land that, for much of the 18th and 19th centuries, was the site of the city’s First Baptist Church. The church originally housed a burial ground for parishioners. In 1860, as the city’s real estate priorities changed, this graveyard was moved to Mount Moriah Cemetery, farther southwest.

“Removed the remains of the Dead from our Burial Ground 2nd below Arch Street and reinterred them in our new ground at Mount Moriah Cemetery,” Assistant Treasurer B.R. Loxley wrote at the time, in the church’s register. “Superintended the work myself.”

That Loxley missed a spot (or 77) is somewhat unsurprising. In the past, people often moved graves without realizing just how many bodies were beneath them, says Dhody. It’s also possible that those buried had died of a disease their still-living brethren balked at exhuming—“this population lived through, or maybe didn’t live through, some very significant public health issues,” including yellow fever and cholera outbreaks, she says—or that their relatives couldn’t afford the posthumous moving costs.

When the remaining remains resurfaced this past fall—250 years later—those called upon to make decisions about the bones once again played hot potato. “Other governing agencies that would normally take over said ‘We have no jurisdiction here,’” says Dhody. Investigating the September find, Stephan Salisbury of Philly.com reported that three different city and state departments, as well as the Mayor’s office, were unable to take charge. The construction site manager says that the city simply told him to “rebury the bones” at the end of the excavation.

In other historically minded places, critics say, this doesn’t happen. If you find bones in many states—and a coroner or a medical examiner confirms that they’re old—a State Archaeologist will come by, investigate the site, and tell you what to do next. Some cities, including Boston, employ archaeologists of their own. (Philadelphia used to, but hasn’t since the 1980s. In the U.K., each county has its own archaeologist.)

Others have go-to companies that private contractors can hire to handle old remains. In Cincinnati, a firm called Gray & Pape successfully studied and re-interred several skeletons found during 2016 renovations of the city’s Music Hall. In New York, the firm Chrysalis handles a lot of such finds, including crypts unearthed under Washington Square Park in 2015.

Philadelphia archaeologists fear that their city’s bones and artifacts are suffering more inglorious fates. In a recent Philly.com article, some remembered amateur collectors pillaging a construction site for old bottles. When important historical discoveries are handled properly—as with that buried 18th-century block—it’s because the federal government steps in, they say. “In the past, entire graveyards have been bulldozed into the foundations of buildings,” says Dhody.

What Philadelphia does have is citizens who care, like Dhody and Moran, who did the best they could with a tough situation. After the surprise spring finding, “We had to really mobilize an emergency excavation project,” says Dhody. Because PMC Construction Group was waiting to get on with their project, the timeline was tight, making for a bare-bones dig—which, in archaeology terms, actually means that the bones stay covered. “Each coffin was excavated out in total, as a complete coffin, filled with dirt and remains,” says Dhody. The careful, step-by-step documentation that normally accompanies a job like this was impossible.

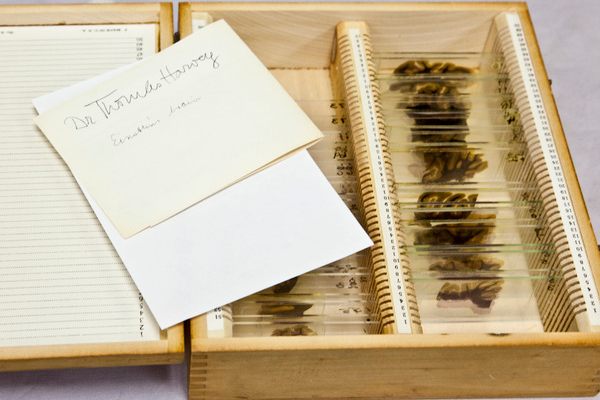

This means there’s a lot of work ahead—work that Dhody and Moran hope to repurpose as a learning opportunity, both for archaeology students and the local and national community. Right now, the bones are spread out over three different storage spaces. Money is needed to move them to a better facility, and bring in experts to study everything from the structure of the coffins to the stresses on the bones.

If all goes well, “each of [the coffins will be] excavated out, as a mini-excavation,” and results will be shared with the public on an ongoing basis, says Dhody. The Mütter Institute, the museum’s research arm, is currently crowdfunding to support these efforts. After they’ve learned everything they can, they plan to re-inter the bones at Mount Moriah, with financial help from PMC Construction Group.

Dhody hopes that this will serve as a learning opportunity for the city, too. “If we hadn’t stepped in, the best case scenario [is] the remains would have been bulldozed into bags, and put in storage somewhere until someone figured out what to do with them,” says Dhody. Archaeologists fear that Philadelphia’s current public park revitalization initiative will result in a whole lot more skeletons coming up. “I’m hoping this will also spur legislators to put something on the books,” Dhody says.

In the meantime, she’s focused on doing what she can with what she has—namely, 77 coffins chock full of history. “Something like this only comes across an anthropologist’s trowel once in a lifetime,” she says. “We’re lucky.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook