The Duo Who Documented the Birth of NYC’s Subway

For brothers Pierre and Granville Pullis, photographing the sprawling system was intrepid, precise work—not unlike the construction itself.

Pierre Pullis had a photography studio on Fulton Street, in New York City, but he spent a lot of time working outside its walls. For about four decades in the first half of the 20th century, he lugged his camera to some rather inconvenient places around the city—including beneath its boulevards.

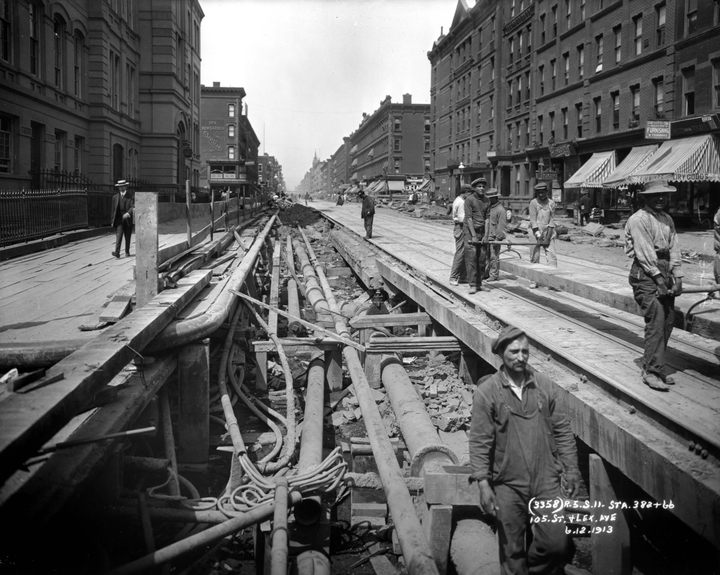

His photos “are as interesting as they are difficult to obtain,” the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported in 1901, soon after Pullis undertook his work. “In many cases, Mr. Pullis and his assistants are obliged to place their cameras in perilous positions in order to photograph the face of a rock or the effect of a blast, and taking flashlight pictures knee deep in a twenty-five foot sewer.”

Pullis was an early photographer of subway construction, tapped by the agencies responsible for building the first underground rapid transit line in NYC. Along with his slightly younger brother, Granville, Pierre took tens of thousands of photographs of stations, equipment, construction sites, and the people who built the stations, as well as the pedestrians who would eventually wedge themselves onto the trains.

Portions of the brothers’ vast archive were on display at the New York Transit Museum in 2021. But the survey captures only a sliver of the museum’s holdings of the Pullises’ prints, glass negatives, and film negatives.

“[W]e could do a show of an equivalent size three times a year for the next 10 years and still not show all of them,” says associate curator Jodi Shapiro, who organized the exhibition. “It’s the collection that keeps on giving.”

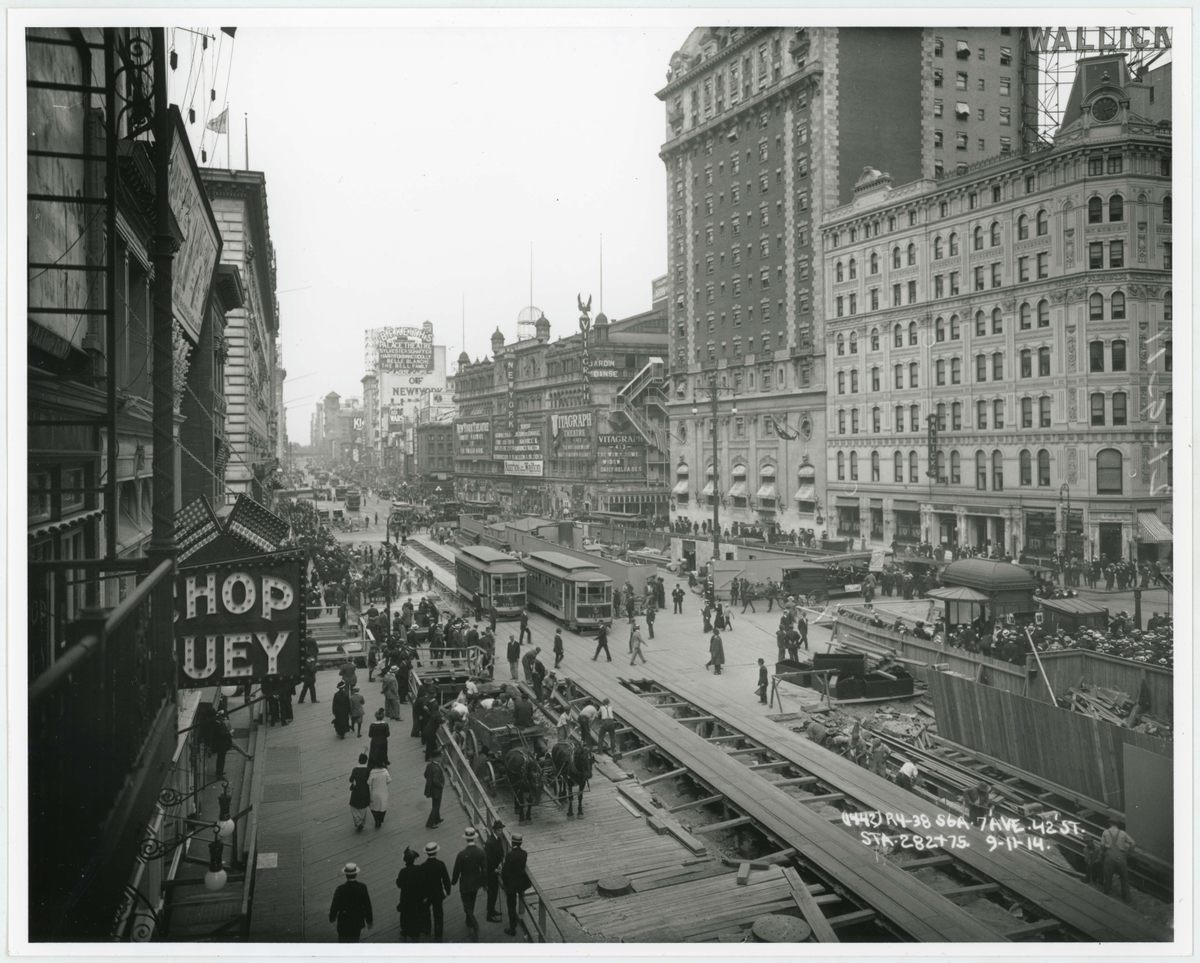

The Pullises worked methodically, often revisiting a site several times to keep tabs on its progress, and to inventory how the world was changing, both above ground and below it. They kept careful records in a log book, where they noted the day, location, land use, and other pertinent details. Sometimes they’d walk down a block and stop to take a photograph every 10 or 15 feet. “Especially when construction was in full swing, they’d go back several times within a couple of months,” Shapiro says. Other times they’d return to a building to document it in different states, before and after excavations carved out the ground below.

The project stretched on for years, as Pierre worked through the 1930s (he died in 1942), and Granville photographed until at least 1939. (As the system continued to expand, so did the ranks of photographers, Shapiro says. Because there was so much construction going on, the agency couldn’t reasonably expect one person—or even two—to cover it all.) Along the way, the Pullises and amassed a deep and rich record of what Shapiro calls the “nuts and bolts of subway construction”—an extensive overview of “how the sausage gets made, as it were.”

The brothers’ images are technically proficient, but also artistic and tenderly humane. Many of the photographs were bound into books—some in the museum’s collection still have holes punched through one end—as reference documents, or as evidence that could be called forth in the event of a lawsuit (it was, after all, an era when construction was staggeringly dangerous and injuries were commonplace).

They were also impeccably timed snapshots of urban life and work. Pierre and Granville captured signs and businesses and moments of striking symmetry, such as people frozen in mid-stride as they wandered between buildings. “What makes these full of personality [in a way] that other photographs of this type usually [aren’t] is that you can tell both of [the photographers] waited for just the right moment to click the shutter,” says Shapiro.

Pierre and Granville frequently framed workers in the foreground, showing compassion for the people sweating and straining to build the city’s sunken arteries. The workmen, in turn, appear comfortable in front of the camera, as if they’ve just cracked a joke with the person behind the lens.

“A lot of the people in these photographs, we’ll never know their names,” says Shapiro. “But we know their faces. That’s our privilege—to let people know, these are the people that built this. Somebody photographed them and cared enough about them to make them look dignified in their work.”

Pierre and Granville are slightly less anonymous than the unnamed workers in the photographs, but Shapiro says she and her collaborators at the museum are keen to learn more about the duo. “One of the underlying sinister reasons we’re having this show is that we’re hoping … someone who’s related to them will come out of the woodwork,” she says, laughing.

The team scoured old newspapers and other documents, but didn’t find much about the brothers’ lives. With the exception of some court records from when they were called as witnesses, there are very few accounts of Pierre or Granville speaking in their own voices. “I just hope that someone out there knows about them,” Shapiro says. “The archivists and I were like, ‘Somebody—there’s got to be somebody.’”

Shapiro can’t go back in time and talk to the Pullises, of course, or to the men they depicted working below the streets. But if you visit the exhibit, study the subjects’ faces. Then, the next time you’re in the subway, try to remember their work—and the men who photographed it.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook